[Search Blog Here. Index-tags are found on the bottom of the left column.]

[Central Entry Directory]

[Cinema Entry Directory]

[Filmmakers, Entry Directory]

[Vincente Minnelli, Entry Directory]

"if you think childlike, you'll stay young. If you keep your energy going, and do everything with a little flair, you're gunna stay young. But most people do things without energy, and they atrophy their mind as well as their body. you have to think young, you have to laugh a lot, and you have to have good feelings for everyone in the world, because if you don't, it's going to come inside, your own poison, and it's over" Jerry Lewis "I don’t believe in the irreversibility of situations" Deleuze

Corollary .— Individual things are nothing but modifications of the attributes of God, or modes by which the attributes of God are expressed in a fixed and definite manner. The proof appears from Prop. xv. and Def. v.

Corollary .— Individual things are nothing but modifications of the attributes of God, or modes by which the attributes of God are expressed in a fixed and definite manner. The proof appears from Prop. xv. and Def. v.Modes are, in their turn, expressive: “Whatever exists expresses the nature or essence of God in a certain and determinate way” (that is, in a certain mode). [ft.3: E I.36p [439] (and 25c: Modi quibus Dei attributa certo et determinato modo exprimuntur).] [Deleuze, 13-14; 352d]

Le mode, à son tour, est expressif : « Tout ce qui existe exprime la nature de Dieu, autrement dit son essence, d’une façon certaine et déterminée » (c’est-à-dire sous un mode défini). [ft.3 : E, I, 36, dem. (et 25, cor. : Modi quibus Dei attributa certo et determinato modo exprimuntur)] [Deleuze, 10-11; 11d]

God produces as he exists; necessarily existing, he produces. [ft.3: E I.25s: “God must be called the cause of all things in the same sense in which he is called the cause of himself”[431]. ] [Deleuze, 100b; 364a]

Dieu produit comme il existe ; existant nécessarement, il produit nécessairement [ft.3 : E, I, 25, sc. : « Au sens où Dieu est dit cause de soi, il doit être dit aussi cause de toutes choses. »] [Deleuze, 88b ; d]

According to Spinoza, God is cause of himself in no other sense than that in which he is cause of all things. Rather is he cause of all things in the same sense as cause of himself. [ft.20: E I.25s. It is odd that Lachièze-Rey, when citing this passage, inverts the order, as though Spinoza had said that God was cause of himself in the sense that he was cause of things. Such a transformation of the passage is not just an oversight, but amounts to the survival of an “analogical” perspective that begins with efficient causality (cf. Les Origines cartésiennes, pp.33-34] [Deleuze, 164a; 375a]

Selon Spinoza, Dieu n’est pas cause de soi en un autre sens que cause de toutes choses. Au contraire, il est cause de toutes choses au même sens que cause de soi [ft.20 : E, I, 25, sc. Il est curieux que P Lachièze-Rey, citant ce texte de Spinoza, en inverse l’ordre. Il fait comme si Spinoza avait dit que Dieu était cause de soi au sens où il était cause des choses. Dans la citation ainsi déformée, il n’y a pas un simple lapsus, mais la survivance d’une perspective « analogique », invoquant d’abord la causabilité efficiente. (CF. Les Origines cartésiennes du Dieu de Spinoza, pp.33-34).] [Deleuze, 149a ;d]

Modal essences therefore, no less than existing modes, have efficient causes. “God is the efficient cause, not only of the existence of things, but also of their essence.” [ft.7, citation] Deleuze, 193c]

C’est pourquoi les essences de modes n’ont pas moins une cause efficiente que les modes existants. « Dieu n’est pas seulement cause efficiente de l’existence des choses, mais encore de leur essence. » [ft.7, citation] [Deleuze, 175]

[from ft.8, Ch.12] The whole of I.24 appears, then, to me to be organized thus: 1. The essence of a thing produced is not cause of the thing’s existence (Proof); 2. But nor is it cause of its own existence as essence (Corollary); 3. Whence I.25, God is cause even of the essences of things. [Deleuze, 378-379]

[from ft.8, Ch.12] L’ensemble de I, 24, nous paraît donc s’organiser ainsi : 1°) l’essence d’une chose produite n’est pas cause de l’existence de la chose (démonstration) ; 2°) mais elle n’est pas davantage cause de sa propre existence en tant qu’essence (corollaire) ; 3°) d’où I, 25, Dieu est cause, même de l’essence des choses. [Deleuze, 176d]

An attribute expresses itself in three ways: in its absolute nature (its immediate infinite mode), as modified (its infinite mediate mode) and in a certain and determinate way (a finite existing mode). [ft.1: E I.21-25] [Deleuze, 235b; 385c]

Un attribut s’exprime de trios façons : il s’exprime dans sa nature absolue (mode infinie immédiat), il s’exprime en tant que modifié (mode infini médiat), il s’exprime d’une manière certaine et déterminée (mode infinie existant). [ft.1 : E, I, 21-25] [Deleuze, 214b ; d]

It sometimes happens, that a man undergoes such changes, that I should hardly call him the same. As I have heard tell of a certain Spanish poet, who had been seized with sickness, and though he recovered therefrom yet remained so oblivious of his past life, that he would not believe the plays and tragedies he had written to be his own : indeed, he might have been taken for a grown-up child, if he had also forgotten his native tongue. If this instance seems incredible, what shall we say of infants? A man of ripe age deems their nature so unlike his own, that he can only be persuaded that he too has been an infant by the analogy of other men. (Elwes translation)From what Spinoza says about the decomposition of the body, it would seem that to change from child to man, or from poet to someone different, would be a decomposition, and thus a loss of power. But could it be that Deleuze takes the opposite view? To change from child to man is not an expression of our body's frailty. It rather shows our body's power to become something new. Imagine we get a sickness like the Spanish poet, and we no longer recognize our past selves. This would seem to be a loss of power. But that would only be so when we take the perspective of the self whom our body no longer expresses. But our bodies are always as perfect as they can be, given the conditions affecting them at any given moment. So to become someone else is not really a deprivation. It could be a testament to the power of our bodies to become new things, to express new essences. The question for Deleuze might not so much be "What can a body do?" as much as it might be "What can a body become?"

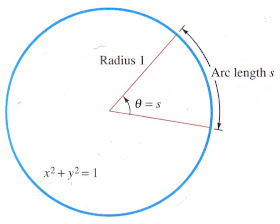

cos = cosignThere are six primary trigonometric functions:

sin = sine

tan = tangent

sec = secant

csc = cosecant

cot = cotangent

cos(–θ) = cosθ

and

sin(–θ) = –sinθ

Then, by working on the values, they give us the following formulas.cos2θ + sin2θ = 1

thus

thus also

1 + cot2θ = csc2θ

sin(α + β) = sin α cos β + cos α sin β

sin 2θ = 2sinθ cosθ

cos 2θ = cos2θ – sin2θ

= 2cos2θ – 1

= 1 – 2sin2θ

cos2θ = ½(1 + cos2θ)

sin2θ = ½(1 – cos2θ)