by Corry Shores

[Search Blog Here. Index-tags are found on the bottom of the left column.]

[Central Entry Directory]

[Corry Shores, Entry Directory]

[Deleuze, Entry Directory]

[Other entries in this Rhythm of Sensation series]

Deleuze speaks of modulations in two general senses: 1) as alterations of modalities that 2) sometimes proceeds through modules which affect those modalities. Deleuze’s references to Paul Cézanne and Richard Pinhas direct us to the examples of color modulation in Cézanne’s painting, to musical modulation in Wagner’s compositions, and to electronic sound synthesizers.

Deleuze notes that Cézanne’s modulation of color, his “principle operation,” suppresses contrasts of light and darkness.[1] It creates relief through changes of hue, and not of tone. (Colors, such as red and green, are hues, and their tonal values are the degrees of lightness or darkness, shifting chromatically from white to black). Through these changes, modulation serves as a “variable and continuous mold” that alters color, doing so by the law of Analogy:[2] this law for Cézanne is his logic of organized sensation, which we will explain first before addressing his use of color modulation.

Cézanne distinguishes representation from reproduction: a painter may only represent the sun’s intensity, he cannot make the paint shine so brightly.[3] However, the artist can surround the depiction of the sun with an arrangement of other colors organized in such a way that they invoke in us the sensation of seeing the sun. The painter, then, is not to copy the object, but to realize the sensations we have when viewing such an object, which requires that the painter break from a visually accurate rendition, and paint instead according to a “logic of organized sensations:” when Cézanne views his scene, his eyes move slowly from place-to-place. With each subtle movement, he does not so much intend to reproduce exactly what he sees; instead, he selects a color which would invoke in his viewers the same internal states that he has while viewing that part of the scenery. However, any single selected color alone does not by itself produce that internal state. Rather, it is only in its relation to its immediate surrounding colors that it can have its unique effect. Hence in this way, Cézanne modulates the color, because he makes subtle and intentional variations on the local level, so that his viewers undergo sequences of modulated internal states resembling the ones he experienced while painting.

Thus, the colors he selects serve as a sort of coding of sensation that the viewer ‘interprets,’ but not as though they were symbols.[4] However, the interpretive process is just as much cerebral as sensual, hence its “logic.”[5] Painting, for Cézanne, involves more than mere sense impressions and instant associations: it also requires his conscious effort to select the right combinations of color alterations. Cézanne often used broad, ‘blocky’ paint strokes, carefully placing one patch at a time, progressing from one part of the painted object to the next, following color sequences that would be interpreted by the viewer so as to reproduce the experience of the painted scene or object. Hence his “vision was much more in his brain than in his eye.”[6]

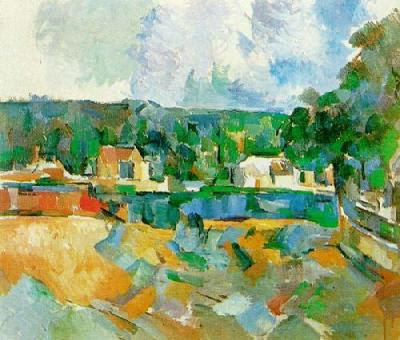

[Note below the 'blocky' strokes in his Mont-Sainte Victoire. See also the close-up]

(Thanks dbeveridge.web.wesleyan.edu)

Deleuze explains that Cézanne creates depth by replacing the traditional use of value differences with his particular brand of color modulations.[7] Normally, depth is portrayed through modeling: the painter uses differences in value (lightness and darkness) to express the physical relief of the model being depicted.[8] Adding white or black to a color diminishes its intensity, which as a painting term means the degree of saturation or purity of color tone. When there are no contaminating inclusions of black or white to a color, it is in its purest hue, which means it is at its highest saturation and its greatest intensity (in this restricted painting sense of the term). In modeling, one would use variations in value to show relief: changing the amounts of shading indicates the positions of objects in reference to a light source, and creates the visual dimension of depth. Cézanne, however, uses the oppositions of warm and cool tones, in some cases, to represent light and shadow or varying distances of objects.[9] Blue has no greater tone value than yellow when both are equally saturated, yet in certain contexts, when blue is painted next to yellow, it might suggest depth or volume.[10] To modulate the color would be for Cézanne to place a patch of one saturated color beside another, with their relation bringing about an effect determined not by some pre-set system but by the circumstances of their contextualization with the other color patches. (We can see in this Cézanne landscape below how the intense green on the horizon’s center recedes into the background. What is notable about this is that normally darkened colors seem like shadows and appear as though at a distance. Here we see that the intense green has not been darkened, and yet it colors the most distant place on the horizon).

Hence, in Cézanne's paintings we often encounter seemingly out-of-place color strokes, or unrepresentative combinations of color. In his portrait below of Hortense Fiquet, for example, we see odd color-blocks used for her skin, (painting is cropped for focus).

(Thanks www.dl.ket.org)

However, if we attended more to the sensuous and conceptual affects that these colors have on us, we might better detect the logic of organized sensation at work in his paintings. Lawrence Gowing explains how Cézanne’s “mutations of color” were as theoretical as they were perceptual:

When one of his visitors was puzzled to find him painting a gray wall green, he explained that a sense of color was developed not only by work but by reasoning. In fact the need was both emotional and intellectual. The mutations of color with which he modulated surfaces that would have seemed to a less logical mind to require no modeling whatever were a necessity to him. [11]

We may illustrate with the example of Cézanne's The Green Pitcher.

According to Lawrence Gowing, Cézanne began with a blank center-point of the pitcher, the point culminant, which is the part of the object which is closest to our eyes.[12] He then surrounds the culminating point with blue color-patches, and proceeds by running through the color spectrum to green (indicating the actual color of the pot) then to yellow, according to a pre-conceived ‘logic,’ in order to evoke the sensations of seeing the pitcher.[13] Norman Turner disagrees with Gowing’s claim that the color order was fixed in advance, a point which will prove relevant when describing Bacon’s continuously variative modulation. Turner argues that Cézanne does not select his colors according to an overarching and pre-determined organization, but rather he continues to each neighboring color-patch on the basis of how its immediate predecessor conditions that color change; for, each subtle transition alters the possibilities and limitations for how he may proceed. In other words, Cézanne was not so much concerned with how one color-patch associates with another one far away on the canvass, but rather more with the relation between any one patch and its immediate neighbor, in terms of the sensations unlocked in a transition from one to the other.[14] This influences the subtle sequence of quick impressions we have when our eyes move from one part of the painting to the next.

Also, to better grasp Deleuze's notion of continuous modulation, we might follow Turner and Richard Pinhas, Deleuze's student, by comparing Cézanne's color modulation to Wagner’s key modulation. Each time Cézanne modulates to the next color, he creates a general feeling, and opens possibilities for the next transition, which might not have been available for a different color. In this way, Cézanne's modulation is thought to be like musical key modulation.[15]

[We can explain the musical technique of modulation by drawing from the work of ancient Greek philosophers. Pythagoras demonstrated harmony relations between sound frequencies, by using single-stringed instruments called monochords.

(Thanks alchemywebsite.com)

(Thanks www.britannica.com)

For example, he demonstrated that when one string is played simultaneously with another one that is half its length, the strongest harmony is produced: this is the octave harmony. Pythagoras divided the octave into 12 smaller units, because this particular division establishes pitches with the greatest possibilities for harmonic combinations.[16] If one were to compose a song using not all twelve pitches, but instead a smaller pre-determined set, then certain harmonic relations would be excluded, and others emphasized. Different such limited sets, then, have their own feel or color to them, their own mood. Some such early Greek note patterns are called moods or modes; and both Plato and Aristotle make reference to the different sorts of emotions that these modes evoke. Both philosophers, for example, criticize the mixed Lydian (mixolydian) mode for darkening people’s moods.[17] However, one can also change from one mood to another, that is, to modulate between modes.

Yet, there is a more subtle sort of modulation which we refer-to here, key modulation: of the many Greek modes, two became especially prevalent, but each of these may itself slightly vary its feeling; the note patterns may change their initial “root” note, which makes more subtle changes of mood. These different patterns are the keys, which can be modulated by using notes at the end of one melody (cadences) which are found in both keys, so to make a smoother transition.] Such modulating changes the key-feeling, but in a way which couples different moods at once during the transition. Likewise in painting, the artist may select certain dominating hues, which together have their own key-feeling, if you will, and modulate between them (the use of music terminology in describing painting is common, for example, rhythm, tone, harmony, dissonance; and vice versa: texture, color). The effect of Cézanne's color patches has little to do with the representation of their objects; rather, “it is the relationships between them – relationships of affinity and contrast, the progression of it tone to tone in a color scale, and the modulations of it scale to scale – that parallel the apprehension of the world.”[18] This is Deleuze’s philosophical interest in this sort of modulation, because he would like to explain how Bacon’s diagramming couples Figures’ movements by modulating the colors between them.

A description of Wagner’s modulation techniques is important for this discussion, because he advanced modulation from a more rigid sort to a smoother one, to a modulation synthétique continue, as Pinhas calls it; and, it is this latter sort that concerns Deleuze. [In key modulation before Wagner, a sense for the original tonal point of departure is maintained, so that the modulations may return to it for resolution. Usually in these cases, the composer uses a convenient bridging chord whose notes are found in both the prior and the latter keys, along with ambiguous notes, to serve to smoothly transition from one key to another. We might illustrate with an example in which the words in a verse serve to make this bridging transition. Wagner compares two possible lines: 1) Liebe gibt Lust zum Leben, (love gives joy to living) and, 2) die Liebe bringt Lust und Leid, (love brings joy and sorrow). In both cases, the phonetic compatibility of the substantives groups them together, superposing them through rhyme, despite their distinct occurrences. In the first case, the feelings evoked by the terms Liebe (love), Lust (joy), and Leben (living) are all compatible, just as are the phonetics of their terms. However, in the second case, the final term Leid (sorrow) ends the phrase with a sadder tone, but is still phonetically superposed to the happier feelings preceding it and overlapping it through phonetic harmony. Hence in the second line, a musician composing the music to such words would have cause and means to move to a new key feeling, perhaps a more somber minor key, and the transition can be made because the phonetics serve to bridge the two different key feelings. In the case of his Tristan und Isolde, his composition technique gives the feeling of moving continually towards other key feelings, although without ever arriving to one, and he leaves many of the chords ambiguous as to their key. His purpose is to induce the feeling of unsatisfied desire, and does so by creating expectations for resolution by modulation into another key, but yet disappoints that expectation by leaving the keys in limbo.][19] Hence in this way, Wagner advanced the technique of modulation, so that instead of limiting developmental options by striving to give the listener a sense of orientation and resolution, Wagner’s modulations progress more freely by lacking a determinate ground and finality.

A student of Deleuze, Richard Pinhas, a progressive musician and philosophy scholar, further elaborates the importance of Wagner’s innovation of the modulation synthétique continue, which led to 20th century developments in modulation, including the electronic modulation of synthesizers. [Pinhas explains that Wagner’s key-modulation technique allows for the continuous translation of melodies into other modulated forms, thus serving as an opérateur d’hétérogènes: something that couples a series of heterogeneous elements one-after-another.[20] Because Wagner’s modulations in some works never obtain a feeling of resolution, none of the modulated keys took a dominant role, and they all smeared into one continuous modulation. Younger contemporary of Wagner, Debussy, pushes modulation even further in this direction. In Wagner, we can follow the tonal progressions and tensions, even though they never resolve. Debussy, however, does not have this tonal tension, and his modulation is not even the tension of wandering unresolved key feelings; but rather, it remains within the sensuousness of one chord (one small group of pitches), which are gradually built up with more instruments playing the notes of that chord. This produces the aquatic effect: it modulates not between keys, but instead is a fluid modulation with very smooth transitions between different parts, which blurs the boundaries between them. Using this technique, Debussy continuously modulates other features of the sound, like timbre, in a modulation synthétique continue.[21] Yet this watery blurring does more to deform the sounds, to smear one into another blurry one. This function has been recently taken-over by electronic synthesizers, both digital and analog. They alter sounds, but always by degradation, taking away their fidelity from their parent sound, making them low-fi(delity), deforming the sound in a sort of perpétuelle transition.[22]] This modulatory technique of Wagner, Debussy, and electronic synthesizers operates as a diagramme modulaire, bringing about la modulation comme différence pure;[23] Deleuze is interested of course in these differences that are forced together through modulation, which likewise disorganize our faculties.

Wagner’s innovations, then, resemble the color modulation in Cézanne’s logic of organized sensations. Cézanne moves locally from one color patch to the next, without necessarily maintaining an orienting color base, moving rather through a continuous modulation from one patch to the next. Deleuze elaborates this notion of a continuous and aimless modulation, by differentiating the operations of analog and digital synthesizers, basing his distinction on an unpublished text by Pinhas.

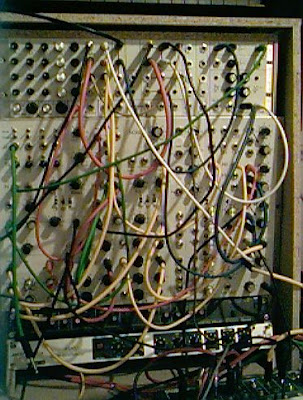

[Deleuze notes that analogical synthesizers operate by sending the sound signal through different modules, which are discrete self-contained circuits. Each one alters the sound in its own unique way; and they may be linked and re-linked by “patch” cables, which allows for countless ways to route the sound signal through the different modules or patches.[24] (We can see Deleuze’s example in the image below of a modular analog synthesizer: features of the sound signal are modulated when sending it through different modules by means of the patch wires, with uncountable possible outcomes).

Digital synthesizers, Deleuze explains, are integral, that is to say, rather than the signal moving through a sequence of modules, it is instead processed by electrical circuitry whose different parts are already integrated with each other, and do not require manual connection with wires.

We see in the image above that the parts of a digital synthesizer’s integrated circuit are already wired together; the signal’s processing happens on a more “abstract” level through the manipulation of code.] The analog modules parallel Cézanne's use of “color patches” to modulate color: he begins with one broad stroke of uniform color, then moves to the place beside it, changing the color somewhat, thereby modulating its hue; and, he decides which change to make according the logic of organized sensations. Thus Cézanne, Wagner, and electric synthesizers are modulatory in two ways: by modulating the features of the sound or color, and doing so through a series of modules (color-patches, keys, synthesizer-patches).

Because each patch of an analog synthesizer has circuitry components that reduce properties of the sound signal itself (according to Deleuze), analog synthesizers modulate by means of subtraction, and in this way some of the fidelity to the original sound is lost. In contrast, digital synthesizers are additive, and Deleuze makes this distinction clearer by comparing the operations of pass filters; and, although this may be one of his most technical examples, it serves to explain how we are to give a positive connotation to deformation. [We might imagine a musician playing on a drum kit, using both deep drums and cymbals. The drums produce low frequencies, and the cymbals high ones. A low-pass filter, whether analog or digital, will let the sound of the drums through, and strip away the sound of the cymbals, because a low-pass filter only lets the low frequencies pass through it. In the specific case of low-pass digital filters, the sound waves produced by the drums and cymbals are converted electronically into a code; and, in order to modify it, the digital filter must perform operations on the code. This process makes the original code more complex by adding new coded information to it, even though this new larger and more complex code will then decode into a diminished sound: when we play the output of the digital low-pass filter, we hear the drums perfectly, but the cymbals not at all. For analog low-pass filters, the sound waves of the drums and cymbals are converted into an electrical signal. Both the original sound waves and the converted electrical current oscillate in concord (they together move back-and-forth at the same frequencies): this is analogical mimicry. The analog low-pass filter, then, only lets the electrical signal through when it is moving at low frequencies, and blocks its passage when moving at higher frequencies. This results in a diminished signal, that when re-played, reproduces the sound waves for the drums, but not for the cymbals.][25] What Deleuze concludes from this distinction is that an analogical process of sound modification (modulation) enhances a sound by subtracting something from it. Whether or not that is an accurate depiction, is beside the philosophical point that this example illustrates. Deleuze calls analogical modulation an intensive subtraction, because he considers intensity at its greatest magnitude to equal a value of 0; and hence, its increases in intensity are actually falls to 0.[26] (Of course, Deleuze's statement that there is no absolute 0, which we cited previously, refers to the intensities studied in physics – for example, temperature – and perhaps has no bearing on facultative intensities). Yet, to better grasp this notion of intensity equaling zero, we will need to explore his concepts implication and explication.

Deleuze's account of implication and explication in Difference & Repetition will seem abstract unless we apply these terms to his revised doctrine of the faculties. In those cases when our faculties are disordered, we would be wrong to think that the differences between them can be measured, as if there were a homogeneous scale of values that could be used to gauge their distance from one another. However, we might still say that to greater intensities corresponds more depth: as our faculties become more disorganized, it is as though we loose stable ground and feel ourselves in freefall. However, if our faculties were to come more into accord, stability would return, and objects would become more recognizable, as we become more able to determine their spatiotemporal features. In this way, the heterogeneous intensive rhythm of sensation is made more homogeneous and extensive, and thereby, more qualitative features may be attributed to the sensed object. Yet by doing so, the original intensity diminishes, as it comes to take the form of extensity and quality.

Thus, Deleuze speaks of intensity as being implicated and inexplicable.[27] From what we have said regarding the discord of the faculties, it might seem that intensity resides implicitly in facultative disorder, and is only transcendentally sensed as the differences between faculties. We might illustrate this by considering Bacon’s 1946 Painting.

After a period of initial confusion regarding the meaning and coherence of the images, we might imagine instead that we eventually somehow become able to determine the “story” that it tells. We could then view the painting in its full extent, and explicate its meaning, its qualitative & extensive features, and its identity. When we were initially confused by the painting, we experienced the coupling of contraries that make up its matters of fact; yet, by explicating these phenomenal paradoxes into coherent descriptions, we cease to experience the painting as an event, and walk-away retaining a dull representation of it.

Thus, explication cancels intensive difference insofar as it becomes explicated. Such differences in extensive features as “the high and the low, the right and the left, the figure and the ground” flow from something deeper, in fact, from the intensive depth itself. In other words, before we are able to discern the extensive relations in our perceptions, our faculties must first be confused by the irregular ways that things are given to our senses (this is the rhythm of sensation). As our faculties establish artificial regularities – by finding a common measure to determine the extensive features of the things we perceive – what was once intensive depth then becomes extensive visual distances. It is by this means that we come to discern the ground from the figure it surrounds.[28] This will be important in contrasting Bacon’s modulation with Cézanne's; for, by merging figure and ground onto a common plane, Bacon better keeps depth from explicating into extensity.

Depth, then, is the magnitude of the faculties’ disorder.[29] Moreover, Deleuze does not consider the distances in depth to be a negative relation, but rather a positive affirmation of the difference making-up the distant faculties. He offers a mathematical example of how distance can be used to positively affirm the value of a number. He first considers a formulation that defines equal mathematical values negatively; for, it claims that, if two values cannot be different, then they must be the same. (More accurately, ‘if a ≠ b is impossible, then a = b’). Thus, the sameness of value between a and b can be established by denying the possibility of their difference. Contrariwise, his second formulation positively establishes the sameness of two unknown values by affirming that they both share the same distances to other values. (‘If a is distant from every number c which is distant from b, then a equals b’). Although, in Deleuze's case, he is not speaking of an extensive quantitative distance value, but an intensive one which cannot be given an explicit value-measure.[30] For him, the notion of equality is a matter of extensity, and quality is an issue of resemblance. However, “extensity and quality ... cover or explicate intensity. It is underneath quality and within extensity that Intensity appears upside down,” (C’est sous la qualité, c’est dans l’étendue que l’intensité apparaît la tête en bas).[31] Hence in its depth, intensive difference is not negative, but only appears to be so when explicated.

The intensive differences between disorganized faculties precede all sensations of extension and quality, but yet none of our given empirical faculties can sense this intensity. The role of the faculties is to explicate the objects they commonly detect; thus, they cannot sense intensity; for, in order to do so, they would need to raise it from the depths, elevating it to the “surface” of extensions, thereby canceling it before they can sense it. When extensities explicate intensities, the intensities become concealed. Thus, intensity can only be detected by a “transcendental exercise of sensibility,”[32] in which our faculties allow themselves to be pushed to their limits so to let the intensities flow through our bodies’ various zones and levels. Hence, the purpose of taking drugs for sensory distortion is to transcendentally sense intensity without any extensities or qualities that might explicate it, so to feel the irregular rhythm of sensational chaos. (Although it is not quite clear what Deleuze means by sensing something transcendentally, it seems that we may reference his descriptions of the way the BwO experiences its internal disorders).

Before we are able to explicate an object, we must first presume it is possible to do so. Kant explains this in terms of the object = x, which is a concept that Deleuze modifies. Kant explains that cognition is only possible by means of a concept, which enables us to unify our successive manifold of intuitions in just one act of consciousness.[33] Even in sublime experiences when these successive apprehensions could not be unified, still we presuppose the possibility for any object whatever to be unified into a concept. In other words, there is the a priori necessity that there be a sort of empty category or generic object to which any representation or concept could correspond; otherwise, the series of apprehensions would have no cause to unify. This generic object is the something in general = x, or object = x, which serves as the transcendental ground for “the unity of the consciousness in the synthesis of the manifold of all our intuitions, hence also of the concepts of objects in general.”[34] And, this original and transcendental condition is transcendental apperception, which is the “pure, original, unchanging consciousness;” whereas empirical apperceptions are the sequences of sense intuitions. Because the object = x is not empirically intuited, Kant considers it as the “transcendental object.”[35] Deleuze characterizes this something = x as a something = nothing, because it is an empty apperception. However, it becomes a lion = x when we synthesize all the particular empirical apperceptions that can turn the undetermined x into a lion: its “long hair in the wind, a roar in the air, a heavy step, a run of antelopes, well, I say it's a lion.” In this way, the diversity of empirical apperceptions becomesspecified and qualified when the faculties enter into accord regarding the series of apprehensions; and, when that synthesized image in the imagination is matched with the concept for lion, the perceived lion becomes recognized.[36]

As the a priori condition for the comprehension of empirical intuitions, the object = x is a matter of transcendental apperception; and, as non-empirical, it exemplifies Kant’s transcendental idealism. Deleuze adopts this notion of the transcendentality of the inexplicable something = x; yet, because for him it is not transcendentally “apperceived” in the mind – but rather is the underlying violent motivational force driving each empirical faculty to its limits in their effort to synchronize – the object = x exemplifies Deleuze’s transcendental empiricism.

Thus, we see that as intensity decreases, objects come more to be determined according to their extensive spatiotemporal and qualitative features, and in that way they become more explicated into extensity. Deleuze summarizes this inverse relationship with a modification of Kant’s formula, intensity = 0, which for Deleuze means that intensity is at its greatest magnitude when its numerical value is zero. However, Kant’s scale is the inverse of Deleuze's; for Kant, thenegation of intensity has the value of zero. Uncovering the difference between their formulations will explain how intensity is a fall for Deleuze, and thus why modulation produces this intensive drop.

For Kant, sensations have an intensive magnitude, which is the degree of influence on our senses, and it may diminish to 0.[37] As it rises-up from 0, its degree of intensity matches the extensive magnitudes of those objects causing its increase, so that an illuminated surface of some extensive measure causes as great a sensation as would the combination of a certain number of smaller such surfaces, themselves each of equal luminosity.[38] In other words, greater intensities correspond to greater extensities, which for Kant, provides a way to quantify them.

However, for Deleuze there is an inverse relationship between intensity’s magnitude and its measure: when its numerical measure is high, its actual magnitude (of facultative disorder) is low, and vice versa. Deleuze does not want us to take this formulation too literally, because we really have no way to quantify our intensities, not even inversely by assigning them higher numerical values. Rather, what he wants to emphasize is that the more our faculties disorganize, the more we are able to experience intensity without it being cancelled by extensive explication. This is his way to counter the Kantian notion of perception, because for Kant, when there is no phenomenal reality, intensity equals zero;[39] but for Deleuze, phenomena “appear” (flash) when intensity is at its greatest, which occurs when its numerical value equals 0; for, that happens when extensive numerical values are least a factor in sensation. Thus, we experience an increase of intensity as a fall to zero, and as a fall from stable ground.[40]

Hence, we may return finally to the falling intensive subtractions of modulation, which Deleuze exemplified with the analog synthesizer. We might also recall that, for Pinhas, electronic-synthesizer modulation causes sounds to become low-fi: by decreasing fidelity, we experience a sort of confusion as we come less to recognize the sound. Bacon’s diagramming acts as a modulator, then, in the ‘synthesizer’ sense of the term, because it is a scrambled distortion that bends an image into alternate dimensions and formations. Deleuze differentiates Bacon from Cézanne in terms of Bacon’s deformation of bodies, but also in terms of the depth these painters create. Cézanne's modulations – which use color alterations to create visual depth relations – cause in the viewer’s perception the sense that objects in the background are moving away, and those in the foreground are moving forward. (Below, in Cézanne's The Bathers, we see both a slight deformation of bodies; and, we may also notice how the modulation from the skin colors to the green causes the plants to recede into the background as the bodies seem to lift forward).

(Thanks www.dl.ket.org)

Bacon’s diagramming, on the other hand, superposes incompatible spatial dimensions so to confuse extensions of visual depth; and, the vast expanses surrounding the deformed figures are often a monochromatic flat background rather than a three-dimensional space fading-off into the horizon. Bacon’s visual depth, then, is more shallow and superficial in the sense of extensity, and thus deeper in the sense of intensive facultative depth.[41] (Below, in Bacon’s 1982 Studies of the Human Body, we see the flat expanse which places the background at the same level of depth as the figure).

(Thanks www.centrepompidou.fr)

Deleuze, then, differentiates Bacon’s and Cézanne's modulation techniques. When Cézanne modulates from one color patch to the next, he chooses each variation according to which color will replicate the experience of seeing the actual scene being painted, that is to say, according to alogic of organized sensation. Bacon’s technique, however, instead involves a logic of disorganized sensation: his diagrammed modulations are not determined rationally, but come-about through the irrational influence of chance. Also, Cézanne’s modulation would seem more like Wagner’s, where there is somewhat of a sense of key feeling for each color patch, even if they never resolve. Bacon, however, modulates color in a similar manner, yet for him, there is more deformation of bodies, which in terms of the colors in the diagrammed areas would mean something like the fidelity-lowering effect of continuous modular synthesis that Pinhas describes. Bacon’s diagram, then, deforms bodies through continuous modulation, as though it were a carnival mirror that not only altered the proportions of the figures, but their entire appearancesas well. So, by means of diagramming’s modulation, Bacon creates aesthetic analogies that force our faculties to try to organize while at the same time barring them from doing so. To witness Bacon’s paintings, it seems, would be to have an unresolving sublime experience.

Hence, we see that the importance of Bacon’s diagramming technique in Deleuze's thinking is that it exemplifies concretely the way that chaos and order interact so to produce fuller sensations, by means of the internal dissonance of our faculties and our disharmony with the world around us. It is in this way that Deleuze's theory of sensation runs counter to the phenomenological account of the organicism and harmony of perception.

[1] Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon: Logic of Sensation, Transl. Daniel W. Smith, (

[2] Logic of Sensation, p.83. Logique de la Sensation, p.111.

[3] Lawrence Gowing, “Cézanne: The Logic of Organized Sensations,” in Conversations with Cézanne, Ed. Michael Doran, (

[4] Gowing, p.197.

[5] Gowing, p.212.

[6] Norman Turner, “Cézanne, Wagner, Modulation,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, (Vol. 56, No. 4, Autumn, 1998), pp. 359. Quote from: Gowing, p.189.

[7] Deleuze, Logic of Sensation, p.83. Logique de la Sensation, p.111.

[8] “‘Look well at your model’ Couture advises, ‘and ask yourself where the light is greatest. ... Establish the point at which the shadow is deepest, the black most intense. It serves as a guide, as a standard for finding the different values, of your shadows and your tints,’” Turner, p.358.

[9] “One should not say model, one should say modulate” Cézanne, qtd. in Turner, p.360. “On ne devait pas dire modeler, on devrait dire moduler,” Turner, footnote 34, p.363.

[10] Gowing, p.191.

[11] Gowing, p.186.

[12] Joachim Gasquet, “What he told me...” in Conversations with Cézanne, p.121.

[13] Gowing, p.187.

[14] Turner, footnote 27, p.363.

[15] “Where it gives place to the juxtaposition of yellow and red and the alignment of the form appears to change, it may be that Cézanne thought of himself as passing to the next scale,” Gowing, p.204.

[16] Crotch, “On the Derivation of the Scale, Tuning, Temperament, the Monochord, &c,” The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol. 10, No. 224, (Oct. 1, 1861), p115.

[17] Plato, Republic, Book III, 398e. Aristotle, Politics, 1340a.

[18] Gowing, p.204.

[19] Turner, “Cézanne, Wagner, Modulation,” p.354.

[20] Richard Pinhas, “Le rythme et la modulation synthétique: Simultanéité et compossibilité des motive chez Richard Wagner,” in Les Larmes de Nietzsche: Deleuze et la musique, (

[21] Pinhas, p.171.

[22] Pinhas, p.176.

[23] Pinhas, p.180.

[24] Deleuze, Logic of Sensation, p.81. Logique de la Sensation, p.109.

[25] Logic of Sensation, p.81-82. Logique de la sensation, p.109-110.

[26] Logic of Sensation, p.82. Logique de la sensation, p.109-110.

[27] Difference & Repetition, p.228. Différence et répétition, p.293.

[28] Difference & Repetition, p.229-230. Différence et répétition, p.296.

[29] “The strangest alliance is formed between intensity and depth, which carries each faculty to its own limit and allows it to communicate only at the peak of its particular solitude,” Difference & Repetition, p.231. Différence et répétition, p.297-298.

[30] Deleuze, Gilles. Difference & Repetition. Transl. Paul Patton.

[31] Difference & Repetition, p.235. Différence et répétition, p.303.

[32] Difference & Repetition, p.236-237. Différence et répétition, p.304-305.

[33] Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, Transls. & Eds. Paul Guyer & Allen W. Wood, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), p.231, A103.

[34] Critique of Pure Reason, p.232 A106.

[35] Critique of Pure Reason, p.232, A107; p.233, A108-110.

[36] Gilles Deleuze, “Cours Vincennes: synthesis and time. 28/03/1978”

[37] Critique of Pure Reason¸ p.291, B209, A168.

[38] Critique of Pure Reason¸ p.295, A176, B217.

[39] Critique of Pure Reason¸ p.291, B209, A168.

[40] Gilles Deleuze, Logic of Sensation, p.58. Logique de la sensation, p.78-79.

[41] Deleuze, Logic of Sensation, p.83. Logique de la sensation, p.112.

.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment