by Corry Shores

[Search Blog Here. Index-tags are found on the bottom of the left column.]

[Central Entry Directory]

[Deleuze Entry Directory]

[And may I also thank the sources of the images:

abcgallery.com; academics.smcvt.edu; all-art.org; Angie Hattingh; artchive.com; arthistory-archaeology.umd.edu; artexpertswebsite; avenuedstereo.com; Breana Melvin; club.quizkerala.com / Chandrakant Nair; dailyartfixx.com / Wendy Campbell; earlham.edu / Mark Van Buskirk; en.wahooart.com; escapeintolife.com; flickr.com /arak14; flickr.com / kraftgenie Gunther Stephan; frontpage.ccsf.edu; geweld.blogspot.com / Karel Goetghebeur

Grace Smith; Guggenheim; Iona Catholic Secondary School; inkhornterm.blogspot.com; mariabuszek; Matteson Art; Matt Nuzzaco at flickr.com; music.minnesota.publicradio.org;

mutualart.com; surrealist.com; tate.org.uk; thecityreview.com;ubuweb; uncg.edu; urbanartistscollective; wallpapers-free; Weber; wholesaleoilpainting4u.com; wikipedia; irea.wordpress / ABCdario; actingoutpolitics; midcenturyblog / Gatochy; students.sbc.edu; antiquity.tv; Ordinary Finds; scottzagar.com / Scott Zagar; Hillary Mayell for National Geographic News; Andy Wakely; Gerhard H. Kuhlmann; The Skilliter Centre for Ottoman Studies; easterrossfieldarchers.org; mysteriousworld.com; howstuffworks.com; microbion; mlahanas; wildfiregames; englishare.net; faq.macedonia.org; library.thinkquest.org; indianarog.com; trekearth.com / raszid62; chemistryland.com / Ken Costello; saintluc.over-blog.com; henrichy0205yt; glamourbombtv; Stephen Cornford; vr.theatre.ntu.edu; artnet.com; James R. Hugunin; artcritical.com; merzbarn.net; representingplace.wordpress.com; artintelligence.net; mousetrapcontraptions.com; Stephen Worth at ASIFA

Credits given below the image and at the end.]

We will try learning first from artists so we may provide an aesthetic sense for certain concepts we will later need to incorporate.

So we are looking for two main qualities in Dadaist art: 1) the relations between its aparts, and 2) the way this sort of relation is expressed in the functioning or form of the 'machinery' of the artwork.

We will follow a text that will help us answer these questions: William S. Rubin's Dada and Surrealist Art (1978).

Rubin has us consider the differences between a Picasso painting and a Jean Arp work (this will not be the same Picasso he shows, but a similar one).

Picasso, he writes, "is balanced and stabilizes and unfolds with a pictoral logic, though not predictability, which makes its stasis seem classically definitive." Yet Arp "may be turned any way; its contours unwind in a free and meandering manner implying growth and change." (Rubin 21Ac)

(Thanks artchive.com)

Jean Arp. Siamese Leaves (1949)

(Thanks mutualart.com)

The fact that we can turn the Arp any way we want suggests that although it has parts, they need not be set in any certain arrangement.

We will find this sort of freedom of parts also in the mechanical components of Duchamp's works, and we will begin with his paintings. Consider Nude Descending a Staircase, Number 2.

About it, Duchamp says, "A form passing through space would traverse a line; and as the form moved, the line traversed would be replaced by another line - and another and another." (Duchamp, quoted in Rubin 24Ad) Rubin writes: "Duchamp, like Leonardo, probably wanted to study motion in terms of the body as an unencumbered machine." (24Bb)

Consider also the "mechanism" (33) in another of Duchamp's paintings.

Duchamp discusses this period when he made these Cubist-like paintings. What he has to say will indicate to us something important about mechanics. It is not that the object or the movement can be broken-down into certain static parts. Rather, the object repeats itself, and each time in a new dimension in a sense. The repetition cannot happen at the same place or the same time, because then they would perfectly overlay. Each time they must be found in a new place and time, in a way; or we might at least say in a new dimension, or if not that, we might say in the same dimension, but incompatibly with the prior one. But is that not the same as a new dimension, anyway? He says "Repetition is the opposite of renewal. So it's a form of death." (Duchamp. Jeu d'échecs avec Marcel Duchamp. 49m, 10s) Now, repetitions in new dimensions are mechanical in a sense, because they are recurrences. But they are productively mechanical, because they produce new dimensions, or at least new dimensionalities, and they are differentially mechanical, because each production is a variation.

The Cubist method interested me then as repetition rather than deconstruction of the object, as it was later defined. It's the repetition of the same figures that interested me. The same figure repeated many times in one painting (Duchamp. Jeu d'échecs avec Marcel Duchamp. 29m, 45s)

He explains mechanics in terms of chess, a passion of his. He says of the game

It's logic and mechanics rather than mathematics. Mechanics in the sense that the pieces move, interact, destroy each other. They're in constant motion and that's what attracts me. Chess figures placed in a passive position have no visual or aesthetic appeal. It's the possible movements that can be played from that position that make it more or less beautiful. (Duchamp. Jeu d'échecs avec Marcel Duchamp. 26m, 50s)The play of the pieces is mechanical not just because they are in interactive motion, performing operations on one another. Another mechanical aspect are the variations that sprout from every position. Any one set-up can be full of intensity, full of variations of itself, full of ways to change the mechanics of the play. With each play, the mechanics change, because the pieces relate in a new way, with their inter-functioning altering accordingly. The series of piece-arrangements, changing with each move, is like his repetition-paintings. Each move takes us to a new dimension that is functionally divergent from the prior one. But when there is no next move except check-mate, then the game is dead. It is alive only as long as there are possible variations implied in the mechanics. We might even notice this in the workings of time. Another moment will follow this one only because variations are implied in this one, like the piece set-ups of the chess game. Difference in a way precedes change and time, as does repetition, or at least we might say proliferation if not repetition. This is part of the mechanics of time. Variations of the current moment are implicitly proliferated immediately right now. They are implicit in the sense that there is room for them to express themselves, but this so-called 'space' is all we might be able to sense. We can feel a certain intensity, which is the density or depth of the moment, its varying from itself instantaneously, and it undergoing a multiplicity of variations simultaneously. It is not like chess, where there are a finite number of determinate possible moves, each one pre-viewable, as a computer might do. There is, rather, difference and intensity, an instantaneous explosion of intensive 'space' (depth) for variations to pour into. So, each moment, we are in a new dimension, because each moment is incompossible with the prior one; they both cannot exist together, and yet they do, because these contracted layers of incompatible moments stack like sheets to produce the thickness of time. The Duchamp Cubist-like paintings can show us this and the mechanics behind it. Consider for example Duchamp's The Chess Players.

It shows two chess players at a table, in multiple views. The players are shown in different positions, suggesting the passage of time. Duchamp gave Cubism an idiosyncratic twist by introducing duration. The players are weighing their options. One potential outcome results in the capture, by the player on the left, of an opposing piece, held in his hand near the bottom of the painting. A picture of minds engaged in the calculus of chess, this is an early exercise in another continuing interest in Duchamp's art: depicting the intangible. (Andrew Stafford. Making Sense of Marcel Duchamp. Please see the 1904-1911 Section for an excellent illustration.)We will now take a look at Duchamp's works that are more physically mechanical. We will see that like the displacements in the paintings, these other works as well are based on a displacement of parts.

In 1913 he placed a bicycle wheel upside down on a stool [Bicycle Wheel 3rd Version]; singled out for contemplation in isolation from its normal context and purpose, it seemed strangely enigmatic, especially when the wheel turned pointlessly. What Duchamp had done was subject the wheel to the same kind of dépaysement - dissociation or displacement - as that to which the symbolist poets had subjected words in an attempt to liberate their hidden meanings." (Rubin, 36Bb, boldface mine)

There is a similar sort of mechanical displacement in his cinematic work, Anémic-Cinéma. Here he crafts short lines whose words go fine together, but each one also seems to stand-apart in a way. Consider this line, which reads:

ESQUIVONS LES ECCHYMOSES DES ESQUIMAUX AUX MOTS EXQUIS

Katrina Martin translates it as

'Let us flee from (cleverly and with some disdain) the bruises of the Eskimos who have exquisite words.' (Katrina Martin. Marcel Duchamp's Anémic-Cinéma, 58Bd)These words do not make coherent sense. But that does not stop us from reading them over and over. This of course could be a result of the phonetics. But it is more than just sounds, too. All together, the words operate on our thinking. But it is not because our minds make coherent sense of the words. There is a sort of functioning here without an integration of parts.

Let's for a moment jump to Man Ray for another articulation of this sort of relation between parts. He was inspired by a line in Isidore Ducasse's Les Chants de Maldoror (The Songs of Maldoror) (written under his pseudonym Comte de Lautréamont).

la rencontre fortuite sur une table de dissection d'une machine a coudre et d'un parapluieMan Ray gives a "literal representation of the metaphor:"

the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissection table

(Isidore Ducasse / Comte de Lautréamont. Les Chants de Maldoror / The Songs of Maldoror)

Man Ray undoubtedly assembled the appropriate objects - dissecting table, umbrella, and sewing machine; he made them "pose" in order to photograph them. (Renée Riese Hubert. Surrealism and the Book, p.193.)

(Renée Riese Hubert. Surrealism and the Book, p.193.)

We will return to this image later. But for now we notice that the parts do not cohere together. Yet somehow it works on our brain. And it is also not really on account of distantly associated things cohering with each other. More on this later.

Consider now Duchamp's Why not Sneeze Rose Sélavy?

Rubin writes of it that it is:

a birdcage filled with cubes of sugar, into which a thermometer and cuttlebone had been thrust. The spectator, having gotten over this unexpected juxtaposition, lifts the cage and discovers its great weight that the 'sugar lumps' are really cubes of white marble. (Rubin 37Abc)Here Duchamp explains this piece (after first discussing the bicycle wheel), noting the lack of connections between the parts and also between the parts and the title.

(Duchamp. Jeu d'échecs avec Marcel Duchamp.)

Rubin says that Duchamp's The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (with subtitle Delay; also known as the Large Glass)

Consists of two large panes of glass in metal frames forming together a field of little under nine feet tall and slightly under six feet wide. On one side of the glass a series of forms covering roughly a third of its surface have been applied with lead wire and paint. A spectator unfamiliar with Duchamp's iconography would not immediately divine that he was in the presence of a 'mechanistic and cynical interpretation of the phenomena of love' (Breton); he would had rather to respond to it as a perspective study for some strange and humorous machine of unclear purpose. He would note that, although the parts were connected mechanically, they are non-sequiturs in terms of individual identity. A waterwheel, a chocolate grinder, a cloud, and what appear to be cleaners blocking and pressing forms seem to function together like a very serious and scrupulously tooled counterpart of a Rube Goldberg apparatus (one of which was published by Duchamp in New York Dada) [with the caption 'I will now prove that a bullet doesn't lose any of its speed when it goes around corners.' April 1921] (Rubin, page citation number needed, boldface mine)

(dailyartfixx.com, Thanks Wendy Campbell)

Duchamp. Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), (1915-1923)

(Thanks Iona Catholic Secondary School)

Duchamp. Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), (1915-1923)

http://www.flickr.com/photos/clarapenin/4563577077/

(flickr.com, Thanks arak14)

And this, by the way, is the Rube Goldberg machine printed in Duchamp's New York Dada.

In the clip below, we see Duchamp discuss The Large Glass. [Also note a couple things in this clip: how 'Dada' means nothing and the movement was a 'series of totally uncoordinated actions', and as well note how he says he stopped working on the Large Glass when it reached a 'definitively incomplete' state.]

(Duchamp. Jeu d'échecs avec Marcel Duchamp.)

If you can, please see the animation and description at Andrew Stafford's Making Sense of Marcel Duchamp. It is remarkable- a wonderful analysis and visual demonstration of the mechanics behind the work. Do, do see it! You will need to move the time-line to 1923. Then Andrew Stafford proceeds to describe the different mechanisms and how they work. Note how many of the important mechanisms never saw completion, even though Duchamp stopped developing it when it was 'perfectly incompleted.' Duchamp apparently describes them in his notebooks, but never implemented them. Some such uncompleted parts are the spiral, splash region, waterspout, butterfly, boxing match and juggler. They are excluded, but they are necessary to explain the bizarre mechanics. And even if all the parts were there, the system can never arrive at a state of balance. The mechanisms seem to be striving for something, but all they really accomplish is the continuation of their motion, of their striving. Perhaps this is why it is subtitled 'a delay in glass.'

Duchamp's Tu m' 1918 also is reminiscent of a Goldberg machine of sorts. (We will return to this later.)

Duchamp. Tu m' (1918)

(Mainstreet, thanks Weber)

Duchamp. Tu m' (1918)

(Thanks en.wahooart.com)

Duchamp. Tu m' (1918)

(Thanks academics.smcvt.edu)

Duchamp. Tu m' (1918)

(Thanks Breana Melvin)

We see Dadaist machines also in Picabia.

Very Rare Picture on the Earth presents us with a strange pointless machine made of cylindrical tanks joined by pipes in a system apparently run by little wheels at the bottom. (Rubin 58Aab)Unlike in the case of Duchamp's machines, where there is a possible iconographic interpretation, "Picabia's machine remains a total enigma" (Rubin 58Aab).

Here are some more of Picabia's machines.

(Thanks tate.org.uk)

Picabia. Amorous Parade, (1917)

(Thanks music.minnesota.publicradio.org)

Picabia. Amorous Parade, (1917)

(Thanks arthistory-archaeology.umd.edu)

Picabia. Ici, c'est Stieglitz, (1915)

http://www.avenuedstereo.com/modern/images_week13.htm

(Thanks avenuedstereo.com)

Picabia. Novia, (1917)

(Thanks inkhornterm.blogspot.com)

Picabia. A little solitude amidst the suns (A picture painted to tell not to prove), (1919, 1915?)

(Thanks surrealist.com)

In these animations by Richter and Eggeling, we might also sense a certain Dadaist mechanics, perhaps between the motion of the parts.

(Ubuweb)

Viking Eggeling. Diagonale Symphonie / Diagonal Symphony, (1924)

(Ubuweb)

Let's also consider the works of Raoul Hausmann. We will be able to see more of a machinery sort of Dadaist organization. Hausmann, in the clip below, is quoted as saying that he thought himself more like an engineer building machines. When we see the collage works of Dadaists, we might still think in these machinery terms. In the very least we can see parts with heterogeneous relations. The collage, as a multiplicity, functions as an artwork, but there is no coherence to the roles that the parts play, like when there would be a larger logic of the system.

(Thanks ubuweb)

Hausmann. Spirit of Our Time (Mechanical Head), (1919)

(Thanks all-art.org)

Hausmann. Tatlin at Home, (1920)

(Thanks frontpage.ccsf.edu)

In the collage format, we have broken heterogeneity. The parts are incoherent, but they are still added together, as if by saying "... and ... and ... and ..." to conjoin the disjunctive elements. Consider here Kurt Schwitters' Das Undbild / The 'And' Picture.

(Thanks Angie Hattingh)

Kurt Schwitters. Das Undbild / The 'And' Picture (1919), detail

(Thanks Grace Smith)

Kurt Schwitters. Das Undbild / The 'And' Picture (1919), detail

(Thanks urbanartistscollective)

Also consider:

(Thanks artchive.com)

Kurt Schwitters. Merz Picture with Rainbow, (1939)

(Thanks escapeintolife.com)

Kurt Schwitters. Construction for Noble Ladies, (1919)

(flickr.com Thanks kraftgenie / Gunther Stephan)

Kurt Schwitters. NB, (1947)

(Thanks artexpertswebsite)

Kurt Schwitters from German Dada

(Thanks ubuweb)

And also:

(Thanks mariabuszek)

Man Ray. Coat Stand, (1921)

(geweld.blogspot.com Thanks Karel Goetghebeur)

Man Ray. Boardwalk, (1917)

(Thanks thecityreview.com)

We will now better clarify the Dadaist relations between parts by comparing it with Surrealism, which developed out of Dadaism. Rubin writes, "While this is an exaggeration, it is unquestionable that surrealist literature and art were, in some measure, an ordering and systematization of the chaotic inventions of Dada." (Rubin 116Bb) The relations between surrealist images often follow a 'flow of association' (Rubin 116Bb) and hence are not like the unassociated relations of Dada. And surrealist images, although made to look somewhat unusual, were still recognizable, like in dreams. "An object might be dreamed of as distorted, its perspective wrenched, but it is always an object familiar to us in our waking life." (Rubin 131Acd)

In Dadaist works, if the parts still cause us to have associations, then even so, for the most part, these associated images found on another level did not themselves associate with one another. In Surrealism, however, we see the opposite. While the different images might seem logically incompatible, their associated images still might weave together and integrate in a way that could possibly make some sort of vague and 'irrational' sense on another level of our consciousness. Dada, however, does not have this other level of coherence; there is not an unconscious logic, so to speak. Rubin has us recall the umbrella, dissection table and sewing machine, which we saw Man Ray depict.

(Renée Riese Hubert. Surrealism and the Book, p.193.)

There is no real coherence between the parts of the image. And even the associations each one gives us also seem not to integrate with each other. Umbrellas: rain; Sewing machine: clothes; dissection table: anatomy. Not much coherence. But instead we are to consider Giorgio de Chirico's The Song of Love.

Rubin says that again, these objects do not associate. But the images associated with the depicted ones 'cross-fertilize' each other. So the surgical glove might make us think of Western medicine, coming from the ancient Greeks, like in the Greek statue, and the Greeks appreciated pure forms, like the sphericity of the ball. And the knowledge of these Western-originating sciences led to technological advances seen much later in the steam engine for example. Also, the ball and the glove both call to mind rubber, and the glove makes us think of hands that would sculpt the statue or play with the ball. The coherence of the associations is vague and elusive. But think of the feeling it gives us. We feel as though there is some harmony to it all, even though on the surface none can be explicitly found. So it is not as though there is some story we can make-out from the associations. We cannot give any logical account for why these objects are placed together. But, as Rubin puts it, their associations, although also seemingly unrelated, 'cross fertilize' each other; they integrate in some unspecifiable, indirect way. [Rubin will also mention the head of Apollo Belvedere]:

The most literally dreamlike aspect of all in de Chirico's art consists of the extraordinary juxtapositions of ordinary objects in his paintings. As we know, contexts and levels of reality constantly mingle in dreams. What makes these minglings striking in de Chiric's art is not so much their presence per se as the quality of the poetry evoked by his particular confrontations... The juxtaposition, in The | Song of Love, of the head from an ancient Greek sculpture (Apollo Belvedere) with a surgeon's glove, a ball, and a distant locomotive, all set amid arcaded buildings, has the telling simplicity, force and directedness of Lautréamont's classic evocation. As with the latter's sewing machine, umbrella, and dissection table, each of de Chirico's objects calls forth associations that are rationally quite unrelated to the associations of the other objects. But crossfertilized, as they are in this painting, all these associations create a poetry in which a heretofore unsuspected metaphysics is revealed. (Rubin, page citation number needed)So let's also consider some works by Surrealist René Magritte.

Here the bottom night-scene is incoherent with the top day scene. But what is one of the first things we associate with the word night? Is it not often, day?

(irea.wordpress, Thanks ABCdario)

These images in the painting above are incoherent, but their associations with elegance at a social event are not incoherent.

(irea.wordpress, Thanks ABCdario)

We would never see such a thing, but we pour water into glasses, while umbrellas repel pouring rain.

(irea.wordpress, Thanks ABCdario)

This again is impossible, but flowers and sunshine associate well with one another.

Even when the coherence of the associations becomes less articulatable, we still have the feeling of there being another level of coherence, unlike with the Dada relations between parts.

(Thanks midcenturyblog, cited there as originally uploaded by Gatochy)

Magritte. The Acrobats Ideas, (1928)

(irea.wordpress, Thanks ABCdario)

Consider a couple works by Joan Miró, where also we feel the hidden coherence.

(Thanks students.sbc.edu)

Joan Miro. Dutch Interior, (1928)

(Thanks artchive)

Joan Miro. Catalan Landscape. The Hunter, (1923-1924)

(Thanks artchive)

Joan Miro. Tilled Field, (1923-1924)

(Thanks antiquity.tv)

So with all this in mind, we will turn now to Deleuze's and Deleuze & Guattari's ideas about machinery and non-associable relations of a functional assembly, working through their appendix to Anti-Oedipus, "Bilan-programme pour machines désirantes," translated to English in Chaosophy as "Balance-Sheet for 'Desiring-Machines'" (Thanks Clifford Duffy for pointing me to it).

Our final aim is to examine the D&G machinical sort of relations between parts and compare them to the organic sorts we find in Merleau-Ponty [I use 'machinical' rather than the conventional and more aesthetically pleasing 'machinic,' so to more blatantly announce its distinction with 'mechanical.' With this in mind, a 'machinic' could be the D&G parallel to a 'mechanic.' And to distinguish the two types of machines, we might consider 'machine' vs. 'mechine'. We will later see that in a mechine, the mechanisms mesh, but in a machine, the machinisms mash. Yet I will still use plainer terminology in the following.] We will take a brief look at some of their descriptions of machines and their workings.

D&G speak of absurd sort of machines in literature and art, which mis-operate

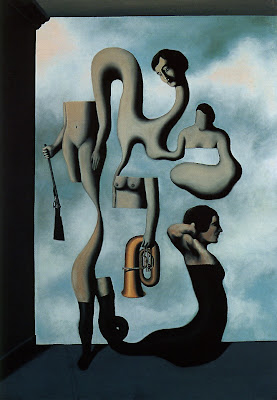

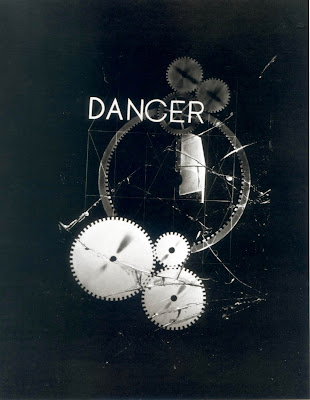

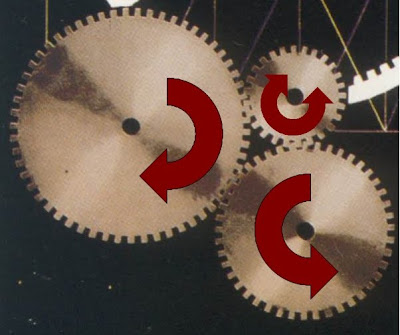

whether through the indeterminate character of the motor or energy source, through the physical impossibility of the organization of the working parts, or through the logical impossibility of the mechanism of transmission. For example, Man Ray's Dancer-Danger, subtitled "impossibility" offers two degrees of absurdity: neither the clusters of cog-wheels nor the large transmission wheel are able to function. (Deleuze & Guattari, "Balance-Sheet for 'Desiring-Machines', 91b.d)

(Thanks Ordinary Finds)

Man Ray. Dancer / Danger, Impossibility, (1920)

(scottzagar.com Thanks Scott Zagar)

(The Incompossibilities of the Gears' Motions)

Humans are component parts of machines. In the case above, we are to think in the first place that the gears' whirling is to express the twirling of a Spanish dancer. But the impossibility of the machine's workings is to convey the idea that a machine by itself could never perform something as non-mechanical as a human dancing. But the machine does express something about the motion. Implied in its entitled workings is the human dancer motions. Even though she is not shown, her necessity for completing the dance is implicit. This illustrates the need for humans to be a part of 'desiring machines'. For our phenomenological purposes, we are concerned more with the mechanics D&G are employing here. They go on to say that humans become components to machines when we communicate our functioning by recurrence to the other parts of the machine, all under the specific conditions of our functioning. The have us consider for example a mounted archer. What do a horse, a man, and a bow and arrow have to do with one another?...

(Thanks Hillary Mayell for National Geographic News)

(Thanks Andy Wakely)

(Thanks Gerhard H. Kuhlmann)

... nothing, except when on the steppes where war is waged. The recurrence of the horse's trot communicates its functioning to the man, whose recurrent pulling of his arm communicates to the recurrent springing of the bow and arrow. Normally, such recurrent functions would be meaningless to one another. Why should a horse care about a man's arm pulling back and forth? Why should the man care about the horse's feet moving up and down? But when they communicate the differences of their functioning under the conditions of war on the steppes, they together incoherently form a lethal war machine.

(Thanks The Skilliter Centre for Ottoman Studies)

(Thanks easterrossfieldarchers.org)

(Thanks mysteriousworld.com)

(Thanks howstuffworks.com)

In machines, "heterogeneous elements are determined | to constitute a machine through recurrence and communications" ("Balance-Sheet" 91-92).

But if we only thought of the mounted archer as being a means to kill enemies, then we are thinking of it as a tool rather than as a machine.

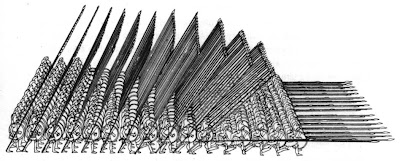

We will use their next example, the Greek phalanx, to better grasp the interworkings of the heterogeneous parts as springing-up out of the conditions of their functioning. D&G write "the Greek foot-soldier together with his arms constitute a machine under the conditions of the phalanx. [... | ...] Hoplite weapons existed as tools from early antiquity, but they became components of a machine, along with the men who wielded them, under the conditions of the phalanx and the Greek city-state." ("Balance-Sheet" 91d; 93bc)

(Thanks microbion)

(Thanks mlahanas)

(Thanks wildfiregames)

(Thanks englishare.net)

(Thanks faq.macedonia.org)

We can see the machinery of the phalanx in this clip above from the History Channel. But it is machinical not because it is like a gear in the army machine, or that it itself has gears, like the pike's fulcrum and the marching legs. It is a machine because these men and their mechanically-related parts form within the conditions of the heterogeneous machinery of their social and political circumstances. But being a citizen of a Greek city-state has nothing to do with wielding a long pike. They do not associate at all. Yet on the other hand, neither would have been able to sustain itself if both their heterogeneous functions were not combined. These civic conditions and the war machinery supporting them are inseparable. Forces bring these differentially-mechanical functions together. When we later turn to phenomenology, we will see that phenomena that appear to us have parts, yet these parts do not integrate organically, but rather have their heterogeneous motive tendencies forced together.

We normally think of machines and mechanisms as repeating a function, and the overall effectiveness of the machine we often regard as being the result of the mechanical parts maintaining their assigned function. But this is not really a machine, because it is not producing anything. It could be true that a machine at a factory continuously spits-out some manufactured product. But if it is the same product every time, than it has only produced one thing redundantly. So a real machine would have the capacity for new productions, and this would result from it being able to reconfigure itself and its functional relations with the functional mechanisms around it. So along with its power to connect with things around it and the power of its parts to connect together, it also has the power to form new connections and hence to break those already in function. ("Balance Sheet" 96c.d)

What defines desiring-machines is precisely their capacity for an unlimited number of connections, in every sense and in all directions. It is for this very reason that they are machines, crossing through and commanding several structures at the same time. For the machine possesses two characteristics or powers: the power of the continuum, the machinic phylum in which a given component connects with another, the cylinder and the piston in the steam engine, or even, tracing a more distant lineage, the pulley wheel in the locomotive, but also the rupture in direction, the mutation such that each machine is an absolute break in relation to the one it replaces, as for example, the internal combustion engine in relation to the steam engine. Two powers which are really only one, since the machine in itself is the break-flow process, the break being always adjacent to the continuity of a flow which it separates from the others by assigning it a code, by causing it to convey particular elements. ('Balance Sheet' 96c.d)So we are to consider the steam engine locomotive, first one with a cylinder and piston.

(Thanks library.thinkquest.org)

(Thanks wiki)

We notice the continuum of connections and functional transitions, which also connects the engineer to the ground the train covers. We might see this as well, they say, in an older version of the steam locomotive that used a pulley wheel. Ken Costello at chemistryland.com writes:

Anything that could burn could be used to turn water into steam. Once you had steam pressure you could get it to push a piston that would then turn a wheel. The large wheel (pulley) on top was fitted with a large leather belt. (Ken Costello. chemistryland.com)

(Thanks indianarog.com)

(trekearth.com Thanks raszid62)

(chemistryland.com Thanks Ken Costello)

But when internal combustion engines forced their way into usage, they broke the continuous connections of the steam engine. The engineer and his riders no longer were connected to the ground they traveled by means of steam-powered mechanisms. Internal combustion broke those continuous connections and inserted its own.

D&G now turn to machinic painters. Duchamp and Picabia, for example, do not paint a machine as if it were some object to be rendered, like a nude or a still life. Rather,

The aim is to introduce an element of a machine, so that it combines with something else on the full body of the canvas, be it with the painting itself, with the result that it is precisely the ensemble of the painting that functions as a desiring-machine. The induced machine is always other than the one that appears to be represented. It will be seen that the machine proceeds by means of an “uncoupling” of this nature, and ensures the deterritorialization that is characteristic of machines, the inductive, or rather the transductive quality of the machine, which defines recurrence, as opposed to representation-projection: machine recurrence versus Oedipal projection. ("Balance Sheet" 97a.b)The recurrences of a real machine are transductive, perhaps in the sense of transferring energy to new domains, as when the energy in our surroundings converts to the energy of our nerves' excitement. The recurrences would not be the same for example as when we might think our minds are consistently triggered to associate mental representations with our father or mother. But we will touch more on the anti-Oedipal characterizations of machines a bit later. For now we are looking at how painted machines are not depicted representations of machines but are instead parts of larger machines that include us as the viewers. Recall Duchamp's Tu m'.

With Duchamp, the real machine element is directly introduced, either standing on its own merits or set-off by its shadow, or, in other instances, having its place in the ensemble determined by an aleatory mechanism that induces the still-present representations to change roles and statues: Tu m’ for example. ("Balance sheet" 97d)We noted before that this work has a certain Rube Goldberg machine quality to it. So perhaps D&G are saying that our eyes work their way through the machinery of the painting, and when perhaps arriving at the shadow, the painting will unfold differently each time, perhaps depending on the angle we see it, but also the projecting part seems to take the mechanics out of the painting and directs them toward us.

In Picabia's work, the finished design connects up with the incongruous inscription, with the result that it is obliged to function with this code, with this program, by inducing a machine that does not resemble it. ("Balance sheet" 97c)Consider again for example Picabia's Daughter Born without a Mother / Fille née sans mère.

The National Galleries of Scotland site has this to say about the work:

The title alludes to the creation of Eve from Adam's rib and also to the Virgin birth. The gold background may refer to Renaissance paintings of the Virgin and Child. (National Galleries of Scotland)Our first reaction might be that this interpretation of the title could not possibly have anything to do with the painting, and that it seems completely irrelevant to what the painter is trying to achieve. But that illustrates D&G's point. The machinery here is neither the mechanisms depicted nor the title itself; rather the machine is the heterogeneous combination of both their functioning, along with us as the combining mechanism, as our minds try to put together two incompatible parts of our experience.

D&G also have us consider Léger's Ballet mécanique.

Léger demonstrated convincingly that the machine did not represent anything, itself least of | all, because it was in itself the production of organized intensive states: neither form nor extension, neither representation nor projection, but pure and recurrent intensities. ("Balance Sheet" 97-98)

We notice that the parts of the film seem to interact mechanically. But the mechanical functioning of any one segment does not extend into the functioning in the next segment. What does forming a smile have to do with the interchanging of circles and triangles? The functions do not extend into each other, but each one pushes-and-pulls upon its predecessor and successor, intending toward them rather than extending into them, and the disjointly conjoined parts then communicate their differences. We feel the resonance of these communicated differences as the intensive rhythm rather than as the extensive rhythm of the commonly-paced back-and-forth motions. These blatant conventional 'rhythms' are superfluous to the more profound machinical rhythm of intensive transductions, transfers of energy from segment to segment. We also see these intensive communications of functional difference within certain segments, as for example the scenes with working industrial machinery that stutters upon its own motion and functioning by means of kaleidoscopic overlays.

So there is a non-associativity involved in real machinery. D&G elaborate this by making use of the anti-Oedipal. They note how free association inevitably leads our thinking to Oedipal representations. It is almost as if there is something Oedipal about associations themselves. Perhaps it is the fact that associations are like mechanisms governing regimented representation. In a way, there is a sort of governance acting on our mental associations. And if we struggle to resist them, we are only entering into a fight with a governing power, like if a young man were to fight with his father. And is it that psychoanalysts try to identify our unhealthy mental associations, and then replace them with healthier ones? But what if instead of playing the association games, we made use of mechanisms that make non-associative connections?

Let us return to the necessity of breaking up associations: dissociation not merely as a characteristic of schizophrenia but as a principle of schizoanalysis. The greatest obstacle to psychoanalysis, the impossibility of establishing associations, is on the contrary, the very condition of schizoanalysis – that is to say, the sign that we have finally reached elements that enter into a functional ensemble of the unconscious as a desiring-machine. It is not surprising that the method called free association invariably brings us back to Oedipus; that such is its function. Far from testifying to a spontaneity, it presupposes an application, a mapping back that forces a preordained ensemble to associate with a final artificial or memorial ensemble, predetermined symbolically as being Oedipal. In reality, we still have not accomplished anything so long as we have not reached elements that are not associable, or so long as we have not grasped the elements in a form in which they are no longer associable. [ ... Then quoting Serge Leclaire: "...] What is involved, in brief, is the conception of a system whose elements are bound together precisely by the absence of any tie, and I mean by that, the absence of any natural, logical, or significant tie," "a set of pure singularities." [ft.11: Serge Leclaire, "La réalité du désir," in Sexualité humaine. Aubier (1971).] (“Balance-Sheet” 103a.b, boldface mine)So for example, if we analyze our dreams for associations, these associative mechanisms are not really productive, and they do not constitute a machine. However, D&G describe a method by Trost which can render dream analysis mechanical.

in order to retrace the dream thought […] it is necessary to break up the associations. To this end, Trost suggest [sic] a kind of à la Burroughs cut-up, which consists in bringing a dream fragment into contact with any passage from a textbook of sexual pathology, an intervention that re-injects life into the dream and intensifies it, instead of interpreting it, that provides the machinic phylum of the dream with new connections. The risk is negligible, since by virtue of our polymorphous perversity, the passage selected at random will always combine with the dream fragment to form a machine. And no doubt the associations re-form, close up between the two components, but it will have been necessary to take advantage of the moment, however brief, of dissociation to cause desire to emerge, in its nonbiographical and nonmemorial nature, beyond as well as on this side of its Oedipal predeterminations. (“Balance Sheet” 102b.c)Recall the distinction we made between Surrealism and Dadaism. The Surrealist associations integrated (or they at least 'cross-fertilized'), but the Dadaist ones did not. Dadaism is machanical because its parts con-operate non-associatively, but Surrealism is associative and Oedipal. Real machines contain

a set of really distinct parts that operate in combination as being really distinct (bound together by the absence of any tie). such approximations of desiring-machines are not furnished by surrealist objects, theatrical epiphanies, or Oedipal gadgets, which function only by reintroducing associations – in point of fact, Surrealism was a vast enterprise of Oedipalization of the movements that preceded it. But they will be found rather in certain Dadaist machines, in the drawings of Julius Goldberg, or, more recently, in the machines of Tinguely. How does one obtain a functional ensemble, while shattering all the associations? (What is meant by “bound by the absence of any tie”?). (“Balance Sheet” 104a)We will first look at Tinguely's machines. In Jean Tinguely's mechanical artworks, we also have heterogeneity of parts and functions, all for seemingly a purpose that has got to do with nothing else at all, nothing else other than pulling us into it, conjoining us to it so that we together make a bigger machine without a pre-established purpose. Here is one to look at:

D&G will refer us to Tinguely's Rotozaza. See this instance for example.

In Tinguely, the art of real distinction is obtained by means of a kind of uncoupling used as a method of recurrence. A machine brings into play several simultaneous structures which it pervades. The first structure includes at least one element that is not operational in relation to it, but only in relation to a second structure. It is this interplay, which Tinguely presents as being essentially joyful, that ensures the process of deterritorialization of the machine, as well as the position of the mechanic as the most deterritorialized part of the machine. The grandmother who pedals inside the automobile under the wonderstruck gaze of the child – a non-Oedipal child whose eye is itself a part of the machine – does not cause the car to move forward, but, through her pedaling, activates a second structure, which is sawing wood. Other methods of recurrence can be put into play or added-on, as, for example, the envelopment of the parts within a multiplicity (thus the city-machine, a city where all the houses are in one, or Buster Keaton’s house-machine, where all the rooms are in one). Or again, the recurrence can be realized in a series that places the machine in an essential relationship with scraps and residua, where, for example, the machine destroys its own object, as in Tinguely’s Rotozazas, [...] or | it is itself made up of scraps as in Stankiewicz's Junk Art, or in the Merz and the house-machine of Schwitters, or, finally, where it sabotages or destroys itself, where "its construction and all the beginning of its destruction are indistinguishable." ("Balance Sheet" 104b.105a)We will turn to Buster Keaton shortly. We should note now how the parts of the machine are not functional in relation to one another, but only to a third part of the machinery, with the example being a grandmother pedaling the automobile while a child stares wonderstruck at it, but the pedaling's function is conjoined not with the car's movement but with the sawing of wood. I do not have this piece displayed yet, but we have this moment from a newsreel showing a boy seemingly perplexed with a Tinguely machine.

(youtube.com. Thanks glamourbombtv)

Note how his body moves in response. He is not quite acting against the machine's movements, because he is so glued to it. But on the other hand, he is not mimicking the machine or acting in correspondence with it. Rather, he is like another of its heterogeneous mechanisms, affected by the rest, contracted upon them, but acting differentially to them.

Here by the way is a Tinguely machine that "sabotages or destroys itself, where 'its constuction and all the beginning of its destruction are indistinguishable.'" [Also note the necessity for human interaction to assist the machinery's operation].

Here is some of Stankiewicz's 'Junk Art.'

(Thanks vr.theatre.ntu.edu)

Stankiewicz. Untitled

(Thanks artnet.com)

Stankiewicz. Our Lady of All Protections, (1958)

(Thanks artnet.com)

Stankiewicz. The Apple

(Thanks James R. Hugunin)

And here again is some Merz by Schwitters.

And here is his Merz 'house-machine'.

(Thanks merzbarn.net)

(Thanks representingplace.wordpress.com)

(Thanks artintelligence.net)

(Thanks ubuweb)

Recall also mention of Buster Keaton's 'house-machine,' "where all the rooms are one" ("Balance Sheet" 104d). D&G also write:

Picabia called the machine "the daughter born without a mother." Buster keaton introduced his house-machine, with all its rooms rolled into one, as a house without a mother, and desiring machines determine everything that goes on inside, as in the bachelors' meal ("Balance Sheet" 95d)And here in his first Cinema book Deleuze writes:

Another method might be called the machine gag. Keaton’s biographers and commentators have emphasised his liking for machines, and his affinity in this respect with Dadaism rather than Surrealism: the house-machine, the ship-machine, the train-machine, the cinema-machine. . . . Machines and not tools: this is the first important aspect of his difference from Chaplin, who advances by means of tools, and is opposed to the machine. But in the second place, Keaton makes machines his most precious ally because his character invents them and becomes part of them, machines 'without a mother' like those of Picabia. They may get out of control, become absurd, or be absurd from the start, complicate the straightforward, but they never cease to serve a secret higher finality which is at the heart of Keaton’s work. The model house in One Week, whose parts have been put together in disorder and which becomes a | maelstrom; The Scarecrow, where the single-roomed house 'without a mother' muddles each potential room with another, each cogwheel with another, stove and gramophone, bath and couch, bed and organ. These are the house-machines which Keaton, the Dadaist architect par excellence, designs. (Deleuze, Cinema 1, 1986: 179c.180a)

Notice in The Scarecrow how familiar mechanisms take on new mechanical relations. All these normal household things should be associatively related, but because the house has been machinized, they now con-function heterogeneously. Things not normally together are forced into one another, like the gramophone turntable and the stove-top, the bathtub and sofa, and the bed and organ.

Keaton’s ‘trajectory gag’ is machinized like this too. Every segment is functionally compacted upon a prior one, even though each transduction is non-associatively related. Altogether, the machinical segments make one larger trajectory machine. Here for example are scenes from Sherlock Jr and The Three Ages.

Deleuze refers us to another Keaton machine, which will transition us back into our reading of "Balance Sheet", with its next paragraph on Rube Goldberg.

These ‘minorations’ can only take place through the processes of physical causality, which pass through detours, extensions, indirect paths, liaisons between heterogeneous elements, providing the absurd element which is indispensable to the machine. Already in the ‘Malec’ series, the High Sign puts forward a bizarre abridgment of the causal series: a shooting machine in which the hero presses his foot on a hidden lever, so that a system of wires and pulleys brings down a bone which a dog tries to reach by pulling a cord so that the bell on the target rings (a cat is enough to throw the mechanism out of gear). We are reminded of the drawings of Rube Goldberg – also Dadaist – the prodigious causal series where ‘posting a letter’, for example, passes through a long succession of disparate mechanisms, each engaging with the others, beginning with a boot which sends a rugby ball into a tub, and, passing through interlocking mechanisms, finishes by unraveling before the sender’s eyes a screen on which is written You Sap Mail that Letter. Each element of the series is such that it has no function, no relationship to the goal, but acquires one in relation to another element which itself has no function or relation. . . . These causalities operate through a series of disconnections: like Keaton’s, some of Tinguely’s machines string together several structures, each including an element which is not functional but which becomes so in the one that follows (the grandmother who pushes the pedals of the car does not make the vehicle move forward, but triggers off an apparatus for sawing wood . . .). (Deleuze, Cinema 1, 1986: 181a.c)Here is the scene from the High Sign.

Moreover, it is chance relations that ensure this, without, between elements which are really distinct as such, or the unconnective connection of their autonomous structures, following a vector that goes from mechanical disorder towards the less probable, and which we call the "mad vector." The importance here of Vendryes' theories becomes evident, for they make it possible to define desiring machines by the presence of such chance relations within the machine itself, and by its production of Brownoid movements of the sort observed in the stroll or the sexual prowl. And, in the case of Goldberg's drawings as well, it is through the realization of chance relations that the functionality of really distinct elements is ensured, with the same joy that is present in Tinguely, the schizo-laughter. What is involved is the substitution of an ensemble functioning as a desiring-machine positioned on a mad vector, for a simple memorial circuit or for a social circuit (in the first example, You Sap, Mail that Letter), the desiring-machine pervades and programs the three automated structures of sport, gardening, and the birdcage; in the second example, Simple Reducing Machine, the Volga boatman's exertion, the decompression of the stomach of the millionaire eating dinner, the fall of the boxer onto the ring, and the jump of the rabbit are programmed by the record insofar as it defines the less probable or the simultaneity of the points of departure and arrival). (Deleuze & Guattari, Balance-Sheet for "Desiring-Machines", 105b.d)

And here are the Rube Goldberg machines that Deleuze and D&G reference:

(Thanks mousetrapcontraptions.com)

(Deleuze & Guattari. Anti-Oedipus, French edition, between pages 464 and 465)

Could not Keaton have just run the rope directly to the bell? Why involve a dog outside under uncontrolled conditions? As a result, the dog links-up with a new mechanism, the cat, which causes Keaton to look either like he is cheating or that he is incredibly expert at shooting. But the cat sent shocks of differentiation throughout the machine, causing it to function differently, to in a sense become a different machine. We notice that in nearly all of Rube Goldberg's machines, at least one of the differentially mechanical conjunctions involves a human or animal. This helps introduce chance contingencies into the functional operation, and creates probabilities for certain functional flows to be cut off while others are conjoined, as when Keaton's flow to the dog-bone mechanism is cut-off because of the dog's distraction with the cat, while also the cat introduces a new flow and direct connection to Keaton. So one aspect of Deleuze's differential mechanics is the freedom of the parts to disjoin, which might result from another aspect, the heterogeneity of the parts' functions. Note the functional heterogeneity in this Rube Goldberg machine.

The parts' functions would normally not associate with one another. But we see how they con-operate under the conditions of the necessity to put out the fire. So they are disjunctively functional, we might say. What does an Eskimo getting hot have to do with a moose-head becoming heavy? What does a waiter being distracted by money on the ground have to do with extinguishing a fire?

There is another dimension of machinery that we will make use of when applying these concepts to phenomenology. There is something like a revolutionary power to their workings. One way this is explained is with the concept of minorization. Large machines might establish a regime, but then those machines get used in a diminished way by a minor faction or force in the system. By minorizing the regimenting machines, the minor powers create a new machinical operation, still perhaps using the same machinery. D&G write:

One of the greatest artists of desiring-machines, Buster Keaton was able to pose the problem of an adaptation of the mass machine to individual ends, or to those of a couple or small group, in The Navigator, where the two protagonists "have to deal with house-keeping equipment generally used by hundreds of people (the galley is a forest of levers, pulleys, and wires)." [ft 14, p. 305c: David Robinson, "Buster Keaton," Revue du Cinéma (this book contains a study of Keaton's machines).] ("Balance Sheet" 108ab)

And Deleuze:

In The Navigator the machine is not merely the great liner by itself: it is the liner apprehended in a 'minoring' function, in which each of its elements, designed for hundreds of people, comes to be adapted to a single destitute couple. The limit, the limit-image is thus the object of a series which does not set out to breach it, or even to reach it, but to attract it, to polarise it. By which system can a little egg be cooked in a huge pot? In Keaton, the machine is not defined by immensity. It implies immensity, but in inventing the 'minoring' function which transforms it, by virtue of an ingenious system which is itself machinic, based on the mass of pulleys, wires and levers. [ft. 16.] [Deleuze, Cinema 1, 1986: 180b]

We will now apply these concepts of Dadaist machinery to Deleuze and Merleau-Ponty's theories of phenomena.

We discussed before how phenomena in Merleau-Ponty involve integrations. [For a summary, please see this entry. More detail can be found among the entries here]. The general idea is that all parts of our phenomenal awareness are implied in each other. To see the carpet's color is also to implicitly have the lighting and what shades it in the margins of our awareness. When we notice ambiguities in the margins of our attention, it motivates our awareness to turn away from what is in the forefront of our conscious and direct it toward what is implied. So in the carpet we might see a shadow that does not look like any of the furniture, and then we turn up our heads and see a person. The carpet's shade of color had a particular look to it, and it implies the phenomenon of the standing person. By moving from the shadow to the person, we make explicit what was previous implied in a related phenomenon.

So for Merleau-Ponty, when our awareness is turned to something new, it is on account of that new phenomenon's implication in what we just previously were noticing. This is a sort of phenomenological motivation. It is mechanical in a way, because it pivots our awareness. And we might say that it is also associative. When we see one thing, in it is suggested already in all other phenomena, and we can explicate these other 'suggestions' by turning our awareness toward them. So we would say that each part of our phenomenal awareness associates with the others, and by means of these associations, our attention mechanical pivots from one to the next.

Our Deleuzean phenomenology is more concerned with the phenomenality of phenomena. Something appears insofar as it stands-out before us. And something stands-out to the extent that it differs from its context. So the more sudden and non-associative something is, the more it will stand-out, and the more phenomenal it will be. But for Merleau-Ponty, when a new phenomenon appears to us, it does so because its associative relations caused our awareness to mechanically pivot toward it.

Let's instead try to conceive phenomenal mechanics in terms of what we discussed regarding Dadaist machinery. What makes us turn our attention from one thing to the next would not at all be the association. It would be the fact that something in the margins of our awareness does not associate with what we now see, and it is the difference that calls to our attention. Why would we care to turn our awareness to what is already implied in what we now see? How boring! How unphenomenal. Really, who cares? If there is any mechanism that turns our attention to something new, it would be difference, things that don't fit in, things that don't associate with what we now see. The more non-associative, the more phenomenal. The nine eleven terrorist attacks presented images and feelings that had nothing to do with what we were feeling earlier in that day, nothing whatsoever. And how phenomenal it was. What we saw, jet planes inserting into skyscrapers, were two things in our perception that refuse to go together, and yet there they are, smashed together with unstoppable force. We need not show the image here. It can pop vibrantly into our head. Why is it so vivid? Because it separates itself out so strongly from every other image we might have. We spoke before of minor uses of the available major machinery. When something stands-out, it does not really appear from nowhere. It was already there in the margins of our awareness, functioning in the given phenomenal machinery. (It could already have been there in the margins of our awareness, or it could have been composed of phenomena not new to us like buildings and jets). Nothing normally will stand-out in the margins or among recognizable things, because all these phenomena already interrelate and imply one another associatively. We usually do not need to turn our attention to the things in the margins of our attention, because they are already given to us indirectly even without or explicit awareness of them. Our consciousness is already implicitly moving mechanically among them, as if already jumping from one to the next, and thus does not actually need to do so. Associative phenomenal machinery is always already at work, and it keeps things below the threshold of our interest. Something will stand-out to us only when part of our field of awareness appropriates one of the many implied phenomenal mechanisms of motivation and converts it from associative to non-associative. When we noticed the odd shadow on the carpet, we turned our attention because one of the small associative relations, in this case between the carpet-shadows and the objects creating them, stopped associatively interweaving with the other phenomena. This shadow did not associate with the ones made by the furniture. The object we assumed to be causing this did not fit-in with the other things in our field of perception. We turned our attention to it only because a non-association had the motor-power to change the mechanics of our phenomenal workings. Phenomenal appearances, in a way, are like minorized appropriations of our phenomenal apparatus. All it takes is one little gear to become non-associative, and then the whole machine can assemble into a new one, like with Merleau-Ponty's beached boat example.

So in our Deleuzean phenomenology, the equivalent of phenomenological motivation would be non-associative mechanisms, and the relations between parts of our phenomenal awareness would be understood as having a Dadaist sort of logic to their arrangement, like in Merz collages or Buster Keaton's machines. To close, I would like to include a moment from a Stan Brakhage monologue/self-interview. Here he explains very well the differential mechanics of phenomenal appearances. Notice what he says toward the end about how his attention is turned not between things that he would usually think to belong together, but rather between things he normally would not think to be juxtaposed. In other words, dissociative relations are the motivational mechanisms for the succession of appearances, and not associative integrations, as would be the case for a Merleau-Pontian phenomenology.

Works cited:

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. Transl. Hugh Tomlinson & Barbara Habberjam, London: Continuum, 1986.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. "Bilan-programme pour machines désirantes," appendix to L'Anti-Oedipe. Paris: Les éditions de minuit, 1972/1973.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. "Balance-Sheet for 'Desiring-Machines'" in Félix Guattari Chaosophy: Texts and Interviews 1972-1977. Ed. Sylvère Lotringer. Transls. David L. Sweet, Jarred Becker, & Taylor Adkins. Los Angeles: Félix Guattari and Semiotext(e), 2009.

Hubert, Renée Riese. Surrealism and the Book. Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 1988.

Preview available at:

http://books.google.be/books?id=9_3g0tHPgPwC&hl=en&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Lautréamont, Comte de. (Isidore Ducasse). Les Chants de Maldoror.

http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/12005/pg12005.html

Martin, Katrina. 'Marcel Duchamp's Anémic-Cinéma.' Studio International 189, no. 973 (Jan. - Feb. 1975): 53-60.

https://www.msu.edu/course/ha/850/katymartin.pdf

Motherwell, Robert. The Dada Painters and Poets, An Anthology. Cambridge/London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1981.

Rubin, William S. Dada and Surrealist Art. London: Thames, 1978.

Stafford, Andrew. Making Sense of Marcel Duchamp.

Fantastic online resource with demonstrations, explanations, and superb animations. Good analysis and explication.

http://www.understandingduchamp.com/

Videos

Brakhage, Stan, Stephen E. Gebhardt & Robert Fries. "Legendary Epics Yarns and Fables: Stan Brakhage." Available at:

http://www.ubu.com/film/brakhage_yarns.html

Duchamp. Anémic-Cinéma

http://www.ubu.com/film/duchamp_anemic.html

Hans Richter-Rhythmus 23 (1923).avi

http://www.ubu.com/film/richter_rhythm_1923.html

Eggeling. Diagonale Symphonie

http://www.ubu.com/film/eggeling.html

Duchamp. Jeu d'échecs avec Marcel Duchamp (1963). Available at:

http://www.ubu.com/film/duchamp_chess.html

Herbst, Helmut. German Dada. (1969). Available at:

http://www.ubu.com/film/herbst.html

Léger. Ballet mécanique (1924)

http://www.ubu.com/film/leger.html

Tinguely boy newsreal:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cl_WVGDzxT4

(Thanks glamourbombtv)

Tinguely Homage to New York

http://vimeo.com/8537769

(Thanks Stephen Cornford)

Images:

Apollo Belvedere

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Belvedere_Apollo_Pio-Clementino_Inv1015.jpg

(Thanks wikipedia)

Apollo Belvedere, detail head

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Belvedere_Apollo_Pio-Clementino_Inv1015_n3.jpg

(Thanks wikipedia)

Arp, Jean Arp. Siamese Leaves

http://www.mutualart.com/Artwork/Siamese-Leaves/63C6CEA19E63C495?promo=PHO345

(Thanks mutualart.com)

de Chirico. Song of Love

http://www.mattesonart.com/magic-realism-giorgio-de-chirico-.aspx

(Thanks Matteson Art)

Duchamp. Bicycle Wheel

http://www.flickr.com/photos/nuzz/3215489661/

(Thanks Matt Nuzzaco at flickr.com)

Duchamp. Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors

http://www.dailyartfixx.com/2009/07/28/marcel-duchamp-1887-1968/

(dailyartfixx.com, Thanks Wendy Campbell)

Duchamp. Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even

http://www.dpcdsb.org/IONAS/Courses/Visual+Arts+Gr+12.htm

(Thanks Iona Catholic Secondary School)

Duchamp. Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even

http://www.flickr.com/photos/clarapenin/4563577077/

(flickr.com, Thanks arak14)

Duchamp. The Chess Players

http://www.abcgallery.com/D/duchamp/duchamp1.html

(Thanks abcgallery.com)

Duchamp. Nude Descending a Staircase

http://www.uncg.edu/rom/courses/dafein/civ/nude_no2.jpg

Duchamp. Portrait of Dulcinea

http://www.wallpapers-free.co.uk/background/paintings/marcel_duchamp/portrait-of-dulcinea/

(Thanks wallpapers-free)

Duchamp. Sad Young Man in a Train

http://www.wholesaleoilpainting4u.com/AD/p_detail_D709.html

(Thanks wholesaleoilpainting4u.com)

Duchamp. Tu m'

http://weber.blogs.sapo.pt/103227.html

(Mainstreet, thanks Weber)

Duchamp. Tu m', side view

http://bremelvin.com/wordpressbre/?p=630

(Thanks Breana Melvin)

Duchamp. Tu m'

http://en.wahooart.com/A55A04/w.nsf/Opra/BRUE-7YLJ6W

(Thanks en.wahooart.com)

Duchamp. Tu m'

http://academics.smcvt.edu/gblasdel/slides%20ar333/webpages/m.%20duchamp,%20tu%27m%20ennuies.htm

(Thanks academics.smcvt.edu)

Duchamp. Why not Sneeze Rose Sélavy, 1921

http://www.earlham.edu/~vanbma/20th%20century/images/dayten04.htm

(earlham.edu Thanks, Mark Van Buskirk)

Duchamp. Why not Sneeze Rose Sélavy, 1921

http://club.quizkerala.com/2009/03/26/daily-question-166/

(club.quizkerala.com Thanks Chandrakant Nair)

Goldberg, Rube. machine color

http://www.animationarchive.org/2008/10/comic-strips-rube-goldbergs-side-show.html

(Thanks Stephen Worth at ASIFA)

Goldberg, Rube. Letter mailing

http://www.mousetrapcontraptions.com/rube-cartoons-2.html

(Thanks mousetrapcontraptions.com)

Goldberg, Rube. Rube Goldberg / Duchamp cartoon in New York Dada, from

Motherwell, Robert. The Dada Painters and Poets, An Anthology. Cambridge/London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1981.

Hausmann. Spirit of Our Time (Mechanical Head)

http://www.all-art.org/art_20th_century/hausmann1.html

(Thanks all-art.org)

Hausmann. Tatlin at Home

http://frontpage.ccsf.edu/artarchive/index_09.html

(Thanks frontpage.ccsf.edu)

Heartfield, Jean. Cover for Der Dada #3 (1920)

http://www.mariabuszek.com/kcai/GenresMedia/1-4Images.htm

(Thanks mariabuszek)

Magritte. Empire of Light

http://irea.wordpress.com/2008/11/03/artista-del-mes-rene-magritte/

(irea.wordpress, Thanks ABCdario)

Magritte. The Happy Hand 1953

http://irea.wordpress.com/2008/11/03/artista-del-mes-rene-magritte/

(irea.wordpress, Thanks ABCdario)

Magritte. Hegel's Holiday

wordpress.com/2008/11/03/artista-del-mes-rene-magritte/

(irea.wordpress, Thanks ABCdario)

Magritte. The Conqueror 1926

http://www.actingoutpolitics.com/rene-magritte%E2%80%99s-%E2%80%9Cthe-conqueror%E2%80%9D-1926-%E2%80%93-how-to-put-a-bully-and-thug-into-a-tuxedo-and-a-bowtie/oba

(Thanks actingoutpolitics)

Magritte. Personal Values

http://midcenturyblog.blogspot.com/2010/08/magritte-personal-values-1951.html

(Thanks midcenturyblog, cited there as originally uploaded by Gatochy)

Magritte. The Acrobats Ideas

http://irea.wordpress.com/2008/11/03/artista-del-mes-rene-magritte/

(irea.wordpress, Thanks ABCdario)

Miro, Joan. The Harlequin's Carnival

http://www.students.sbc.edu/evans06/presentation.htm

(Thanks students.sbc.edu)

Miro, Joan. Dutch Interior

http://www.artchive.com/artchive/m/miro/dutchint.jpg

(Thanks artchive)

Miro, Joan. Catalan Landscape. The Hunter, 1923-1924

http://www.artchive.com/artchive/M/miro/hunter.jpg.html

(Thanks artchive)

Miro, Joan. Tilled Field

http://www.antiquity.tv/episode-5-salvador-dali-artist-profile/

(Thanks antiquity.tv)

Picabia. Amorous Parade, 1917

http://music.minnesota.publicradio.org/features/0003_satie/gallery/picabia.shtml

(Thanks music.minnesota.publicradio.org)

Picabia. Amorous Parade, 1917

http://www.arthistory-archaeology.umd.edu/ARTHwebsitedecommissionedNov32008/webresources/resources/modules/modern/sld012.htm/

(Thanks arthistory-archaeology.umd.edu)

Picabia. Ici, c'est Stieglitz

http://www.avenuedstereo.com/modern/images_week13.htm

(Thanks avenuedstereo.com)

Picabia. Novia

http://inkhornterm.blogspot.com/2007_10_01_archive.html

(Thanks inkhornterm.blogspot.com)

Picabia. A little solitude amidst the suns (A picture painted to tell not to prove)

http://www.surrealist.com/artists/Francis%20Picabia/53f389bd-870b-4bfd-9b4e-3c8b8249a36a.html

(Thanks surrealist.com)

Picabia. Daughter Born without a Mother

http://www.tate.org.uk/modern/exhibitions/duchampmanraypicabia/rooms/room4.shtm

(Thanks tate.org.uk)

Picabia. Very Rare Picture on the Earth

http://www.guggenheim.org/new-york/collections/collection-online/show-full/piece/?search=Dada&page=1&f=Movement&cr=3

(Thanks Guggenheim)

Picasso. The Guitar Player

http://www.artchive.com/artchive/P/picasso/cadaques.jpg.html

(Thanks artchive.com)

Ray. Man Ray. Dancer / Danger, Impossibility.

http://i12bent.tumblr.com/page/459

(Thanks Ordinary Finds)

Ray. Man Ray. Dancer / Danger, Impossibility.

(scottzagar.com Thanks Scott Zagar)

Ray. Man Ray. Reproduction of L'image d'Isidore Ducasse. In Renée Riese Hubert. Surrealism and the Book, p.193.

http://books.google.be/books?id=9_3g0tHPgPwC&dq=%22Surrealism+and+the+book%22&hl=en&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Ray. Man Ray. Coat Stand

http://geweld.blogspot.com/2008/04/ventilators.html

(geweld.blogspot.com Thanks Karel Goetghebeur)

Ray. Man Ray. Boardwalk

http://www.thecityreview.com/f03cimp2.html

(Thanks thecityreview.com)

Schwitters, Kurt. The 'And' Picture / (Das Undbild) 1919

http://www.ifashion.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1832&Itemid=263

(Thanks Angie Hattingh)

Schwitters, Kurt. The 'And' Picture / (Das Undbild) 1919, detail

http://www.neurosoftware.ro/programming-blog/facebook-web-design/web-resources/get-creative-with-collage-trends-and-inspiration/

(Thanks Grace Smith)

Schwitters, Kurt. The 'And' Picture / (Das Undbild) 1919, detail

http://urbanartistscollective.wordpress.com/2010/02/12/express-yourself/

(Thanks urbanartistscollective)

Schwitters, Kurt. Blauer Vogal Blue Bird

http://www.artchive.com/artchive/S/schwitters/bluebird.jpg.html

(Thanks artchive.com)

Schwitters, Kurt. Merz Picture with Rainbow (1939)

http://www.escapeintolife.com/essays/kurt-schwitters-citizen-of-the-world/

(Thanks escapeintolife.com)

Schwitters, Kurt. Neues Merzbild (New Merzpicture) (1931)

http://www.artchive.com/artchive/S/schwitters/new_merz.jpg.html

(Thanks archive)

Schwitters, Kurt. Construction for Noble Ladies, 1919

http://www.flickr.com/photos/kraftgenie/5041055053/

(flickr.com Thanks kraftgenie / Gunther Stephan)

Schwitters, Kurt. NB

http://www.artexpertswebsite.com/pages/artists/schwitters.php

(Thanks artexpertswebsite)

Schwitters, Kurt. Merz House / Merzbau images:

http://www.merzbarn.net/merzbarn/merzbauten/

(Thanks merzbarn.net)

http://representingplace.wordpress.com/tag/house/

(Thanks representingplace.wordpress.com)

http://artintelligence.net/review/?p=29

(Thanks artintelligence.net)

Stankiewicz. Song of the Little Frog

http://vr.theatre.ntu.edu.tw/fineart/th9_207/2005-th9_207-10.htm

(Thanks vr.theatre.ntu.edu)

Stankiewicz. Untitled

http://www.artnet.com/galleries/Artwork_Detail.asp?G=&gid=112961&which=&ViewArtistBy=&aid=628701&wid=425601662&source=artist&rta=http://www.artnet.com

(Thanks artnet.com)

Stankiewicz. Our Lady of All Protections, 1958,

in "Miracle in the Scrap Heap: The Sculpture of Richard Stankiewicz," Aug. 13-Sept. 25, 2003,

at the AXA Gallery, 787 Seventh Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10019 8/14/03

http://www.artnet.com/magazine/picturepostcard/picturepostcard2003.asp

(Thanks artnet.com)

Stankiewicz. The Apple

http://www.uturn.org/synapsis/

(Thanks James R. Hugunin)

Stankiewicz. Playground

http://artcritical.com/2003/08/21/gallery-going-a-version-of-this-article-first-appeared-in-the-new-york-sun-august-21-2003/

(Thanks artcritical.com

Tinguely machine:

http://saintluc.over-blog.com/article-ut-pictura-poesis-38078192-comments.html

Thanks saintluc.over-blog.com

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QLVOTM5rKrc

( Thanks henrichy0205yt)

Van Gogh. Mulberry Tree

http://mathematics.dikti.net/seni_vincent_van_gogh.html

Thanks mathematics.dikti.net

Van Gogh. detail from Mulberry Tree

http://www.flickr.com/photos/saimo_mx70/2484266257/

Thanks saimo_mx70

Mounted archer images:

http://www.skilliter.newn.cam.ac.uk/frontier.shtml

(Thanks The Skilliter Centre for Ottoman Studies)

http://www.easterrossfieldarchers.org/history2.html

(Thanks easterrossfieldarchers.org)

http://www.mysteriousworld.com/Journal/2003/Autumn/Giants/

(Thanks mysteriousworld.com)

http://people.howstuffworks.com/samurai.htm/printable

(Thanks howstuffworks.com)

http://andywakeley.com/blog/2008/04/21/a-few-more-horse-sketches/

(Thanks Andy Wakely)

http://www.ghkuhlmann.de/kureng/glossary.html

(Thanks Gerhard H. Kuhlmann)

http://www.abolitionist.com/darwinian-life/genghis-khan.html

(Thanks Hillary Mayell for National Geographic News)

Hoplite weapons:

http://www.microbion.co.uk/graphics/c4d/c4d-models.htm

(Thanks microbion)

http://www.mlahanas.de/Greeks/images/Hoplite4thcentury.jpg

(Thanks mlahanas)

http://www.wildfiregames.com/forum/index.php?showtopic=11557

(Thanks wildfiregames)

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf004MercenaryWarBarcidSpain.html

(Thanks mmdtkw.org)

http://www.englishare.net/literature/POL-LDS-Apology.htm

(Thanks englishare.net)

http://faq.macedonia.org/images/phalanx.jpg

(Thanks faq.macedonia.org)

Locomotive images:

http://library.thinkquest.org/04oct/01249/website/background.html

(Thanks library.thinkquest.org)

http://www.trekearth.com/gallery/Europe/Poland/photo1183692.htm

(trekearth.com Thanks raszid62)

http://www.indianarog.com/allotherengines.htm

(Thanks indianarog.com)

http://www.chemistryland.com/CHM151W/05-Gases/Gases/PuttingGasesToWork151.htm

(chemistryland.com Thanks Ken Costello)

Combustion engine animation:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Arbeitsweise_Zweitakt.gif

(Thanks wiki)

Steam Engine animation:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Steam_engine_in_action.gif

(Thanks wiki)

Train cylinder piston animation

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Walschaerts_motion.gif

(Thanks wiki)

.jpeg)