by Corry Shores

[Search Blog Here. Index-tags are found on the bottom of the left column.]

[Central Entry Directory]

[Deleuze on Bacon Entry Directory]

[May I sincerely thank the sources of the images

Credits are given below the image and at the end.]

Difference & Sensation:

Further Elaborations of Deleuze's Diagram,

Aesthetic Analogy, and Modulation

What do aesthetic analogies, diagrams, and modulations got to do with you?

We might think that when we recognize something, we are sensing it. But the more we recognize something, the less it stands out to us. We often can take our daily route to work and arrive without paying much attention to what happened in the meantime. But if the light turns red while we were distracted, we see it with little time left to stop, then the traffic light stood out. It appeared as something distinct and phenomenal. This is because the action it demands of us is strongly different from our ability to comply with it. There was an enormous force between it and our car, as if it were putting up a shield to us as we step on the break. The red light in a way directly touches our foot to make it stomp, but it pushes us away so we do not enter the intersection. So really it is differential relations that make things appear to us, and not recognizable things. If we stare at something for too long, our vision fades, the scene before us ceases to be phenomenal. But if we are able to continue staring at something with interest, because we continue to notice new things about it like variations we had not noticed before, then the object can remain as a phenomenon.

In such a case, what we see from one moment to the next is a variation. We can stare at the same object, but so long as we notice new differential variations in it, the object will continue to change for us; its parts will modulate from one moment to the next.

So we might then take interest in a couple things, if we wanted to know what makes something stand out in its significance to us when we perceive it. We want to know, what causes the modulation? Because there are variations, it would be some sort of differential mechanism. And what causes its phenomenality in our experience of it? Since the phenomenon appears only when something new about it enters the scene, then perhaps phenomenality has something to do with the confusions or puzzlements that changes cause us when they conflict with the assumptions we had of the thing.

Brief Summary:

Deleuze's theory of sensation is based on certain concepts that require thorough and careful analysis to explicate. These concepts are diagram, aesthetic analogy, and modulation. A diagram is a differential mechanism that causes variations in how things are appearing to us. An aesthetic analogy is the variations that the diagram causes. The aesthetic analogy is analogous in a way that makes us connect it with its former appearance, but now its parts relate in a different way, which causes us to notice the incompatibilities. Each presentation is a system of differential relations. When the two are contracted together in the instant when they collide in our perceptual experience of them, intense differences flash between the two given systems of differences. This flash is the phenomenon! It tells us something significant is there. It is what we call a sign.

Points Relative to Deleuze:

A Deleuzean phenomenology would be based on such a principle of differential shocks between differential systems of perception.

To explain his theory of sensation, Deleuze proposes a highly complex and obscure concept, aesthetic analogy. This idea is central to his thinking, so we will carefully analyze the text where he uses the term.

Let's initially look at Deleuze's concept of the 'diagram.' We might begin first with a conventional concept of a diagram. We noted Peirce's for example. He defined the diagram as having relations between its parts which resemble the relations between the represented thing's parts, even though there may be no sensible resemblance between the two. So consider a body accelerating in a straight line through space. When we plot its progress on a diagram with one axis as distance and the other time, we might find it to be a curve. But that does not at all look like how the object moved. Nonetheless, the correlations between the represented values of time and distance resembles the actual correlations between the moving body's positions relative to the time passed.

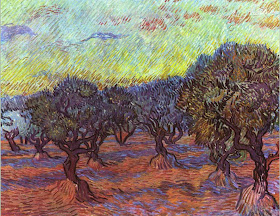

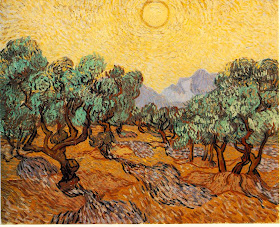

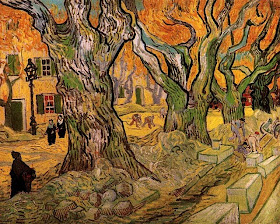

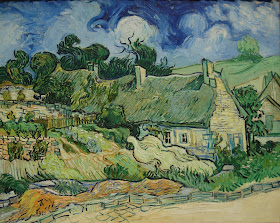

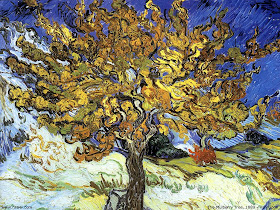

Deleuze will refer to 'diagrams' in paintings. Like conventional diagrams, these are visual, and they are fixed in their place. However, Deleuze's diagrams have force and power. Even as static beings, they are pushing-and-pulling around parts of the painting, or are acting in some other way to produce an implicit instantaneous-dynamic in the image. Deleuze says that they are 'operative;' they are in force; they are an acting force or influence on the painting. "The diagram is the operative set of traits and color-patches, of lines and zones" (Deleuze Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation 72ab). Deleuze offers this example: "Van Gogh's diagram, for example, is the set of straight and curved hatch marks that raise and lower the ground, twist the trees, make the sky palpitate, and which assume a particular intensity from 1888 onward." (72b)

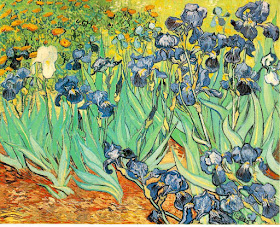

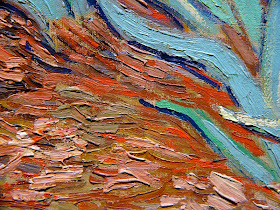

Let's take a look at what Deleuze might mean by the hatch marks in Van Gogh's paintings.

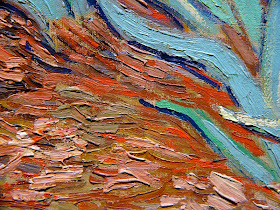

Here is a detail, showing the texture.

Van Gogh. Detail from The Irises, 1889

(Thanks pbase)

Perhaps from the image we can see how these marks 'raise and lower the ground.' Or maybe this is more evident in other works.

Perhaps more evident here.

There we also see the sky palpitating.

Here as well.

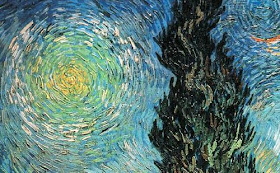

Van Gogh. Starry Night, 1888

(Thanks wikimedia)

Here are some details.

Here we see the trees being twisted by the hatch marks.

What do we notice with these markings? They seem to twist, pull, melt the colors and forms they comprise. And yet they themselves are dried paint. They are stagnant, fixed, still. Yet do we not feel the forces tearing at the tree or the sky?

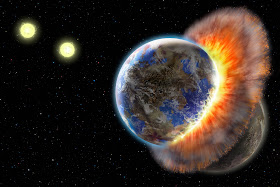

What we seem to have is instantaneous motion. But it is not a snapshot that captures a blurry motion. The motion is implied in the forces acting to twist the parts around. We anticipate some imminent change, but we cannot predict it. We can only feel the mix of forces. So in a sense, these lines are a chaos, even in their fixed form. And yet, this multiplicity of twisted tendencies never ceases to affect us. There is no actual motion in the painting. But the variations in its suggested motion never cease shifting and surprising us. It continually suggests that the parts of the painting are changing their relations to each other, for otherwise we would not sense an implicit continually varying motion. Now if when viewing the work we find that the tree for example ceased seeming to move, then this action of the diagram would no longer influence the painting. There would be a sort of entropy, all the energy exhausting itself until all the forces cancel, and it ceases to appear implicitly dynamic. We might consider some image where there is an explosive collision depicted.

Astronomy Picture of the Day 2008 September 25

(Thanks NASA)

As we initially examine it, we might feel the force of the collision. The exploding and incinerating sections might act as a diagram, causing the parts to feel as though they are getting pushed-and-pulled chaotically in a multiplicity of directions, all under the influence of an extraordinary power. We might then at first feel an intense event with incredible forces being expressed. But after a while, we will not see a pending event, or a moment in an incredible action, but just two balls floating together, bound peaceably to one another by a ruff collar. Gradually, the forces of variation dissipate. It is for this reason that I think Deleuze also credits the diagram as being a "germ of order or rhythm." I would not say that the above collision picture, after its forces have dissipated, would be ordered. There would be no forces for such an order. The Van Gogh Mulberry Tree, however, is sort of like a perpetual motion machine.

Despite its chaotic form, we might say it suggests much more order than the planetary collision image. Order is not so much a static, neutered structure, where all the forces have lost their competitive edge. Rather, order is persistence. But when differences reduce each other, there is not persistence but rather dissipation into redundancy. Hence the germ of order is not something that promises regularities, but rather promises ceaseless variations. And also, Deleuze does not use 'rhythm' to mean redundancy. Rhythm is fundamentally atemporal, and also like a germ. Rhythm happens when our normal patterns change. Rhythm is not a pattern. Rhythm is the force that keeps patterns alive by varying them, modulating them, preventing them from disappearing into redundancy [See this entry on how Deleuze derives this meaning of 'rhythm' from Messiaen and Boulez']. Our interaction with the mulberry tree is rhythmic not because our experience of it has something like a 'steady beat.' Our interaction with the mulberry tree is rhythmic, because we are never allowed to summarize the motion in our mind, to reduce it to some defining description or representational image. It is rhythmic because it creates Bergsonian duration, a continual emergence of variation, time as continual self-differentiation rather than a homogeneous space or motion. The structural components responsible for this promise of continual variation, like Van Gogh's hatch marks, are what Deleuze calls a diagram.

Thus we may already clarify one of the two major differences between Deleuze's and Peirce's diagrams. Peirce's diagram fixes relations between its parts so to analogously represent the relations between the parts of something else, which bears no sensible resemblance to the diagram. Deleuze's diagram however produces the forces which prevent any possibility for the relations to remain fixed or representational. Later we will see that the second major difference is that unlike in Peirce's case, Deleuze's diagram does involve sensible resemblance.

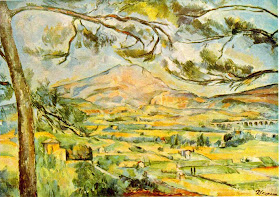

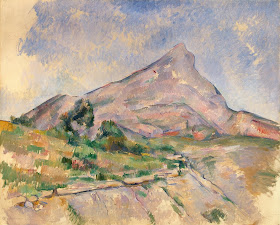

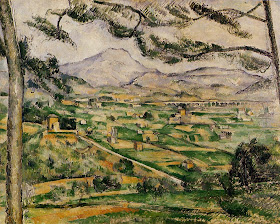

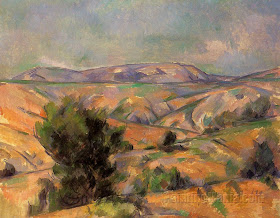

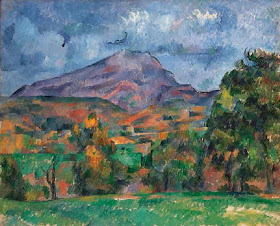

We look now at another of Deleuze's examples of a diagram in painting: Cézanne's 'motif'. He writes,

Few painters have produced the experience of chaos and catastrophe as intensely, while fighting to limit and control it at any price. Chaos and catastrophe imply the collapse of all the figurative givens, and thus they already entail a fight, the fight against the cliché, the preparatory work (all the more necessary in that we are no longer "innocent"). It is out of chaos that the "stubborn geometry" or "geological lines" first emerge; and this geometry or geology must in turn pass through the catastrophe in order for colors to arise, for the earth to rise toward the sun. [ft.1] It is thus a temporal diagram, with two moments. But the diagram connects two moments indissolubly: the geometry is its 'frame" and color is the sensation, the "coloring sensation." The diagram is exactly what Cézanne called the motif. In effect, the motif is made up of two things: the sensation and the frame. It is their intertwining. A sensation, or a point of view, is not enough to make a motif: the sensation, even a coloring | sensation, is ephemeral and confused, lacking duration and clarity (hence the critique of impressionism). But the frame suffices even less: it is abstract. The geometry must be made concrete or felt, and at the same time the sensation must be given duration and clarity. [ft.2] Only then will something emerge from the motif or diagram. Or rather, this operation that relates geometry to the sensible, and sensation to duration and clarity, is already just that: it is the outcome, the result. (78bc-79a, boldface mine)

So we are looking then for 1) an indication of what Cézanne's 'motif' might be, 2) the way chaos is involved in it, 3) the way geometry or geology (the frame) passes into color or sensation, by means of the motif or diagram, causing the two components to intertwine and 4) the way this places the sensation into duration.

From a variety of indications, we might gather that Cézanne's motif is whatever he was painting and perhaps what he repeatedly painted. In most cases this is a landscape, and the common trend in these references is that Montagne Sainte-Victoire (or at least his view on it) is considered what he calls his motif. Mont Sainte-Victoire is the mountain ridge in south France, located near Cézanne's home. For example, in a letter to Emile Zola, he writes regarding someone named "Monsieur Gilbert,

Where the train passes close to Alexis's country house, a stunning motif appears on the east side: Ste Victoire and the rocks that dominate Beaureccueil. I said: "What a lovely motif"; he replied: "Those lines are too well balanced." (Cézanne, Letter to Zola, Aix, 14 April, 1878, pp.158-159)

We find more explanation of Cézanne's motif in the "Memories of Paul Cézanne" of Emile Bernard; here we find another such indication.

"I was going to my motif," he told me, "let's go together." (55b) [...] Cézanne picked up a box in the hall and took me to his motif. It was two kilometers away with a view over a valley at the foot of Sainte-Victore, the craggy mountain which he never ceased to paint in watercolor and in oils. He was filled with admiration for this mountain. [...] I left him at his motif, in order not to disturb his work [...]. (Conversations with Cézanne p.56b,c).

Soon we left the studio to go to our motif. He took me to a view of Mont Sainte-Victoire and each of us began our study [...]. (69d)

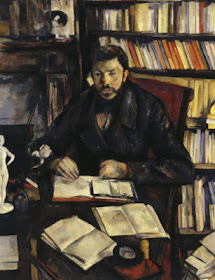

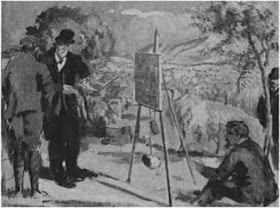

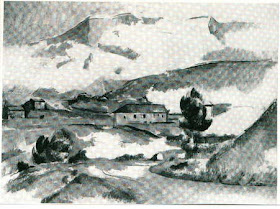

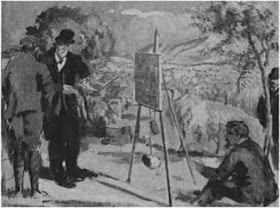

And here is a painting, by Denis Maurice, titled Cézanne à son motif, depicting Cézanne painting what appears to be Mont Sainte-Victoire

Denis Maurice. Cézanne à son motif

(From, Conversations with Cézanne, p.91)

[Here are some other places in Conversations with Cézanne where he seems to refer to Mont Saint-Victoire as his motif p.60ba,d; speaking of driving to his motif, perhaps either the mountain or some other landscape: 77a; 83c]

When not referring to the mountain, note the description of disorder involved in the setting.

We went into the studio where Cézanne came only to work and where an indescribable disorder reigned, the pipe of an ancient water-pump climbing up toward a skull, which, posed on a face oriental carpet, composed a still-life motif. (Francis Jourdain, "Excerpt from Cézanne" Conversations with Cézanne 82b)

This passage suggests that he repaints the same scene repeatedly during a period of time:

he was less interested in painting the violent contrasts that the untamed sun imposes than the delicate transitions which model objects by almost imperceptible degrees. He painted modulated light rather than full sunlight. For this artist, | who worked for several years on the same motif, a ray of sun or a reflection were only rather bothersome accidents of secondary importance. (Rivière and Schnerb, "Cézanne's Studio" Conversations with Cézanne 88-89)

Joachim Gasquet recalls a time when he accompanies Cézanne to his motif in " 'What He Told Me . . .' Excerpt from Cézanne," especially the section titled "The Motif."

Before us, under the virgilian, lay Mont Sainte-Victoire. [...]. [...] | This is the landscape Cézanne painted. He worked on his brother-in-law's land, where he had set up his easel in the shade of a stand of pines. [...] His chosen image, meditated upon, linear in its logic, and which he must have quickly sketched out in charcoal, as was his habit, began to emerge from the colored patches that encompassed it on all sides. The landscape seemed to be fluttering, because Cézanne had slowly delimited each object, sampling, so to speak, each tone. Day after day he had imperceptibly and with a sure harmony brought together his color values. He linked them to one another in a veiled brightness. Volumes emerged, and the great canvas reached its maximum equilibrium and saturation of color, which, according to Elie Faure, are characteristic of all of his paintings. The old master smiled at me.

CÉZANNE: The sun shines and fills my heart with hope and joy.

ME: You are happy this morning?

CÉZANNE: I have my motif . . . (He clasps his hands together.) A motif, you see, it is this . . .

ME: What?

CÉZANNE: Oh, yes! (He repeats his gesture, separates his hands, spreading his fingers apart, and brings them slowly, very slowly together again, then joins them, clenches them, intertwining his fingers.) That's what you have to attain. If I go too high or too low, all is lost. There must not be even one loose stitch, a gap where emotion, light, and truth can escape. Try to understand, I guide my entire painting together all the time. I bring together all the scattered elements with the same energy and the same faith. Everything we see is fleeting, isn't it? Nature is always the same, but nothing about her that we see endures. Our art must convey a glimmer of her endurance with the elements, the appearance of all her changes. It must give us the sense of her eternity. What is beneath her? Perhaps nothing. Perhaps everything. Everything, you understand? So, I join her wandering hands . . . I pick her tonalities, her colors, her nuances form the left, from the right, here, there, everywhere. I fix them; I bring them together . . . They form lines. They become objects, rocks, trees, without my thinking about it. They take on volume. They have color values. If these volumes and values correspond on my canvas and in my senses, to my planes and patches, that you also see before you, well, my painting joins its | hands together. [...] if I have the least distraction, the slightest lapse, if I interpret too much one day, if today I get carried away with a theory that contradicts yesterday's, if I think while I am painting, if I intervene, then bang! All is lost; everything goes to hell.

ME: What do you mean, "if you intervene"?

CÉZANNE: An artist is only a receptacle for sensations, a brain, a recording device . . . Damn it, a good machine, but fragile and complex, especially where others are concerned . . . But if it intervenes, wretched thing, if it dares of its own will to intervene in what it should only translate, if its weakness infiltrates the work, the painting will be mediocre. [...] Art is a harmony parallel to nature. [...] They are parallel, if the artist doesn't intentionally intervene [...]. His entire will must be silent. He must silence all prejudice within himself. he must forget, forget, be quiet, be a perfect echo. The full landscape will inscribe itself on his photographic plate. In order to fix it on his canvas, to exteriorize it, his craft comes into action. But it must be a respectful craft which, itself also, is ready only to obey, to translate unconsciously so long as it knows its language well, the text it deciphers, these two parallel texts; nature seen and nature felt, the nature which is out there . . . (he indicates the blue and green plain) and the nature which is in here . . . (he taps himself on the forehead) both of which must unite in order to endure, to live a life half human, half divine [...]. The landscape is reflected, becomes human, and becomes conscious in me. I objectify it, project it, fix it on my canvas. [...] Both my painting and the landscape are outside of me. One is chaotic, fleeting, confused, and without logical being, external to all logic. The other is permanent, tangible, organized, participating in the modality and drama of ideas . . . and in their individuality. (Conversations with Cézanne 109d-111d, boldface mine)

In the above text, we get the sense that his motif is the intertwining of the world and the art piece accomplished through the mediation of the painting. The painter does not necessarily photograph the work. But his brain is to receive an imprint of the sensation. The painter then finds the right color arrangement which will produce the same imprint in the viewer's brain as the painter himself originally had in that unique moment of interaction with the world. This takes the disorganized world and places our fleeting impressions of it in a durable form. This requires a 'translation' process that will not make an exact representational copy of the original scene, but will rather aim to make a reproduction of the original affection the painter had when allowing himself to be confronted openly and willingly with the chaos of the world. Gasquet recounts more dialogue by Cézanne on this topic. And here Cézanne again refers to Mont Sainte-Victoire as providing this painter-world confrontation. He begins by saying that the artist's brain should be a recording device, but what it records is color, because that is its point of contact with the world.

What I am trying to explain is more mysterious. It's tangled up in the very roots of existence, in the intangible source of our sensations. [...] I told you earlier that the brain of the artist, at the moment he creates, should be like a photographic plate, simply a recording device. (113a) [...]

Color is the place where our brain meets the universe. [...] Look at Sainte-Victoire. What animation, what overpowering thirst for sun! [...] These boulders were made of fire. There is still fire in them. (113d) [...]

Painting his motif Mont Saint Victoire involves and incredible encounter between himself and the world. This seems to involve him first getting a sense of the geological structure on the basis of feeling how the layers slowly 'erupted' over eons of time. He then approaches the world as though it were all completely new to him. This allows him to sense the infinitely many nuances in the world which may normally go undiscovered on account of our conventionally or habitually grouping differences together for the sake of recognizing parts of the world. But in this pure state, all in a sense is difference, an infinity of nuance or variation. The world for him in that encounter is pure variation. He loses himself in his painting and becomes one with it, but in the form of an 'iridescent chaos.' First Cézanne composes the geological formations. But catastrophic forces palpitate the geological lines, causing them collapse as and become reorganized into patches of color. This event happens when Cézanne breaks from his immersion into the scene. He feels as though disruptive forces from within the earth erupt into the geological formations.

For a long time I was powerless, I didn't know how to paint Sainte-Victoire, because I imaged, just like all the others who don't know how to see, that shadows were concave. But look, it is convex; its edges recede from its center. Instead of becoming stronger, it evaporates, becomes fluid. (114a) [...]

In order to paint a landscape correctly, first I have to discover the geographic strata. Imagine that the history of the world dates from the day when two atoms met, when two whirlwinds, two chemicals joined together. I can see rising these rainbows, these cosmic prisms, this dawn of ourselves above nothingness. [...] I breathe the virginity of the world in this fine rain. A sharp sense of nuances works on me. I feel myself colored by all the nuances of infinity. At that moment, I am as one with my painting. We are an iridescent chaos. I come before my motif and I lose myself in it. I dream, I wander. Silently the sun penetrates my being, like a faraway friend. It warms my idleness, fertilizes it. We germinate. When night falls again, it seems to me that I shall never paint, that I have never painted. I need night to tear my eyes away from the earth, from this corner of the earth into which I have melted. The next day, a beautiful morning, slowly geographical foundations appear, the layers, the major planes form themselves on my canvas. Mentally I compose the rocky skeleton. I can see the outcropping of stones under the water; the sky weighs on me. Everything falls into place. A pale palpitation envelops the linear elements. The red earths rise from an abyss. I begin to separate myself from the landscape, to see it. With the first sketch, I detach myself from these geological lines. Geometry measures the earth. A feeling of tenderness comes over me. Some roots of this emotion raise the sap, the colors. It's a kind of deliverance. The soul's radiance, the gaze, exteriorized mystery are exchanged between earth and sun, ideal and reality, colors! An airborne, colorful logic quickly replaces the somber, stubborn geography. Everything becomes organized: trees, fields, houses. I see. By patches: the geographical strata, the preparatory work, the world of drawing all cave in, collapse as in a catastrophe. A cataclysm has carried it all away, regenerated it. A new era is born. The true one! The | one in which nothing escapes me, where everything is dense and fluid at the same time, natural. All that remains is color, and in color, brightness, clarity, the being who images them, this ascent from the earth toward the sun, this exhalation from the depths toward love. Genius would be to capture this ascension in a delicate equilibrium while also suggesting its fight. I want to use this idea, this burst of emotion, this smoke of existence above the universal fire. My canvas is heavy, a heaviness weighs down my brushes. Everything drops. Everything falls toward the horizon. From my brain onto my canvas, from my canvas toward the earth. Heavily. [...] To paint in its reality! And to forget everything else. To become reality itself. To be the photographic plate. To render the image of what we see, forgetting everything that came before. (Conversations with Cézanne 114b-115b)

Deleuze sees the diagram involved in this encounter with the world. What we have is the structure of the scene (the frame) converting into patches of color in accordance with Cézanne's sensation. This happens when the forces of the earth rise up to the sun, catastrophically disrupting the "stubborn geometry" of the scene. Now, this eruption into the frame is not literally a volcanic eruption of the mountain. It must be something else. The disruption seems to be in the encounter, what happens when the givens of the world meet the scrambled, confused, and cross-wired neural paths of the human nervous system. The brain then is a photographic plate, not so much of the exact visual pattern of the original scene, but of its rearrangement and deformative process that it undergoes in accordance with the "uncertain" processing of our nervous systems. But note also that the disruption of the structural givens occurs when Cézanne approaches the world in a naive way that sees only nuance, that is, only pure variation or difference. Our sense apparatuses have the power to take in everything in pure differentiated form, to perceive pure difference. We might focus on the 'chaos' involved in this. But more essential is difference. The world is given to us as an infinite multiplicity of differences. Our bodily contact then adds differences to those differences. It breaks it apart, rending cracks throughout what we see, to produce new differences between broader regions. In Cézanne's case he breaks the given into color patches. Originally given to him were not color patches as much as they were geometrical geological formations. But on account of the difference-generation that occurs when we contact the world as a difference to the world (Cézanne says he breaks away from the scene), while also receiving the world as a pure heterogeneity of difference, we may render the structure into a sensational form. The sensation of color, for Cézanne, is the point of contact between the brain and the world. So he finds the colors that can reproduce the sensation of this differential impact he has with his scene. I want to emphasize that this idea of the diagram's injection of chaos can be made more precise. When the world's differential variations meet our sense-apparatus' differential variations, we then have two differential variations that are now forming against one another a new differential variation. Chaos we might conceive as this collision of differences, these variations of variations. It need not only be understood merely as a lack of order or pattern. These traits are not the primary features, they are the concequences of differences colliding and causing one another to resonate and shake from the differential encounter.

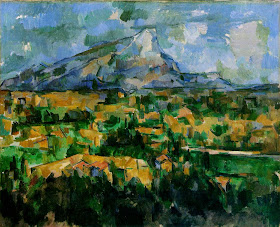

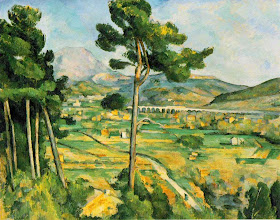

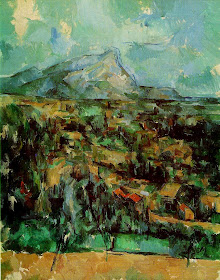

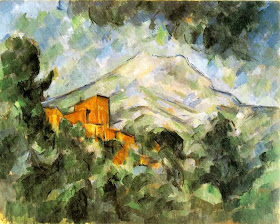

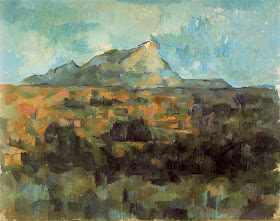

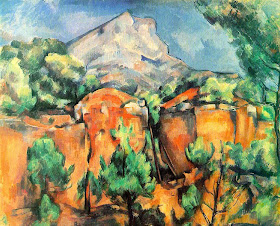

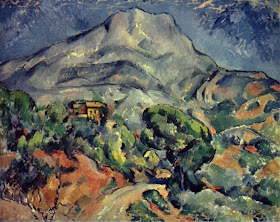

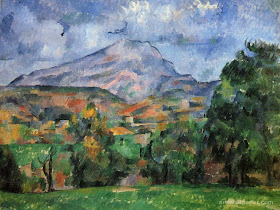

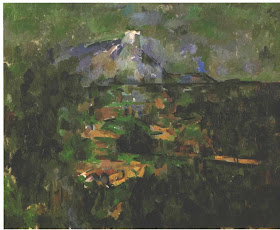

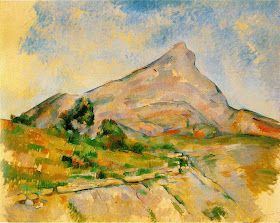

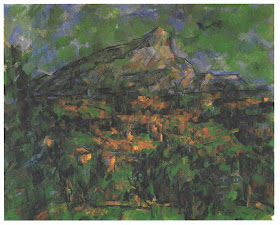

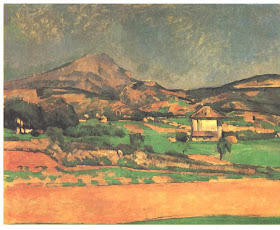

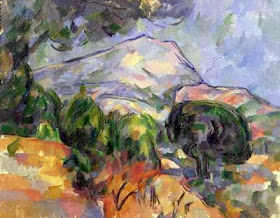

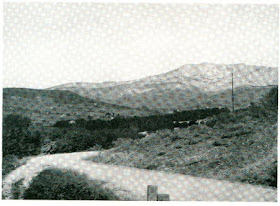

The following are just a few of Cézanne's renditions of Mont Sainte-Victore. [He is said to have painted it 88 times.] Note the color patches.

What we might notice is that indeed it is as though the geological givens of the mountain undergo a conversion through Cézanne's painting. Color impressions in a way have taken the place of geometrical structures. The frame and the sensations seem to have intertwined. It is a "reassembly" of the mountain, as Charles Write puts it:

"I have my motif," Cézanne said, speaking of Mt. S. Victoire. And I have mine – the architecture of the poem, the landscape of the word. Cézanne meant the reassembly of S. Victoire. I mean the same thing. (Wright 33-34)

Maxson J. McDowell notes how Cézanne alters the mountain's appearance: "Cézanne distorted the motif to make his painted planes relate to the overall plane of the flat canvas" (McDowell).

Pavel Machotka notes a similar transformation.

It is perhaps the interplay between Cézanne's close attention to the motif and his power of synthesis that strikes the deepest chord. The structure of the solid forms is defined by the motif, while the treatment of the surfaces is shaped, again, by Cézanne's compositional purpose. (Machotka)

We later will consider such transformations as modulation. Yet it is accomplished through the action of the diagram. Deleuze writes:

The diagram is indeed a chaos, a catastrophe, but it is also a germ of order or rhythm. It is a violent chaos in relation to the figurative givens, but it is a germ of rhythm in relation to the new order of the painting. As Bacon says, it "unlocks areas of sensation." [ft.7] The diagram ends the preparatory work and begins the act of painting. There is no painter who has not had this experience of the chaos-germ, where he or she no longer sees anything and risks foundering: the collapse of visual coordinates. [...] It is a kind of experience that is constantly renewed by the most diverse painters: Cézanne's "abyss" or "catastrophe," and the chance that this abyss will give way to rhythm; Paul Klee's "chaos," the vanishing "gray point," and the chance that this gray point will "leap over itself" and unlock dimensions of sensation. (Deleuze 72bc)

In the above Cézanne paintings, we might notice that there is a coherence and orderliness to the original photograph and as well a coherence and orderliness to the resulting paining. Yet they are two different 'logics' if you will. The parts are different, and so too are the relations between those parts. Before I suggested a clarification of what Deleuze might mean by chaos. I offer one now for rhythm.

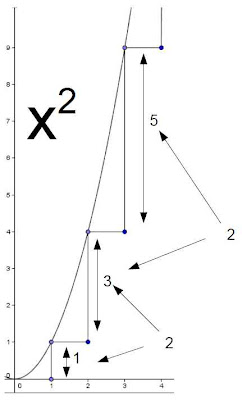

To do so, I will draw from his writings on Spinoza & rhythm. We in the first place conceive of differences without terms. We find them in differential calculus. The terms diminish to the infinitely small. So they have vanished. But the relations between them remained. Deleuze refers us to Leibniz' triangle demonstration to help us conceive this. Look at how the sides of the smaller triangle diminish to the infinitely small. Yet, their ratio is maintained in the proportions of the larger triangle.

So in this way we have differential relations without terms, just a pure relation of difference. Deleuze has us understand the body as being made of differential relations between infinitely small parts. The quantitative value of the differential relation tells us the power of the body these parts make-up. This power is how much the body is affecting another body and being affected by it. If two bodies make shocking impact, and they maintain their differences while also maintaining their differential relation, then the bodies were powerful enough to withstand the affection. So if arsenic enters our blood, but our blood does fine with the presence of the arsenic, then the blood had a strong power. And if the blood can eliminate the arsenic, then the blood was more powerful. But any time there is a composite, it is on the basis of a sustained differential relation. And all bodies are composite.

When bodies impact one another, they will send shock-waves of differentiation through one another. In the case of the arsenic, if enough is placed in the blood, this will send shockwaves that disrupt the differential relations between the parts of the blood, perhaps decomposing the blood. This sends shockwaves to the other organs depending on the integrity of the blood. This reaches even the person's imagination, who begins to foresee her death. These shock waves are waves of affection, and they are differential variations, that is, continuous waves of affective variation. As continuous variation, they too are like calculus differentials. So consider this animation below (created by Fayetteville State University Department of Mathematics and Computer Science). When the triangle is big, the red line tells us on average where the curve is heading in that region enclosed in the lines. Then, we diminish the x and y values to the infinitely small. Even though the values have vanished from finite extension, they still maintain their ratio. This ratio is like the 'rise-over-run' values of the red line. So the red line, now a tangent, tells us where the curve is headed at that particular place where the infinitely small values are related. If this curve were telling us the acceleration of an object moving in a straight line, then it would give us the 'instantaneous velocity'.

Previously we discussed the differential shock-waves of affection communicated between bodies when they make contact and differentially relate to one another. The variations in those shock-waves is like a curve, and at any moment it has a value of instantaneous change. This would be the tendency for the object's power-value to change at a given moment. So not only are there values for the body's level of power, there are also values for how much that level is tending to change at some moment.

What Deleuze calls rhythm is the self-affective adaptation to other bodies' trying/tending to change us. His example is when we jump in the water, making impact with a wave. The wave will try to influence our body, pushing it away perhaps, and the shock of this contact will send waves of affection throughout our body, for example, it might change our heart rate and breathing. But a good swimmer will know how to adjust her body so to swim with the wave. She does not destroy the wave, she himself is not destroyed, and she and the wave are not assimilated into one homogeneous thing. Rather, they maintain their differential relation. This is only possible because the swimmer made changes in her own body, like with physical positioning and breathing patterns. And for her to have made these changes, that required she send waves of variation throughout her own body. So the 'adjustment' is really internally differentiating oneself within oneself, changing the differential relations of the internal simplest bodies (the smallest parts). This is so that these simplest bodies may then maintain a differential relation with the wave, which results in swimming. Now, this knowing how to internally differentiate oneself so to differentially relate with other things Deleuze calls having a sense of rhythm. So rhythm must be the way bodies differentially relate and how modifications or modulations in those relations can either sustain or break-down the relations between bodies. If we can feel the rhythm of sensation or affection, then we know how to ride the wave. Another of Deleuze's examples is getting on the dance floor. We will have to modify our body's workings in order both to stay with the other dancers all while expressing our individual dancing style. And Deleuze offers a musical illustration as well. Consider a violin and a piano playing with one another. One piano is responding to the violin all while the violin responds to the piano. It is like a continuous simultaneity of response, in other words, a continuously varying differential relation, which Deleuze calls rhythm. So again, rhythm in this case is not a repeating pattern. I suggest we should not read Deleuze's concept of rhythm with those connotations. Rather, rhythm is something that can be found in an instant between simultaneously differentially related bodies. It is this relation tending toward co-responsive variations. Feeling the rhythm of sensation means 'being in the moment' of a dance with the world on the basis of us standing out from the world.

Let's return to Cézanne. Recall his 'diagram'. This is his sense-contact with the world, which renders his motif in its many variations. We might say that the original imagery passes through chaos, as if it were subject to random variations. But we need not think that Deleuze's chaos is necessarily about randomness. When the diver hits the wave, there is a chaos of sorts. It is like the piano and the violin both simultaneously responding to one another, both at the same time internally differentiating in response to each other. Consider when Cézanne opens his sensation channels to receive the full variations of the world around him. This means he allows his own body to be affected but also to respond with its own variations. These variations are like his swimming, dancing, or musically-performing with variations in the world impacting him and affecting him. The result of this is a reorganization of the world's variations into the variations of his painting. What he paints is how he was differentially affected. So it is more than just painting what he sees as a way to depicting his impressions. Rather, he is painting the way he was affected by his motif along with the way his body differentially reorganized so to maintain his differential relation. Keeping the sense channels fully open to the absolute variation of the world around us is probably difficult to maintain, given how it disorients us so much; so for Cézanne to maintain that state, he would have needed an excellent sense of rhythm, that is, the ability to change himself internally so to maintain his differential relation with the pure variations of the world around him.

So with these refined notions of rhythm, chaos, and diagram, we will turn to notions of digital and analog before reaching the concept of aesthetic analogy.

Analog and Digital Painting

We begin with a problem. When a painting is overly representational, then our minds see things they already know, and can summarize them verbally, which reduces the aesthetic experience with the work. If we see a painting of a bird landing on field, we recognize the bird, which takes little imagination, and we can sum it up as "its a landing bird" and then move on to the next painting. But if instead the painter wanted the viewer to feel some sensations and be held in them, representations that tell stories will not always suffice. Deleuze describes first two approaches of avoiding narratively representational figurations: abstract painting and action painting (abstract expressionism).

We may think of abstract painting as being 'digital'. Consider first when we count to five on our hands. Our fingers of course, are also called 'digits'. It does not matter how far we spread our fingers apart. They will still represent the number five. This is because we established oppositional relations that clearly demarcate the values. The first finger is absolutely different from the space spanning between it and the second finger. And the first finger and the second are as well clearly set in opposition to one another. This would not be the case if we were measuring the total span of our fingers from end to end. In that case, the quantity would not involve such discrete parts. It would not matter whether or not the fingers were touching or spread as far as possible. But when we count on our fingers, we establish binary relations between discrete parts. This is the basis for digital in all its varieties.

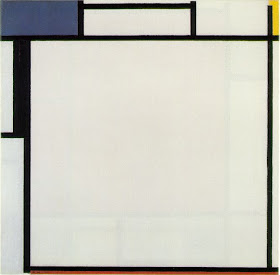

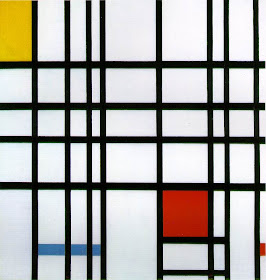

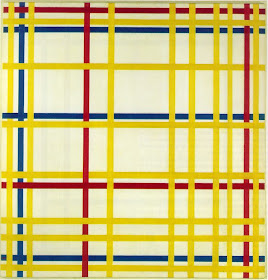

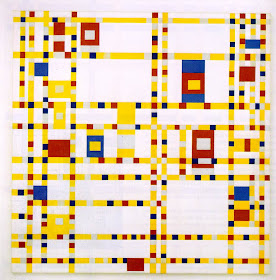

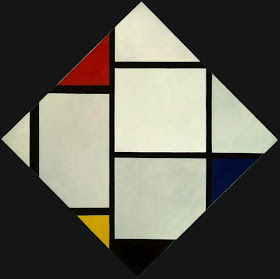

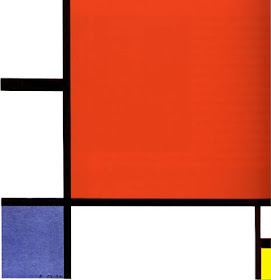

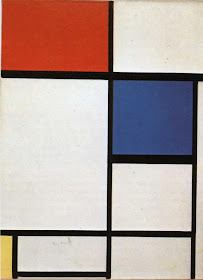

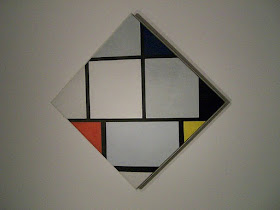

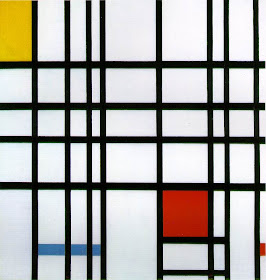

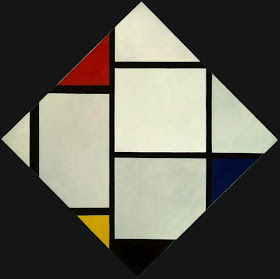

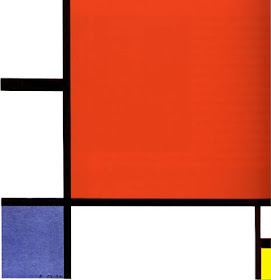

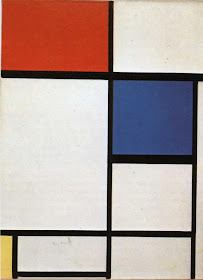

Abstract painting will deal with parts of the painting as being discretely divisible (often into sharply defined geometrical figures), with these parts being set into oppositional relations that carry with them some coded effect. First consider Piet Mondrian.

Mondrian.Composition with Blue, Yellow, Black, and Red, 1922

(Thanks artchive)

Mondrian. Composition with Yellow, Blue and Red, 1937-1942

(Thanks artchive)

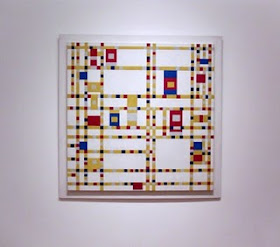

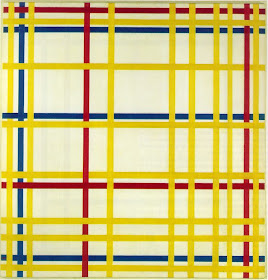

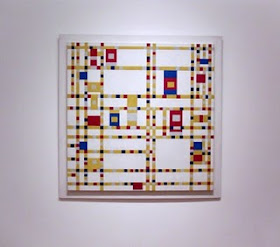

Mondrian. New York City, 1941-1942

(Thanks artchive)

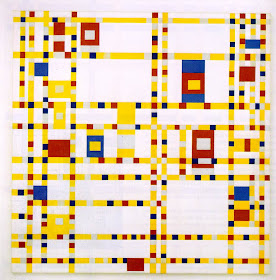

Mondrian. Broadway Boogie Woogie 1942-1943

(Thanks B)

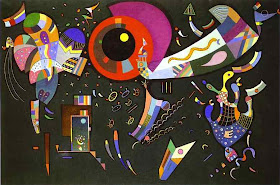

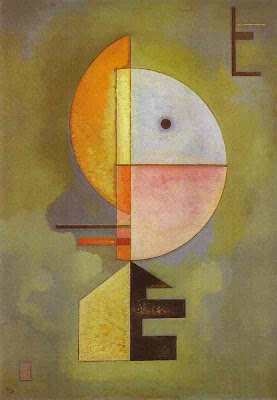

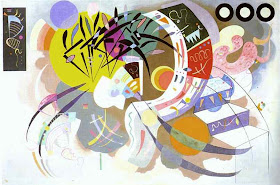

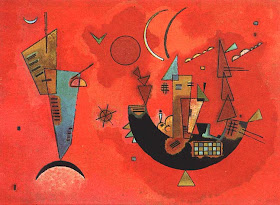

And consider also Wassily Kandinsky.

Kandinsky. On White II, 1923

(Thanks Webmuseum, Paris)

Kandinsky. Composition VIII , 1923

(Thanks Webmuseum, Paris)

Kandinsky. Black and Violet , 1923

(Thanks Webmuseum, Paris)

Kandinsky. Transverse Line , 1923

(Thanks Artchive)

Kandinsky. The White Dot

(Thanks NZ Fine Prints. Print of this painting sold there.)

Here is a clip showing Kandinsky painting.

We see then that there are discrete elements set in opposition to one another, rather than blurring or blending together continuously. This is like the discreteness of our fingers counted as digits. But also it seems that none of the images represent anything else. Nonetheless, Deleuze still sees coding in the digital component of abstract art. It has to do with how the oppositional relations between the parts of the painting affect us. It also involves the values already found in the spatial locations of the canvass (perhaps for example we might think of how images in the center of the canvass have more importance.) Some abstract painters formalized and articulated the way their paintings are 'coded' on the basis of placement and relation of the painting's discrete parts. Deleuze writes that this coding is something like computation; it involves calculating values to produce the desired affect, all without any representations. As Deleuze puts it, abstract art uses the fingers in the sense of the fingers that count.

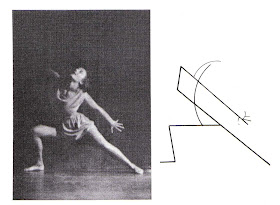

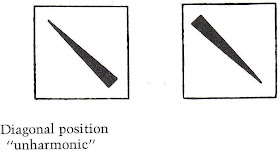

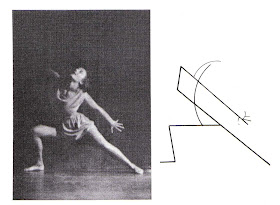

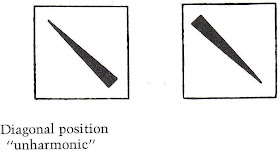

Consider first the isolation of discrete parts of this dancer's form, and the way the angles of these parts produce a certain feeling in the image, in this case, unharmonic:

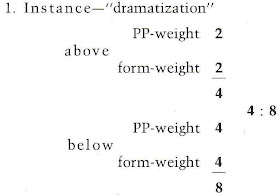

(From Kandinsky, Writings, p.520)

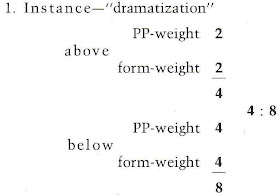

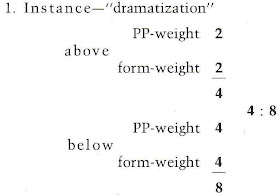

Perhaps in Kandinsky's paintings we might see something like the linear version of the dancer, without us seeing a dancer. But what we still might sense is the affect that the relations of its lines have on us. So there is coding without representation. There is also calculation. Consider this chart which calculates the distribution of tonal weight (darkness) between distinct parts of the canvass. Different affects will result from different numerical outcomes. So here we see that the painter's hand was not so much touching and putting itself into the paint as much as it was standing back and counting values in the service of the eye.

(From Kandinsky, Writings, p.665)

Thus the digital element in painting can be characterized by a subordination of the hand to the eye and discretely opposed parts that are coded for affect. Now let's see how the concept of diagram applies here. The diagram as we saw was what caused the painting's parts to differentially relate among themselves and for us to differentially relate with the painting's parts. Recall again our concrete example of the diagram in a painting.

Both the coding and this diagram here cause the parts to differentially relate. In this case of Van Gogh, the differential relations are created by the direct impact that the bendings have on the shape and apparent motion of the painting's parts. This is a visual impact. But we see it is not merely visual. The differential forces are acting directly on the strokes to cause them to want to move around, which results in our visually sensing them moving. However, the coding in abstract painting does not involve the coded parts differentially relating by means of contact of their differential forces. It is rather by means of binary relations that we interpret between discretely separate parts. So we can say that one property of the diagram is that it directly touches the painting's parts, and adds forces to them which cause them to tend to go in certain directions.

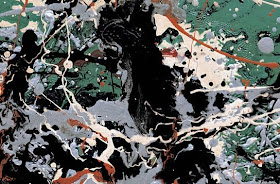

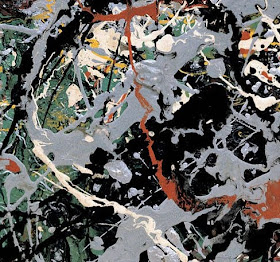

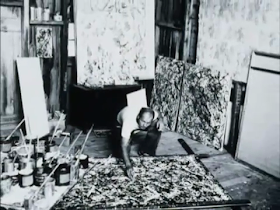

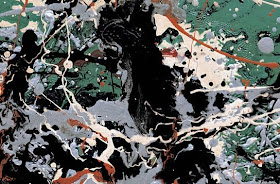

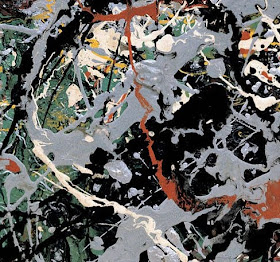

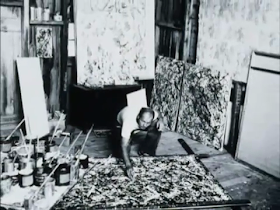

What if the diagrammatic influence touched every single stroke of the painting? What would result is action painting, also called abstract expressionism and art informel. Here we see the direct influence of the hand in its rawest physical motions. It touches every single part of the painting. With the optical geometry of the digital abstract painting, we can see clear outlines that divide the painting's parts, and our eyes can follow those lines without much difficulty. But try to follow the lines in Jackson Pollock's works.

Pollock. Untitled. Green and Silver

(Thanks Worthpoint)

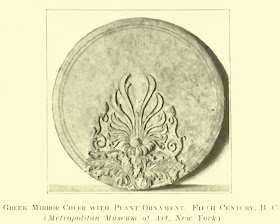

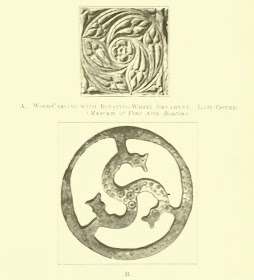

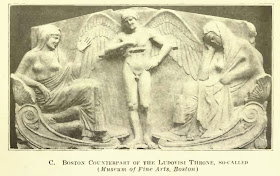

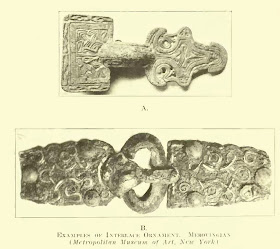

In action painting, the lines are what Worringer calls the Northern Line or the Gothic Line. We first consider the "organically tinged ornament" of Classical Lines (Worringer 47b.d).

Classical ornament has organic clearness and moderation, and it seems to spring "without restraint from our sense of vitality." And also, "It has no expression beyond that which we give it" (48b). But now consider the Northern Lines of Gothic ornament.

Northern ornament, he says, seems to take on a life all its own, and in fact seems to act upon us ourselves.

The expression of northern ornament, on the other hand, is not immediately dependent upon us; here we face, rather, a life that seems to be independent of us, that makes exactions upon us and forces upon us an activity that we submit to only against our will. In short, the northern line is not alive because of an impression that we voluntarily impute to it, but it seems to have an inherent expression which is stronger than our life. (48bc, boldface mine)

We might say that the northern line is produced by the hand's own free self expression. It is not like drawing a line or curve with controlled movements. This we would see in digital abstract art. It is also the product of an organicism in the movements of our hand's parts and in the parts of the smooth controlled line that we draw. "The movement we make is of an unobstructed facility; the impulse once given, movement goes on without effort," he writes (48d). This pleasant feeling is a "freedom of creation," and we transfer it

involuntarily to the line itself, and what we have felt in executing it we ascribe to it as expression. In this case, then, we see in the line the expression of organic beauty just because the execution corresponded with our organic sense. (48-49, boldface mine)

But consider instead if we drew our line out of nervous agitation. We are constantly in defiance of what we just did in order to be as irregular as possible.

If we are filled with a strong inward excitement that we may express only on paper, the line scrawls will take an entirely different turn. The will of our wrist will not be consulted at all, but the pencil will travel wildly and impetuously over the paper, and instead of the beautiful, round, organically tempered curves, there will result a stiff, angular, repeatedly interrupted, jagged line of strongest expressive force. It is not the wrist that spontaneously creates the line; but it is our impetuous desire for expression which imperiously prescribes the wrist's movement. The impulse once given, the movement is not allowed to run its course along its natural direction, but it is again and again over whelmed by new impulses. When we become conscious of such an excited line, we inwardly follow out involuntarily the process of its execution, too. (49b.d, boldface mine)

But when we follow someone else's wild line, we do not feel pleasure. It seems more like "an outside dominant will coerced us" (49cd). What we feel seems like the forces of the ruptures in the line's incoherent discontinuity.

We are made aware of all the suppressions of natural movement. We feel at every point of rupture, at every change in direction, how the forces, suddenly checked in their natural course, are blocked, how after this moment of blockade they go over into a new direction of movement with a momentum augmented by the obstruction. The more frequent the breaks and the more obstructions thrown in, the more powerful becomes the seething at the individual interruptions, the more forceful becomes each time the surging in the new direction, the more mighty and irresistible becomes, in other words, the expression of the line. (49-50, boldface mine)

So consider when we were drawing the curved line. We felt physically a pleasure on account of there being no obstructions breaking the flow of our hand's movements. The parts of our wrist worked together to create a line that is self-consistent in its curving motion. With the erratic line, however, there seems to be unpredictable forces which break the flow, in fact prevent one from starting, and prevent any possibility of there being coherence in the motions or the line. Our hands drawing calmly seem to do so merely by means of our bodies acting automatically and with coordination among its parts. So when it is erratic, that suggests to us the forces causing the unpredictabilities do not come from the body, but rather from some psychic or spiritual source.

The essence of this inherent expression of the line is that it does not stand for sensuous and organic values, but for values of an unsensuous, that is, spiritual sort. No activity of organic will is expressed by it, but activity of psychical and spiritual will, which is still far from all union and agreement with the complexes of organic feeling. (50b, boldface mine)

Worringer clarifies that Gothic ornament and such a scrambled line made by an emotionally or mentally excited person are not at all the same things. However, Worringer will compare them to clarify what he means by the northern line. He says for example that the lines of northern cultures tell us that they were

longing to be absorbed in an unnatural intensified activity of a non-sensuous, spiritual sort one should remember in this connection the labyrinthic scholastic thinking in order to get free, in this exaltation, from the pressing sense of the constraint of actuality. (50d, boldface mine)

Now, notice how classical ornament exhibits symmetry.

However Gothic does not. But instead of symmetry, repetition is predominant. (52ab) Classical has repetition too, but like a mirroring. The repetitions have the "calm character of addition that never mars the symmetry" (52bc).

Gothic repetition, however, is more like a repetition of difference striving to rise to the nth power.

In the case of northern ornament, on the other hand, the repetition does not have this quiet character of addition, but has, so to speak, the character of multiplication. No desire for organic moderation and rest intervenes here. A constantly increasing activity without pauses and accents arises, and the repetition has only the one intention of raising the given motive to the power of infinity. The infinite melody of line hovers before the vision of northern man in his ornament, that infinite line which does not delight but stupefies and compels us to yield to it without resistance. If we close our eyes after looking at northern ornament, there remains only the echoing impression of incorporeal endless activity. (52-53, boldface mine)

Worringer then cites work from Lamprecht where he describes the labyrinthine nature of the Gothic lines.

Lamprecht speaks of the enigma of this northern intertwining band ornament, which one likes to puzzle over [PI. VIII]. But it is more than enigmatic; it is labyrinthic. It seems to have no beginning and no end, and especially no center; all those possibilities of orientation for organically adjusted feeling are lacking. We find no point where we can start in, no point where we can pause. Within this infinite activity every point is equivalent and all together are insignificant compared with the agitation reproduced by them. (53a.b, boldface mine)

As Deleuze puts it, the Gothic Line "does not go from one point to another, but passes between points, continually changing direction, and attains a power greater than 1, becoming adequate to the entire surface" (

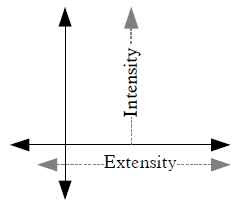

Francis Bacon, 74ab). Let's explore a possible explanation for the line having a power greater than one (and we build again from this entry on Spinoza & rhythm). We first should explore some of Oresme's concepts that Deleuze refers us to. [For his discussions of Oresme, see Deleuze's Expressionism in Philosophy Ch 12 and his Cours Vincennes 10/03/1981]. Oresme invented a way to represent the intensities of qualities. We would now consider this to be variations between the x and y axis. Oresme called them longitude and latitude.

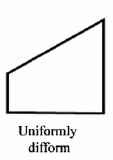

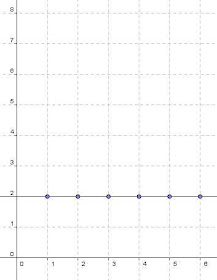

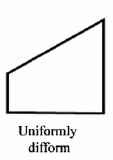

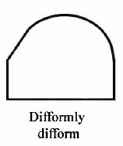

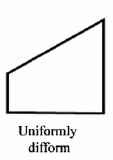

Consider if we plotted motion for example, with time as the x-axis and speed as the y-axis. And suppose that the object continues going at the same rate of motion. This will have its own 'form'. It will be like a rectangle, because there is no change in the intensity of the speed. Oresme calls this uniformity in intensity the latitudino uniformis.

(Thanks Jeff Babb)

Non-uniform rates of change, latitudo difformis, would be ones such as constant acceleration. Because the magnitude of intensity increases, we would figure it with a triangle or sloping straight line (Oresme 247B.c):

(Thanks Jeff Babb)

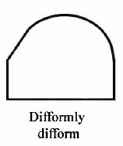

All other forms are ones whose non-uniform rate of change itself is not uniform. These are latitudo difformiter difformis, as for example an irregularly-paced rate of acceleration, which is always the case in the physical world. Oresme says of the difformly difform quality that “it can be described negatively as a quality which is not equally intense in all parts of the subject nor in which, when any three points of it are taken, the ratio of the excess of the first over the second to the excess of the second over the third is equal to the ratio of their distances.” Hence, if the latitudinal line is not smoothly straight, then it is difformly difformed. Latitudo difformiter difformis is “imaginable by means of figures otherwise disposed according to manifold variation (Oresme 248A.a; B.d):”

(Thanks Jeff Babb)

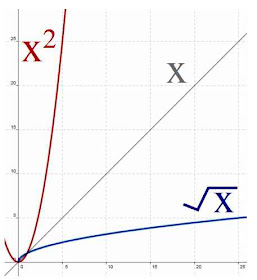

So to better understand why the Northern Line has a power greater than one, we will look to when Deleuze refers us to a concept of depotentialization, which he very well might have drawn from Hegel's calculus writings in the Science of Logic (especially§§569-570). Consider the graph below. If we just have y = x, then we just have a straight line, and not a curve.

But when we have y = x squared or y = the square root of x, then we have curves. What seems to allow for the function's line to curve is that there is a difference of power between them. In the case of y = x, they both tug on each other about the same amount throughout their variations. But in y = x squared, it is as though y pulls more-and-more on x as x increases, which is why the curve rapidly tilts upwards. So we might think of y having an increasing power, or having power of a higher order. For each standard unit of increase of y, it has an increased influence on x, and the magnitude of that influence itself increases with each unit. Deleuze refers to this as an acceleration. We will need to use this metaphorically to extract an idea we later use: we can only find the power relations on a variation if our line is curved, and we can only have a curved line if x and y have different powers in relation to one another.

Hegel writes of these values that "they are — or at least one of them is present in the equation in a higher power than the first” (Hegel, Science of Logic §613).

We can really think of this as a power struggle between the variables. Let's see why. Hegel continues.

at least one of those variables (or even all of them), is found in a power higher than the first; and here again it is a matter of indifference whether they are all of the same higher power or are of unequal powers; their specific indeterminateness which they have here consists solely in this, that in such a relation of powers they are functions of one another. (Hegel, Science of Logic §615, boldface mine).

power is taken as being within itself a relation or a system of relations. We said above that power is number which has reached the stage where it determines its own alteration, where its moments of unit and amount are identical — as previously shown, completely identical first in the square, formally (which makes no difference here) in higher powers. (Hegel, Science of Logic §615, boldface mine).

Let's consider first the function y = 2 which means that there is no relation of variance with x, so this is like Oresme's uniform motion:

(Thanks Jeff Babb)

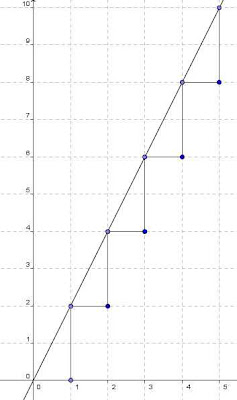

Now we will consider the value for y = 2x:

Here we see that there is a relation of variance between x and y. As x increases, y increases doubly, but uniformly so; y is always twice x, so they are on the same level or power. This is like Oresme's uniformly difform motion.

(Thanks Jeff Babb)

Hegel says that there is no reason to differentiate a point on such a line, because it would be the same ratio as the line itself. Now we will consider the graph for x squared:

Here we see that the y value is not twice the x. This is because the y and the x do not relate to each other, rather the y relates only to the x squared. This is like Oresme's difformly difform motion.

(Thanks Jeff Babb)

In the x-squared diagram, we see that there is a continuous disproportioning of the relation between y and x, a continuous difforming that continuously doubles.

So we see that when one of the variables attains a power higher than one, there is a power struggle between the variations of the variables. It causes a change in the change, that is, a difformly difform variation. The Gothic Line is like this too. It has forces of different levels of power pushing and pulling it in a way that deforms it. Let's look closer at Pollock's lines to see this.

Pollock. Untitled. Green and Silver

(Thanks Worthpoint)

Pollock. Untitled. Green and Silver, details

(Thanks about.com / Shelley Esaak)

Pollock. Full Fathom Five

Pollock. Full Fathom Five, detail

(Thanks ibiblio)

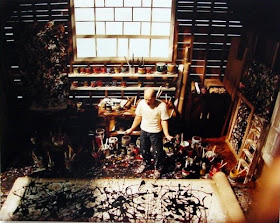

What we see is not so much his eyes telling his hands what to do. Rather, it is his hands doing what they want to do. See how directly his hands are involved in the paint splatters, how his hands show themselves in the results.

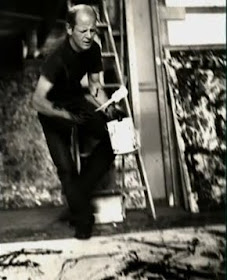

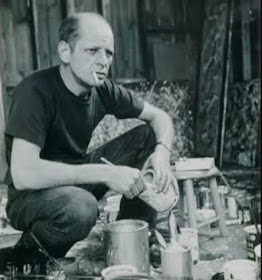

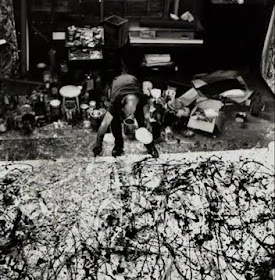

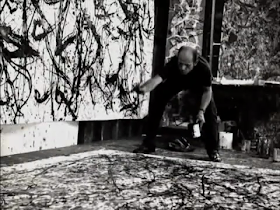

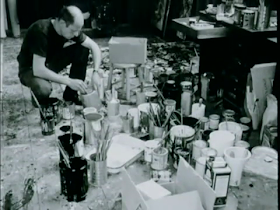

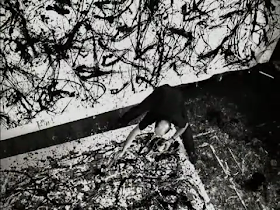

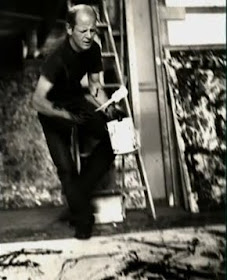

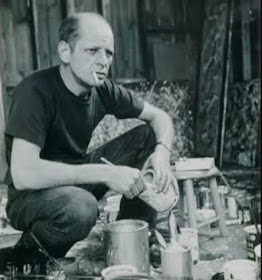

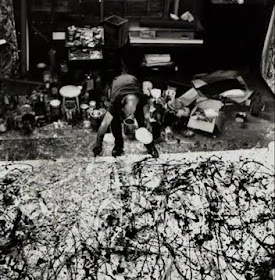

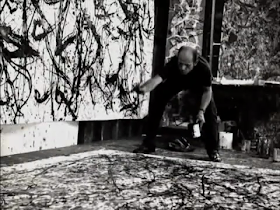

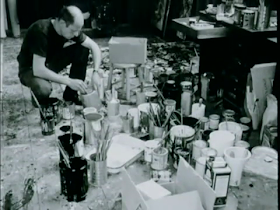

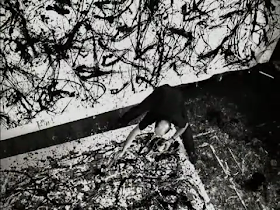

Jackson Pollock painting

(Thanks Biography Channel)

Jackson Pollock painting

(Thanks Biography Channel)

Jackson Pollock painting

(Thanks Biography Channel)

Jackson Pollock painting

(Thanks Biography Channel)

Jackson Pollock painting

(Thanks Biography Channel)

Jackson Pollock painting

(Thanks Biography Channel)

Jackson Pollock painting

(Thanks Biography Channel)

Jackson Pollock painting

(Thanks Biography Channel)

Jackson Pollock painting

(Thanks Biography Channel)

Jackson Pollock painting

(Thanks Biography Channel)

Jackson Pollock painting

(Thanks Biography Channel)

Jackson Pollock painting

(Thanks Biography Channel)

Jackson Pollock painting

(Thanks Biography Channel)

In this clip we learn more about Pollock's drip techniques.

Jackson Pollock, his drip style, From Biography Channel

(Thanks Biography Channel/A&E)

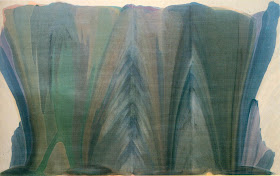

Deleuze says we see this Gothic Line in Morris Louis's stains.

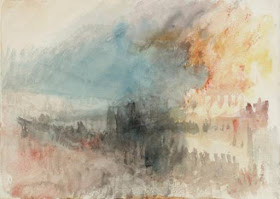

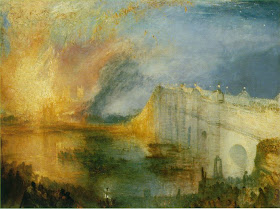

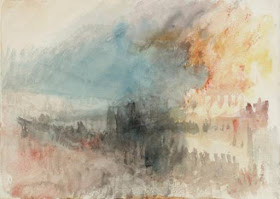

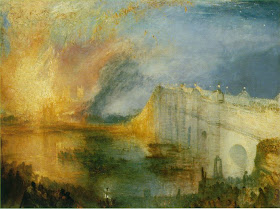

And Turner's later watercolors exhibit "the power of an explosive line without outline or contour, which makes the painting itself an unparalleled catastrophe" (74bc).

Turner. Oberwesel 1940

(Thanks watercolorblog.artistsnetwork.com)

Turner. The Burning of the Houses of Parliament, 1834

(Thanks nga.gov)

Turner. The Burning of the Houses of Parliament 1834

(Thanks tate.org.uk)

Turner. The Burning of the Houses of Parliament 1834

(Thanks tate.org.uk)

Turner. The Burning of the Houses of Parliament 1834

(Thanks tate.org.uk)

Turner 1775-1851 The Burning of the Houses of Parliament, from the River 1834

(Thanks tate.org.uk)

Turner 1775-1851 The Burning of the Houses of Parliament, from the River 1834

(Thanks tate.org.uk)

Turner Colour Study: The Burning of the Houses of Parliament 1834

(Thanks tate.org.uk)

Turner Colour Study: The Burning of the Houses of Parliament 1834

(Thanks tate.org.uk)

The Burning of the Houses of Parliament, with Westminster Bridge 1834

(Thanks tate.org.uk)

or

Turner. The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons 1835

(Thanks wikimedia.org)Turner. Off Ramsgate 1940

(Thanks thedrawingsite.com)

Turner. Sky and Sea c. 1826-9

(Thanks thedrawingsite.com)

Turner. Light and Color – Moses Writing the Book of Genesis

or

Light and Color (Goethe's Theory) - the Morning after the Deluge, exhibited 1843.

(Thanks arthistory.about.com)

(Thanks brooklynrail.org)

Turner. The Burning of the Houses of Parliament

(Thanks wikimedia.org)

Turner. Moonlight 1940

(Thanks terminartors.com)

Deleuze notes that even in Kandinsky we can find "nomadic lines without contour next to abstract geometric lines" (74c).

Even in Mondrian we can find the Gothic Line in way implied in our eye motions between the straight geometrical lines: "in Mondrian, the unequal thickness of the two sides of the square opened up a virtual diagonal without contours" (74c).

Mondrian. Composition II with Black Lines. Compositie nr.2 met swarte lijnen 1930

(Thanks Olga's Gallery)

Mondrian. Opposition of Lines, Red and Yellow. 1937

(Thanks timesonline)

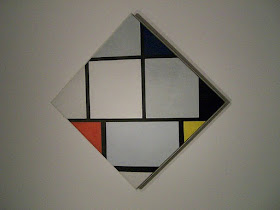

Mondrian. One of The Diamond Compositions

(Thanks National Gallery of Art)

Mondrian. Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow 1930

(Thanks Southern Baker)

Piet Mondrian. Composition with Blue, Red and Yellow - Compositie met blauw,rood en geel 1930

(Thanks Olga's Gallery)

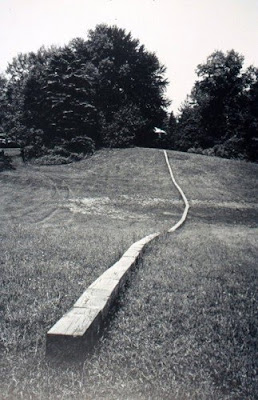

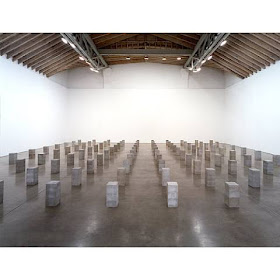

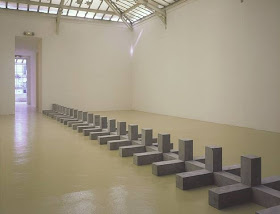

But Pollock goes even further in decomposing the formation by means of the raw manual influences producing Gothic lines. On account of the diagrammatic push-and-pull forces of these lines, Pollock's painting "becomes a catastrophe-painting and a diagram-painting at one and the same time" (74cd). And it is also in this sort of painting that "modern man discovers rhythm" (74d). Why? In this sort of painting, the hand does not make use of formulaic ways to apply the paint. Rhythm we said was like when the swimmer must alter his own inner differences so to maintain a differential relation to the inner differences of the wave he swims through. And rhythm is like when a violin and piano must improvise together, each one responding to the other simultaneously. The hand works with the paint like it were a wave or another musician. The hand does not control the paint as much as it differentially relates itself with it. The hand must continually change what it does in order to handle those aspects of the paint which it leaves unmastered, unmanipulated. "The hand is liberated, and makes use of sticks, sponges, rags, syringes: action painting, the 'frenetic dance' of the painter around the painting, or rather in the painting, which is no longer stretched on an easel but nailed, unstretched, to the ground" (74-75). Deleuze also goes on to cite examples of how abstract expressionism developed after Pollock. It became "the elaboration of lines that are 'more' than lines, surfaces that are 'more' than surface, or, conversely, volumes that are 'less' than volumes (Carl André's planar sculptures, Robert Ryman's fibers, Martin Barré's laminated works, Christian Bonnefoi's strata)" (75a).

Now, even Mondrian's paintings defy the easel in a way, because they do not limit themselves to the boundaries of the outer frame. When hung on the wall, we come to see the patterns as extending outside the painting to relate to other parts of the wall. "In an abstraction of Mondrian's type, the painting ceases to be an organism or an isolated organization in order to become a division of its own surface, which must create its own relations with the divisions of the "room" in which it will be hung. In this sense, Mondrian's painting is not decorative but architectonic, and abandons the easel in order to become mural painting" (76b, boldface mine).

Mondrian. Gallery Wall 1

(Thanks doomlaser.com)

Mondrian. Broadway Boogie Woogie gallery wall.

(Thanks Mathew Beall)

Mondrian. gallery wall

(Thanks Mathew Beall)

Mondrian. Gallery Wall

(Thanks Mathew Beall)

Mondrian. Victory Boogie-Woogie gallery wall

(Thanks Holland.com)

Mondrian. gallery wall

(Thanks Allie)

Mondrian. Tableau No. IV; Lozenge Compostion with Red, Gray, Blue, Yellow and Black gallery wall

(Thanks Gilbert Musings)

But Pollock defies the easel in another way. Recall Kandinsky's formulas.

(From Kandinsky, Writings, p.665)

We see that certain sorts of things should go in certain places on the canvas. This means it is more probable to find certain things in their more proper locations. Also just think of how in general, the more important parts of the image are placed near the center of the canvass rather than at the edges or even slipping off the edges. However, look again at Jackson Pollock painting.

We see that he splatters the paint across the outer boundaries of the painting. For this reason, no part of the canvass is a preferred spot for certain contents. It is equally probable for some splatter to be found anywhere on the canvas, including sliding off from it or even falling outside it.

We will now look at analog and digital ways to create resemblances.

Deleuze says that both the analogical and the digital modes produce resemblances that are analogous to what they are reproducing.

Now, recall what we said above about Peirce's diagram: the relations between its parts are analogous to the relations of the represented things parts, even though there may be no sensible resemblance between the two. We then noted a difference between Peirce's and Deleuze's diagrams. In Deleuze's diagram, there is a sensible resemblance, but the relations between the parts are not analogous. For Peirce it is the inverse: there is no sensible resemblance, but the relations between the parts are analogous.

Deleuze says that digital reproduction produces an analogy by means of isomorphism. Let's walk through his explanation, using an example, to get a more precise understanding of what he means by isomorphism.

Recall Peirce's three types of signs: icons, indices, and symbols. Icons resemble their referent (a drawn pencil line resembles a geometrical line); Indices have a dynamic relation with their referent, in some cases by leaving an imprint of the one in the other (a bullet hole in a wooden moulding is a sign for the gun shot that made the hole); and Symbols represent their object by mans of a conventional rule or a habit.

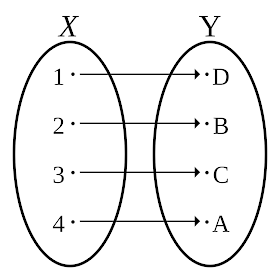

We will now look at what makes an isomorphism, first in a somewhat technical manner. Consider two sets:

Set X's members: 1, 2, 3, 4

Set Y's members: A, B, C, D

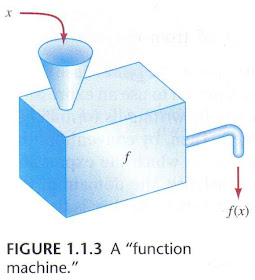

We will then say that there is a function involved. Recall Edwards' & Penney's "Function Machine":

A function is like a machine that takes-in one value and gives-out another. In the case of our isomorphism, we will say that there is a function that takes-in members of the first set, and gives-out members of the other set. If we take-in '1' and give out 'D', we would represent this as:

f(1) = D.

Let's make the other assignments.

f(1) = D

f(2) = B

f(3) = C

f(4) = A

Wikipedia nicely represents this pictorially as:

We see that the assignments are arbitrary. We also notice that there is a one-to-one correspondence between the elements of the sets (Landsberg 58).

This then will help us understand how Deleuze means "analogy by isomorphism," when talking about digital coding. Let's take binary as an example of digital coding. There are two abstract elements, the one and the zero. [Perhaps they are abstract, because these numerals refer to discrete machine states, and thus the coding is something like an abstraction for the machine state; that is, its switches or whatever else are either in one or another position.]

Deleuze writes that we may "do at least three things with a code. One can make an intrinsic combination of abstract elements" (Deleuze 80c). So with our 1 and our 0, we may for example combine them to obtain:

0100100001100101011011000110110001101111

Deleuze continues, "One can also make a combination which will yield a 'message' or a 'narrative', that is, which will have an isomorphic relation to a referential set"(Deleuze 80c). So let's take our binary string as an example. We can for example break it into 8-bit parts.

01001000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111

Then, we can establish something like an isomorphic function to tell us how to convert these symbol-groups into letters. [Using the ASCII convention, we might say]

f(01001000) = H

f(01100101) = e

f(01101100) = l

f(01101100) = l

f(01101111) = o

[This example is taken from: docdroppers.org] In this way, our string "0100100001100101011011000110110001101111" can be converted into "Hello," on account of the isomorphism of the sets. In fact, the original string was composed intentionally for this translation. Deleuze then writes, "Finally, one can code the extrinsic elements in such a way that they would be reproduced in an autonomous manner by the intrinsic elements of the code (in portraits produced by a computer, for instance, and in every instance where one could speak of 'making a shorthand of figuration)' " (Deleuze 80c). The intrinsic elements seem in our case to be the 8-bit arrangements. And the extrinsic elements would be the letters. Computer software, running on the basis of binary codes, can automatically convert these binary sequences to the letters on our screens, just like how they convert the binary data of an image file to a picture we can see. So first we begin with "Hello" or some image. That is then converted to binary numerical codes for the letters or the homogenized square regions (pixels) of the image. The computer than by means of its own processes reproduces that original word or image, all mediated by the numerical code.

Notice how there is no resemblance between the letter formation and its isomorphic binary equivalent. And likewise with Deleuze's example, there is no resemblance between an image file's binary sequence and the image the software autonomously reproduces on our screen. Nonetheless, it is by means of this automatic reproduction that the resemblance to the original is produced, all through a medium, binary code, that bears no resemblance to the thing it codes and reproduces. But the thing it reproduces is similar to the thing that was originally rendered into code, so in a way the product is analogous to the original. Deleuze writes: "It seems, then, that a digital code covers certain forms of similitude or analogy: analogy by isomorphism, or analogy by produced resemblance" (80d).

Deleuze's point is that we cannot distinguish analog and digital by "saying that analogical language proceeds by resemblance, whereas the digital operates through code, convention, and combination of conventional units" (80c). This is because digital's isomorphism is analogous in a way, like Peirce's diagram. The isomorphic code preserves the relations between the original's parts, even though the isomorphism's parts do not resemble the original's parts.

But we will now consider pure analog reproductions. These make no use of code. Deleuze distinguishes two types. Consider first how when the resemblance is produced, there is some means by which it is done. If that means itself bears a likeness to what it reproduces, then 'resemblance is the producer.' In this case, the relations between the original's parts pass directly into its reproduced formation. Think for example of analog photography using film. The relations between the visual elements of the original image directly strike the chemical components of the film. Although it is in a negative form, the relations between the parts on the filmed image maintain the relations between parts of the original image, and this was all done on account of the original image directly affecting its medium. Now, it is true that there is a loss of fidelity in analog reproductions of this kind. But that does not change the fact that the result of this sort of reproduction is still a primary resemblance which allows for the reproduction to be taken as the likeness of the original. This will be more apparent when we contrast it to the next kind, which also involves an infidelity and resemblance.

Before we go on to resemblance as the product, Deleuze has us recall digital coding once again, because it almost fits this description. Recall how

0100100001100101011011000110110001101111

became

Hello

Notice in the first place how the number sequence bears no likeness to the word it produces (no likeness except for the isomorphic relation of its parts: H is to e as 01001000 is to 01100101, and so on). It is not like the Hello is some kind of imprint that we would expect from the number series. It rather seems like a 'brutal product' that is abruptly produced by the code. "resemblance is the product when it appears abruptly as the result of relations that are completely different from those it is supposed to reproduce: resemblance then emerges as the brutal product of nonresembling means. We have already seen an instance of this in one of the analogies of the code, in which the code reconstituted a resemblance as a function of its own internal elements" (81b). But the problem with coding is that the resemblance is already implied in the code. The last kind of reproduction has resemblance as the product, but unlike digital, no code is involved, and unlike analog, there is no primarily (formal and figurative) resemblance between the original and the reproduction. Some new appearance results with new relations between its parts. It is connected with the first only because a diagrammatic element modulates some part of the original so to produce something that does not formally resemble how it began, but our senses can feel that it is a deformation of the original. Any one part might 'sensibly resemble' the original part, but we see no clues that can help us trace it back the original form, so it is not a likeness. It just gives us a sensibly resembling sensation.

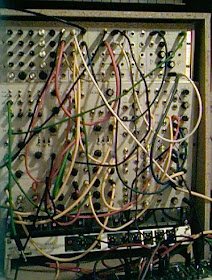

Deleuze will now explain analogical diagrams in terms of modulation, and he begins with the illustration of analog and digital synthesizers [For more on modulation and synthesizers, see this entry. And for more on the differences between analog and digital, see these entries here, especially this one here].

Analog synthesizers have different modules that affect the sound's properties in different ways.

In a sense, the sound signal is deformed by each module, as its properties are changed from its original form.

Digital synthesizers use integrated circuits, and they convert the sound wave to a homogenized form given a numerical code.

Integrated digital circuits do not process the electrical current as an analog of the sound wave, and it does not channel the flow from one module to another in the circuit. Rather, the wave is considered a quantity, and all the circuit's parts work together simultaneous to perform computational alterations to the code, so to produce the code for a modified wave.

Now let's return to Cézanne to better grasp this concept of modulation before moving to Francis Bacon. His motif was his incredible experience with the mountain he painted. He approaches the world as completely new, so that he may see its many nuances. In other worlds, he faces something purely different than anything he might expect. What he first sees arising from the field of pure variations are the geological structures. What he paints however are little color patches. He selects the colors that will produce in the viewer this feeling of having seen the mountain for the first time. We saw from the comparisons with the photographs of the mountain that there was a certain logic and coherence to the parts of the photographed mountain, but also a certain logic between the parts of the painting. But the painting's parts related more on the level of color sensations, and not formal elements.

Deleuze notes two sorts of modulation at work in Cézanne's painting. Notice first that Cézanne did not rely just on shading to portray depth. Instead he uses the oppositions of warm and cool tones, in some cases, to represent light and shadow or varying distances of objects (Turner 359).

Blue has no greater tone value than yellow when both are equally saturated, yet in certain contexts, when blue is painted next to yellow, it might suggest depth or volume (Conversations with Cézanne 191). To modulate the color would be for Cézanne to place a patch of one saturated color beside another, with their relation bringing about an effect determined not by some pre-set system but by the circumstances of their contextualization with the other color patches. (We can see in this Cézanne landscape below how the intense green on the horizon’s center recedes into the background. What is notable about this is that normally darkened colors seem like shadows and appear as though at a distance. Here we see that the intense green has not been darkened, and yet it colors the most distant place on the horizon).