[Search Blog Here. Index-tags are found on the bottom of the left column.]

[Central Entry Directory]

[Speculative Realism? entry directory]

[Other entries in the Merleau-Ponty phenomenology series.]

Deleuzean Differential Objects and Merleau-Ponty's Organisms

For Merleau-Ponty, the phenomenal object is something whose parts and properties organically integrate with one another.

Yet for Deleuze, an object, phenomenal or otherwise, is something made solely of difference.

So for Merleau-Ponty, an object's qualities are organically integrated. Any one of them already expresses the others and the whole they make-up.

An object is an organism of colours, smells, sounds and tactile appearances which symbolize, modify and accord with each other according to the laws of a real logic which is the task of science to make explicit, and which it is far from having analysed completely. (Phenomenology of Perception 45a / fr. 64)Let's distinguish Merleau-Ponty's sense of a phenomenal object from what a Deleuzean sort would be. What makes something an object? Normally an object is something whose parts hold together somehow. While it may be divisible into these parts, there is an element of indivisibility, or a dimension of indivisibility, which is like the glue that holds the parts together. So in Merleau-Ponty's case, the dimension of indivisibility lies in the integrated coherence of the parts, the holistic glue holding them together.

A Deleuzean object would be based solely on difference. Is Deleuze an emergentist and a process-relationalist, as some think? We all need not think so. Let's hold tight to his philosophy of difference. [To read some blog postings that seem to classify Deleuze in these other camps, see recent interesting discussions of: Adrian J Ivakhiv; Levi Bryant; and Graham Harman].

For Deleuze, an individual is like a calculus differential. It is a pure relation of difference without related parts. So in this way it is indivisible. But how can something indivisible also be a pure difference? Does not difference presuppose different things being differentiated? And thus would not an object made of difference also have parts being differentiated?

To illustrate a differential relation without related terms, Deleuze refers us to Leibniz' double triangle demonstration of the differential relation between vanishing values.

The sides of the smaller triangle begin with a particular ratio of one to the other. Because the larger triangle is proportional to the smaller one, the ratio of its sides is the same as for the smaller triangle. And as the smaller one shrinks, the larger one continues to maintain the smaller's ratio. Now we are to imagine the sides of the smaller triangle vanishing to the infinitely small. So they have no extensive finite value any more. However, the differential ratio between them remains. It can still be determined by the larger triangle. So here we have a differential relation without component terms, because they have vanished from the extensive world. Such a differential relation is an individual for Deleuze [For more, see Deleuze's Cours Vincennes 17/02/1981 and Cours Vincennes 10/03/1981].

So this individual is not divisible into its parts, because its parts have been divided already to infinity, leaving just the relation between them. Perhaps this is the closest thing we have to a Deleuzean 'object'. Yet note also that all bodies in extension can be considered as infinitely divided into these smallest parts, which make up larger bodies on the basis of more differential relations [for more on simplest bodies, again see Cours Vincennes 17/02/1981 and Cours Vincennes 10/03/1981; for how composition is a differential relation between simplest bodies, see this entry on Spinoza and rhythm].

So what about things we normally call objects, like beer bottles? How do we understand them in a Deleuzean way? It seems that the parts of the bottle hold together. Otherwise the beer would slip out.

Here, the Deleuzean object would not be the bottle, but the differential relations between the parts of the bottle and the parts of everything else. These are not the only differential relations. The parts within the bottle differentially relate in the same way, as between the glass and the cap. But the Deleuzean object is neither the glass nor the cap, it is the set of differential relations between the parts of each. These are 'objects' because as differential relations, they are relations between vanished terms, and hence are indivisible.

This is not yet speaking of the phenomenological object, but the Deleuzean phenomenal object is based on the same idea. We have microperceptions, which are also differential relations, just like the simplest bodies. [See this entry on differential perception for a more detailed explanation]. These microperceptions are too small for us to be explicitly aware of them. It is only when there is a differential relation between sets of these that there is a noticeable phenomenon. And this happens when the differential relation between them is so notable or remarkable that it flashes-out into our awareness. The bottle's difference from the table might strike us when we make use of that difference to lift the bottle. Then the difference between the beer and the bottle flashes before us when we tip the beer from the bottle to our mouths. But in each of these cases, the Deleuzean phenomenal object is not the beer and the bottle, for example, but instead the differential relations between, which we said were indivisible individuals. The differentiations between the microperceptions produces the larger macroperception.

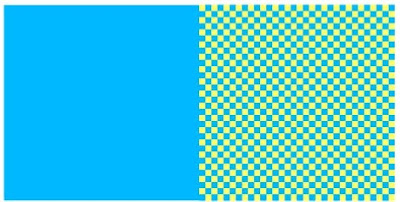

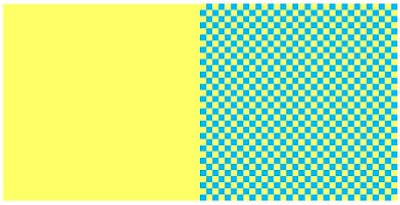

Why is this not emergentism? It might be, so long as we do not say that the emergent phenomenon is either the beer or the bottle. If there were such a thing as an emergent (phenomenological) phenomenon, it would be the collective impact that all the differential relations between the two has on our bodies. When the beer bottle stands-out to us, all the differential relations of its parts to those around it each affect us in different ways. But first consider a case where this might not seem to be so. [again, see this entry for more detail]. Green is the differential relation between yellow and blue, says Deleuze. When the yellow and blue parts diminish to the infinitely small, the microphenomena of yellow and blue become imperceptible, leaving just the differential relations between, which are green. This might seem like an emergent (phenomenal) phenomenon. And perhaps it is.

But also consider these two cases:

But this might only hold for perception. What if we were thinking about objects but not in terms of our perceptions of them. Would we think that the parts of an object like a beer bottle together produce the emergent object, the bottle itself with all its emergent properties? Such a view might think of the bottle's parts as being parts of an assemblage that is fluidly becoming, changing its arrangements so to become other objects, that is, other assemblages.

To find another view, let's first note an example of such a composed body that Deleuze discusses, the blood being made of lymph and chyle [again, see this entry on Spinoza and rhythm for a summary of the blood example]. The blood is constituted by the differential relations between the infinitely small parts of lymph to those of chyle. Blood would seem then to be an object emerging from its parts, lymph and chyle. These differential relations determine the blood's power, that is, its ability to affect other bodies and its capacity to withstand the affection of other bodies. But what also determines the blood's power is its differential relation to other bodies. The parts of blood are always in contact with other bodies. Consider for example when arsenic enters the blood. The differential relations of the blood will perhaps decrease in power. So the seeming 'emergent' object, the blood and its properties, is not just the emergent result of its parts. It is also the result of those parts' relations to the bodies impacting them. But the blood also affects the arsenic, perhaps by converting it to something less toxic. If there is anything of a constitutional nature, it is the differential contact between the arsenic and the blood. It is that differential contact which serves to constitute the parts.

The assemblege in this instance is the arsenic with the blood. In the case of the blood it is the lymph and the chyle. But as we noted, these are not really distinct assemblages. The only distinct things are the individuals, the differential relations which have no parts. We cannot speak of the blood's constitution without also speaking of the things it is differentially contacting. But even if we take those two things as parts of a greater whole, we only have that greater whole on the grounds that it is making a differential contact with another one. But what seems to be happening fundamentally is that all the differentials on the lowest level are in contact, and these seeming higher levels are arbitrary distinctions our minds make for practical purposes. The beer bottle is one object. When I go to drink from it, it is two objects. Really, it is an infinity of objects, which are merely differential relations.

Nonetheless, we still might think of Deleuze as a process philosopher. The differential relations seem always to be in flux. The bottle thrown to the sea becomes beach glass. The differenentials of the world seem always to be rearranging, the assemblages continually reassembling.

Yet, what we call the beer bottle is a set of differential relations, and these are all instantaneous affections [and again, see this entry on Spinoza and rhythm for the connection between simple bodies and affections]. This means the constitution of what we call the bottle, phenomenological or otherwise, is nothing temporal. The differential relations between simplest bodies is just how they are affecting one another at a given moment. The temporal continuity from one moment to the next is secondary to the differential constitution of things. Phenomenologically speaking it is on the grounds of differences from one moment to the next that something stands-out to us and is thus a phenomenon. So many phenomena are based on temporal discontinuities.

And what Deleuze calls 'becoming' might be something instantaneous. Deleuze writes that the event is something extensive. "That is clearly the first component or condition of both Whitehead's and Leibniz's definition of the event: extension. Extension exists when one element is stretched over the following ones, such that it is a whole and the following elements are its parts." [The Fold p.77bc] But is not becoming something intensive for Deleuze, rather than being something extensive? We might wonder, when we strike a match, what would be the wood's becoming fire? We might say it is a process that extends over the duration of the strike. But in a calculus sort of way, we might consider that instant at the limit before the flame breaks out. No time extends between it being wood and it being fire. It is virtually fire while actually being wood. When physicists determine instantaneous velocities, the objects are not actually going that speed, because there is no motion in an instant. But the instantaneous velocity is real, even though it is not actual. It is virtual. Becoming might be the simultaneous overlap of a fully real virtuality with an actuality, as in the case of the limit of fire and wood [see this entry on the paradox of becoming for more explanation]. But in terms of the differentials making up the wood and fire, we have the differentials of the wood differentiating from their very own selves, because they in their given place are both the differentials of the wood and the differentials of the fire, but contracted upon each other in the instant. This is Deleuzean becoming, as I understand it, which has little to do with the event. It is rather what he calls static genesis.

So in sum, Deleuze might not be a relationalist, because his differential relations do not have parts. He might not be an emergentist, because whatever we might consider to emerge from a substrate is conditioned just as much by other things as by its substrate. And Deleuze might not be a process philosopher, because becoming for him does not involve an extensively temporal event.

Deleuze, Gilles. The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque. Transl. Tom Conley. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. Transl. Colin Smith. London/New York: Routledge, 1958.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phénoménologie de la perception. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1945.

.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment