presentation of Edwards & Penney's work,

by Corry Shores

[Search Blog Here. Index-tags are found on the bottom of the left column.]

[Central Entry Directory]

[Mathematics, Calculus, Geometry, Entry Directory]

[Calculus Entry Directory]

[Edwards & Penney, Entry Directory]

Edwards & Penney's Calculus is an incredibly-impressive, comprehensive, and understandable book. I highly recommend it.

[I am not a mathematician; I am merely an admirer of Edwards & Penney's wonderful calculus book. Please consult the text or other references to be certain about anything in the summary below. I mean this emphatically.

The material here is from Edwards & Penney. Whenever it is not, I will indicate the source. Thanks:

Edwards & Penney

eugeneleeslover.com

mathworld.wolfram.coml

wikipedia

zonalandeducation.com

sparknotes.com

blog.ssis.edu.vn

elegantgirls.w-ru.com

mathforblondes.com

cliffsnotes.com

theroswellcode.com

mathimage.com

acoustics.salford.ac.uk

Math Demos

]

Review and philosophical application of

Edwards & Penney's Calculus

Trigonometric Functions

in

Section 1: Functions, Graphs, and Models

Subsection 4: Transcendental Functions

Edwards & Penney's Calculus

Trigonometric Functions

in

Section 1: Functions, Graphs, and Models

Subsection 4: Transcendental Functions

What Do Trigonometric Functions Got to Do with You?

Our lives course-by to many wave-like periodic patterns. Each day the sun rises-and-falls, increasing-and-decreasing light like a wave, with noon as the peak, and the middle of the night is the wave's bottom trough. And those of us living away from the equator experience another sort of waving of the light. Days get longer as we near summer solstice, and shorter as we head toward winter solstice. This can affect our moods, and as well the ways we feel about ourselves, the way we behave, the thoughts we have, and the way we relate and interact with others, loved-ones especially. On winter solstice, the darkness might feel heavy, like we are trapped under a blanket of black. Here we are at the bottom arc of the periodic curve. It might feel as if we are stuck forever in the winter darkness. Now consider more closely that exact moment of winter solstice when the earth enters its magic place along its revolution around the sun. We come upon the limit of the darkening trend. For a moment-out-of time, we no longer tend toward shorter days. And it is not yet until the next moment that the trend will change us toward longer days. Then as we near spring equinox, we can sense the tendency-toward-light increase. We can actually feel these tendencies immediately, as we witness the earth come alive again, erupting from its frozen slumber. And perhaps we too feel forces pushing our moods to the lighter and freer feelings of the summer.

There is something quite remarkable about these wave-like periodic patterns that we find in so many ways in our everyday experiences. They can be described by trigonometry and circles. At any moment in the cycle, a circle is being implicitly expressed. In a way, repetition is there from the beginning, and it is there at every instant. The wave patterns in the world and in our lives express circles in motion. There is an eternal recurrence in our lives, but it is not just the cycles repeating over-and-over seemingly without the intention of ending. Rather, recurrence is already there from the beginning, because the whole circle is implied at the start and it is implied in any instant. In a sense, the eternal form of the circle, and especially its internal structural relationships between its parts, is like a mythical eternal ground for our world and for our lives. It is eternal not because it happens infinitely, but because it is outside of time. All particular recurrences that we see in cyclical patterns happening through time were made possible on the grounds of an eternal recurrence that is outside of time and yet is implicitly immediate to every real moment of its expression in our lives.

Now, the circle just by itself is an expression of eternal repetition. The circle as it begins its motion implies already its return to its beginning. So consider the wave-like patterns which express a circle. The circle they express is eternal, because at any point along the waving change, the circle as a closed shape is already implied. In other words, the circle has returned upon itself even as its wave-expression begins. But this repetition is not possible on the basis of some sameness. The eternal is not a line that goes on forever. It is continually bending away from where it is, but back toward where it began. But when it returns back to where it began, it does not stop there. When it returns, the tendencies toward change are just as strong then as they were at every other place in the circle. And at every point along its changing course, the path is differing from itself already. The change is continuous because the motion always differs from itself. In other words, it is only because self-difference is always in the circle that there is the potential for it to return to itself. So we might think that the circle is everywhere the same. But we see that it is also everywhere tending away from itself, even while tending back toward itself in the same motion, like the snake biting its tail. In our own lives, we go from summer to summer. And it seems like each summer is similar to the rest. But what we experience is not a continual summer. What we experience is a continual self-differing as the changes proceed. We keep having summers only because they never stay the same. It would be one eternal summer if the circle's repetition were based on sameness. Rather, it is a matter of difference already there immediate to us that allows summer to tend away from itself, and welcome itself once again immediately upon itself. We only experience something again if we experience a different instance. We might find ourselves acting out a habitual action that makes us relate to ourselves in the past. But we can only encounter our past selves by meeting ourselves as other to ourselves. The identification is secondary, a matter of recognition. What is primary is that we are firstly different from ourselves.

So consider if we go from experience a to experience b; we can afterward say they are different. But we could not have arrived at b unless first difference paved the way. And we could not have begun at a unless a's way was already paved by difference. Difference is what is most immediate. The things that come to be called different are a secondary derived form of difference. But when we note that we go from summer to summer, from a to a, we should realize again that the second summer, the second a, first needed difference before it could arise. The same for the circle. We cannot say that it arrives back upon its beginning unless the beginning is already different from itself. A circle can begin and end at the same point, but only if that same point is different from itself, so it can serve on the one hand as the beginning, and on the other hand as the end. Now consider how the geometrical form of the circle implies this motion, but itself is not rotating. Any point along the circle is already a beginning and end, a self-different point, a point that treats of itself as being different from itself. Now, what the cycles of our life and world imply is a geometrical circle. Such circles might express themselves in durational wave-like patterns, but as a formal element to that pattern, the circles are outside duration; they are eternal. The circle then should hardly evoke in us the idea of eternal sameness. It is eternal difference, an always and everywhere self-difference.

So as we notice cycles in our lives, we could on the one hand think about how things are somehow both same and different, how there are always ambiguities. We can in addition consider that when we for example lie down to sleep, we are not just sleeping again, or having a different sleep, but that we are immediately experiencing an eternal repetition of difference. Sure, each sleep is unique. But it expresses a difference more profound than its uniqueness. Each sleep is an expression of the difference which made it possible. The eternal substance of all our experience, of everything in our world, is difference.

So if there is one thing that is always repeated eternally, it is difference. The eternal circles implied in the many waves in the world and in our lives are testiments to a more profound eternity, the eternal difference, the eternal return of difference.

Brief Summary

The relations between the sides and angles of a right triangle can be described through the science of trigonometry. We may then apply these relations to angles in circular variation. By doing so, we are able to describe the wave-like periodic patterns in the natural world. Points Relative to Deleuze

[Under Ongoing Revision]

For Deleuze, our sensations are matters of continuously varying waves. Affection in general is a matter of such a continuous variation. We wonder, why a wave? Is there not continuity to a wave, and thus not complete difference and heterogeneity? Or is there something heterogeneous and discontinuous in the series of tendency-changes along a wave? We should try to be specific about why Deleuze speaks of these waves of sensation, especially considering that sensation is a matter of difference and a discontinuity in our experiences. I currently suspect that the wave is a useful image, because on the one hand there is a continuity in the series; each point or limit is immediately near its neighbor. However, on the other hand there is a discontinuity in the series of tendencies (differentials), moving from one limit to the next along the wave's curves. [Under Ongoing Revision]

Edwards & Penney

Appendix C: Review of Trigonometry

Appendix C: Review of Trigonometry

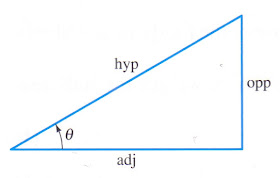

We begin looking at a right triangle.

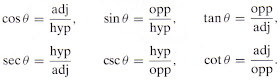

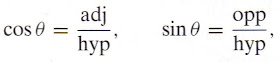

We see the right angle in the bottom right corner. The other two must then total 90 degrees, so they both must be acute (less then 90 degrees). The trigonometric functions will be ratios between sides of angles, relative to the acute angle in question. We may arbitrarily pick which of the two acute angles to be θ (theta). Then, the side opposite to theta will be considered the "opposite" side. There are two lines that will come out of theta. One will be opposite to the right angle. This is always the "hypotenuse". The other line extending alongside theta is called the "adjacent" side. We now make ratios of the lengths of the sides. For example, we might take the ratio of the opposite angle over the hypotenuse. By doing so, we have defined the "sine" of theta. When we instead take the ratio of the adjacent line over the hypotenuse, we have then determined the "cosine" of theta. We will use the following abbreviations:

cos = cosignThere are six primary trigonometric functions:

sin = sine

tan = tangent

sec = secant

csc = cosecant

cot = cotangent

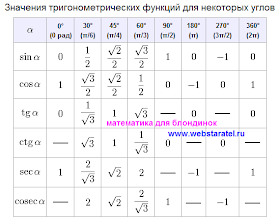

Here by the way is a table calculating the values for our approximations [click to enlarge]

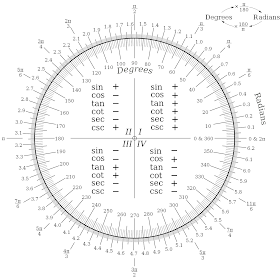

We might also consider these angles more dynamically. They could be formed by a rotation of sorts.

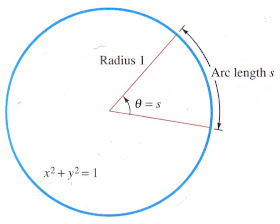

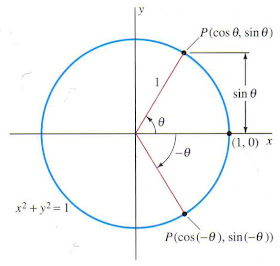

An angle created by rotation is called a directed angle. Using the image above, we imagine that first the two lines extending from the angle both begin together along the right side of the x axis. Then, one of the lines rotates away while the other remains on the x axis. If the rotation of the line moves counterclockwise, we consider the angle to be a positive angle. But if it goes clockwise, we instead consider it to be a negative angle. We consider P(x,y) to be the point where the moving (terminal) side of theta intersects with the circle. This circle we define as

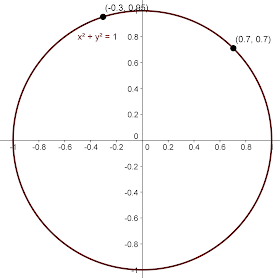

Let's break from Edwards & Penney to give more background on the circle. Its formula is:

The center-point is (a, b), and r is the radius. To make things easier, we will just make the center-point (0, 0). This way we simplify the formula to.

To form a 'unit circle', we make the radius one unit, that is, equal to 1.

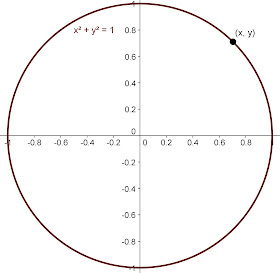

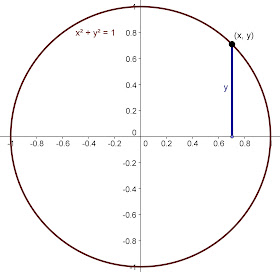

Now let's pick some point (x, y) on the circle.

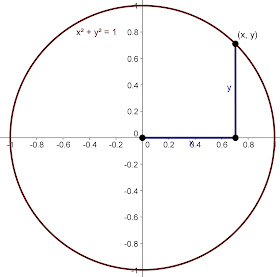

We could then drop a line down from this point to the x-axis.

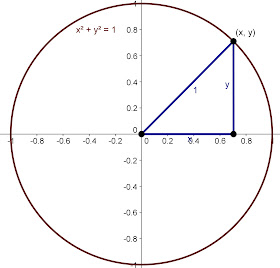

It will have the value y, because it extends directly up the y axis. Then we can get the x value by extending the line from that new corner to the origin.

Then finally the radius line going out to our point on the circle will be 1, because we have defined the radius that way.

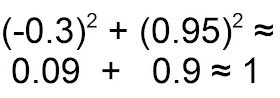

Using the Pythagorean theorem, we see that we return again to our circle formula:

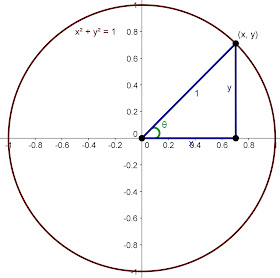

So let's consider angle theta.

And recall the formulations for cosine and sine.

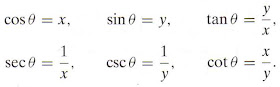

We see that they are both set over the hypotenuse. But the hypotenuse is 1. The adjacent angle is x. And the opposite angle is y. Hence we can define the following [and we return now to Edwards & Penney]:

We make some assumptions in the above. For tan θ and sec θ, we assume that x ≠ 0 [so that we do not have a number divided by zero]. And for cot θ and csc θ, we assume that y ≠ 0.

If we make substitutions in the above equations, we can use sine and cosine to define the others.

Edwards & Penney then have us compare the angles θ and -θ in this figure:

Notice that the x and y lines will be the same length. Hence:

cos(–θ) = cosθ

and

sin(–θ) = –sinθ

Then, by working on the values, they give us the following formulas.The Fundamental Identity of Trigonometry:

cos2θ + sin2θ = 1

thus

1+ tan2θ = sec2θ

thus also

1 + cot2θ = csc2θ

The Addition Formulas:

sin(α + β) = sin α cos β + cos α sin β

cos(α + β) = cos α cos β – sin α sin

The Double-Angle Formulas:

sin 2θ = 2sinθ cosθ

cos 2θ = cos2θ – sin2θ

= 2cos2θ – 1

= 1 – 2sin2θ

The Half-Angle Formulas

(These, they say, are particularly important in integral calculus):

cos2θ = ½(1 + cos2θ)

sin2θ = ½(1 – cos2θ)

Radian Measure

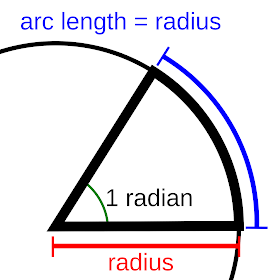

Normally we measure measure angles in degrees, like 360°, 90°, etc. However, there is another means called radian measure. It is often more convenient, and even at times essential, to use radian measure in calculus. So consider this image below [first one from wikipedia]

[Thanks wikipedia.org]

Here we see that the radius has a certain length, and it equals the circle's arc created by the angle. We say that the angle 'subtends' in the arc. And the length of the arc equals the length of the radius. This wonderful animation from zonalandeducation.com shows how the lengths are equal.

Now consider this animation. It shows that when the diameter of circle is 1 unit, the circumference is pi (π) units.

So the diameter multiplied times π will tell us the circumference. This means also that the formula for the circumference could be rendered, when in terms of the radius:

C = 2πr

So the radius measure, times 2π, will give us the circumference. But we are also dividing that circumference up into radius length arcs. Each one corresponds to a fixed angle measure, which we can convert into degrees if we wish. So we know that the circumference is 2π times the radius measure. That corresponds to the total of all the internal angle-measure, which is 360°. If 2π times the radius gives us 360°, then π times radius gives us 180°. On this basis, we can calculate conversions between radians and degrees.

Here are some conversion charts [The second one is from Edwards & Penney]:

Recall also the formula for the area of a circle:

From this we can obtain the following formulas

Section 1: Functions, Graphs, and Models

Subsection 4: Transcendental Functions

Trigonometric Functions

Subsection 4: Transcendental Functions

Trigonometric Functions

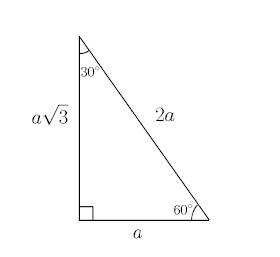

Now first consider this 30-60-90 degree triangle.

We see that the sine for the 30 degree angle will be a/2a, or 1/2. And using our conversion methods, we see that this is equal to π/6 radians.

So we see for example these equivalences charted on tables such as these:

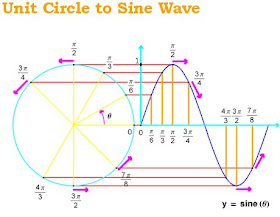

Now consider this diagram:

Here it is in radian measures:

See how the 30 degrees (π/6) on the sine of the circle corresponds to the 0.5, or half-way up the sine wave to the right? A great animation for how the sine wave is formed from the circle values can be seen here.

I tried to capture it, but the quality is much better at the source. [Also it is a wonderful source for many other acoustic related things ideas].

Here is another great animation from Math Demos [Also much better seen at its source]:

And this one is from wikipedia.

And here is one for cosine:

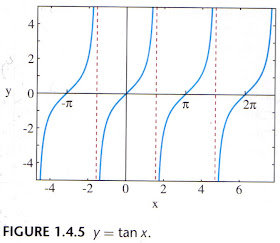

For tangent,

And for cosecant:

Now consider this diagram:

Here it is in radian measures:

See how the 30 degrees (π/6) on the sine of the circle corresponds to the 0.5, or half-way up the sine wave to the right? A great animation for how the sine wave is formed from the circle values can be seen here.

I tried to capture it, but the quality is much better at the source. [Also it is a wonderful source for many other acoustic related things ideas].

Here is another great animation from Math Demos [Also much better seen at its source]:

And this one is from wikipedia.

And here is one for cosine:

For tangent,

And for cosecant:

Now let's also consider when we let the sine wave continue. It repeats its regular oscillation

.

This is called the periodicity of the trigonometric functions. Every 2π the unit circle rotation returns to where it began. So too does the sine wave pattern repeat its period with each return. Hence

sin(x + 2π) = sin x and cos(x + 2π) = cos x

When we shift ('translate') the cosine graph by π/2, we get the sine graph.

Example 2:

Consider this graph.

It charts the average daily temperatures in Athens, Georgia, USA. It begins in the middle of July, and returns to the next middle of July. As we would expect, the temperatures are higher in the summer, and lower in the winter. They swing like a wave. In this case, the pattern resembles a cosine wave. The formulation that describes this wave is [where average temperature is T in °F, and the number of months after July 15 are t]:

So let's consider October 15, which is three months after July 14. We will then substitute 3 for t. What we obtain is 61.3°F. Note first that the substitution gives us cos(3π/6 ). This is the same as π/2. Recall from the chart that this cos (π/2) = 0.

So now working out the equation is easier:

And of course, this pattern is periodic, which means that in 12 months it returns to where it began.

See especially the enlargement of the mathdemos one above:

The tangent is the blue segment's length divided by the green segment's length. When we near the π/2 part, we have a number divided by an increasingly small number. So 1/ 0.000001 is 1,000,000. As the smaller number nears zero, the quotient of the two nears infinity, hence the tangent lines flying-off to infinite heights. This also means, however, that unlike the sine and cosine graphs, the tangent graph has 'infinite' gaps. Where the top part leaves-off is infinitely high, and where the bottom part picks-up immediately after is infinitely low. Such gaps are called discontinuities. We will later discuss them in more depth.

from Edwards & Penney: Calculus. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2002, pp. A13-15; 33-36.

Image Credits:

Nearly all from Edwards & Penney, except,

Table of Natural Trigonometric Functions:

http://www.eugeneleeslover.com/USNAVY/TRIG-FUNCTIONS.html

Triangle in the circle:

http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Trigonometry.html

Large radian:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Radian_cropped_color.svg

Radian animation:

http://zonalandeducation.com/mmts/trigonometryRealms/radianDemo1/RadianDemo1.html

Diameter wheel:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pi-unrolled-720.gif

Radian table:

http://www.sparknotes.com/math/trigonometry/angles/section2.rhtml

1st radian conversion circle:

http://blog.ssis.edu.vn/chrischoi/2010/04/08/precal-unit-circle/

2nd radian conversion circle:

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Degree-Radian_Conversion.svg

30-60-90 degree triangle:

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:30-60-90_triangle.jpg

Radian trigonometry conversion chart 1:

http://elegantgirls.w-ru.com/inf_trig.html

Radian trigonometry conversion chart 2:

http://www.mathforblondes.com/2010/07/trigonometric-table.html

Radian trigonometry conversion chart 3:

http://www.cliffsnotes.com/study_guide/Trigonometric-Functions.topicArticleId-39909,articleId-39868.html

Sine and Cosine with Circle:

http://www.theroswellcode.com/ArticleDNA.html

Unit circle to sine wave:

http://www.mathimage.com/see_mi_UnitCircleToSineWave.jsp

3D sine wave animation:

http://www.acoustics.salford.ac.uk/feschools/waves/shm2.htm#sine

Math Demos animations all from:

http://mathdemos.gcsu.edu/mathdemos/family_of_functions/trig_gallery.html

Wiki animations from:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trigonometry

No comments:

Post a Comment