by Corry Shores

[Search Blog Here. Index-tags are found on the bottom of the left column.]

[Central Entry Directory]

[Deleuze on Bacon Entry Directory]

Variations on a Line:

Wilhelm Worringer's Northern Line (Gothic Line)

Wilhelm Worringer's Northern Line (Gothic Line)

What does Gothic got to do with you?

By looking within ourselves, we might discover a force of freedom thriving within us. It is not exactly that part of us which is like self-defiance, an element in our personalities that causes us to act in a self-sabotaging way against our best interests, or to recklessly act without thinking. However, it is very similar, and might best be described by considering first certain elements of this more readily conceivable careless freedom. For, unlike the reckless freedom, the other more freer freedom is not a reaction. It does not react against ourselves or against things, people and events in our lives. So consider for example that force in us that might drive us to spontaneously go on a drinking binge after just losing a job. It cannot be this other freer freedom, because it reacts against an unfavorable event, an unfair boss, or a self-pitying and self-despising self. Yet it is a sort of defiance. And maybe the freer freedom is defiance without there first being something that we are defying against. Of course we are born into power structures, but our actions can have the spirit of pure, non-reactive defiance. Perhaps this is what we see in the moments of great artistic creation, a sort of joyful defiance, a continual denying that there ever was a restriction in the first place. Now imagine we try to express this force in the act of drawing a line. But also consider if we first drew a curve with supreme control over our hand, to make it as perfect as possible. And also imagine that we at another time were violently impulsive, and drew an erratic line. But the third case is a line inspired by the freer freedom. Like the nicely-drawn curve, the free line would not be a messy chaos. But also, the free line will not be as regularized. And like the erratic impulsive line, the free line will be liberated from the expectations set by how the line was being previously rendered. In a sense it lives at the tiny infinitely small point of the absolute present moment, never fully bound to the immediate or passing past. But unlike the erratic line, the free line will not be defiant in an artificial or reactive way.

So in one sense the free line is drawn in the infinitely small present moment. But in every such infinitely small moment, the line is tending toward extending into infinity. That is because at no moment does it suggest or move toward an organic completion. How is this so? Consider lines that make a labyrinthine pattern.

Such labyrinthine patterns make us think that there is no beginning or end. Another example is a Gothic cathedral.

Only the vertical lines are emphasized, which gives us an impression of going up to infinity.

Worringer calls the free line the "Northern line." If we drew our lives as a northern line, we would not be bound to our pasts, or adjust our actions so that they properly react to something else. We would live in the present not in a thoughtless or careless way, but in the sense of making this moment the seed of an infinite future of continued freedom. Such a 'northern life' is powerfully creative.

Brief Summary:

Worringer discusses certain styles that cultures have developed throughout history. There is a trend, called the Gothic, which ornaments its works with a liberated line, termed the "Northern Line". This line is continually undetermined and it strives for infinity.Points relative to Deleuze

[Under continual revision]:

[Under continual revision]:

One of the places Deleuze refers to the northern line is in his Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation book. One element that is central to his notion of sensation is continual variation. So consider a part of a painting that we might characterize as being northern or Gothic; it would have lines that are in continuous variation. Visually speaking, this line will act on the other elements of the painting. But because it is in continual variation, then it expresses either explicitly or implicitly self-difference at every point. Thus there is an infinity of different influences it has on the rest of the painting. This prevents our eyes from ever satisfying their effort to make visual sense of what they see. There will never be an organic coherence, because the artwork will be infinitely fertile in the ways its parts can re-relate. This continual defiance to our efforts of recognizing or mentally representing what we see causes our impressions to be in continual variation. We have a sensation when we are confronted with an irreducible difference that forces itself upon us. Thus the northern or Gothic line can be an element of a painting which allows the artwork to continually affect us with its constant variation.

Selective Summary, from:

Wilhelm Worringer

Form Problems of the Gothic

Wilhelm Worringer

Form Problems of the Gothic

Latent Gothic of Early Northern Ornament

Worringer will speak of "three principal stages in the process of adjustment of man to outer world" (43). He will focus on the Gothic stage, which he says does not correspond with the Gothic historical age. Rather, he examines the Gothic in terms of a "psychology of style" (43b). All the Western World is Gothic in this sense, so long as it is not immediately influenced by the antique Mediterranean culture. Thus Gothic refers to present times as well (44a).

Worringer begins by describing the art of the Northern European peoples at the fall of the Roman Empire. (45d) The art does not represent nature. It is purely ornamental. There is a "purely geometrical play of line" (although he will later clarify this sort of playfulness). (46ab)

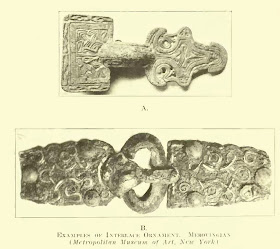

They begin to develop their own language of the line, their own "linear fantasy called intertwining band ornament or braid ornament" (46bc).

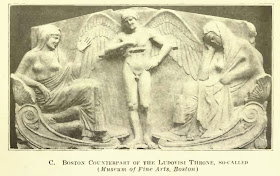

The lines form various fantastic and intriguing arrangements. Early primitive lines are abstract and geometrical, without any organic interpretation. (47a) Nevertheless, they express an extreme liveliness. (47b) He says that this line style we see above is a clash between "the abstract character of primitive geometric ornament" and "the living character of Classical organically tinged ornament" (47b.d) These two other styles shown respectively.

So, classical ornament has organic clearness and moderation, and it seems to spring "without restraint from our sense of vitality." And also, "It has no expression beyond that which we give it" (48b). But by contrast, northern ornament seems to take on a life all its own, and in fact seems to act upon us ourselves.

The expression of northern ornament, on the other hand, is not immediately dependent upon us; here we face, rather, a life that seems to be independent of us, that makes exactions upon us and forces upon us an activity that we submit to only against our will. In short, the northern line is not alive because of an impression that we voluntarily impute to it, but it seems to have an inherent expression which is stronger than our life. (48bc, boldface mine)The elaborate his idea of the northern line, he illustrates with common experience. We are to pick up a pencil and draw a line.

What do we notice? Worringer suggests we sense two things. One is "the expression dependent upon us" and the other is the "expression of the line seemingly not dependent upon us" (48d). Perhaps in one way, we see that we drew it; we see that it is a line from our hand not that that of someone else. But perhaps in another way, we see a geometrical form that we were trying to render. The line, as a line, expresses something that is geometrically real even without such an attempted instantiation.

He also has us draw the line in "fine round curves". When we do so, we feel the movement of our wrist. But to that motion we also accompany to it our "inner feeling". We sense that the line grows spontaneously from the play of our wrist, and this gives us a pleasant sensation. "The movement we make is of an unobstructed facility; the impulse once given, movement goes on without effort." (48d). This pleasant feeling is a "freedom of creation," and we transfer it

involuntarily to the line itself, and what we have felt in executing it we ascribe to it as expression. In this case, then, we see in the line the expression of organic beauty just because the execution corresponded with our organic sense. (48-49)But consider if we see a line made by someone else. We will still involuntarily feel inside us the impressions one has if drawing such a line. (49a)

Gothic lines may have this "organic expressive power", like we see in Classical ornament. But it has another such expressive power. Worringer has us imagine drawing a line more excitedly.

If we are filled with a strong inward excitement that we may express only on paper, the line scrawls will take an entirely different turn. The will of our wrist will not be consulted at all, but the pencil will travel wildly and impetuously over the paper, and instead of the beautiful, round, organically tempered curves, there will result a stiff, angular, repeatedly interrupted, jagged line of strongest expressive force. It is not the wrist that spontaneously creates the line; but it is our impetuous desire for expression which imperiously prescribes the wrist's movement. The impulse once given, the movement is not allowed to run its course along its natural direction, but it is again and again over whelmed by new impulses. When we become conscious of such an excited line, we inwardly follow out involuntarily the process of its execution, too. (49b.d, boldface mine)But when we follow someone else's wild line, we do not feel pleasure. It seems more like "an outside dominant will coerced us" (49cd). What we feel seems like the forces of the ruptures in the line's incoherent discontinuity.

We are made aware of all the suppressions of natural movement. We feel at every point of rupture, at every change in direction, how the forces, suddenly checked in their natural course, are blocked, how after this moment of blockade they go over into a new direction of movement with a momentum augmented by the obstruction. The more frequent the breaks and the more obstructions thrown in, the more powerful becomes the seething at the individual interruptions, the more forceful becomes each time the surging in the new direction, the more mighty and irresistible becomes, in other words, the expression of the line. (49-50, boldface mine)The line forces its expression upon us. Thus we feel it as something autonomous and independent of us. (50a)

So consider when we were drawing the curved line. We felt physically a pleasure on account of there being no obstructions breaking the flow of our hand's movements. The parts of our wrist worked together to create a line that is self-consistent in its curving motion. With the erratic line, however, there seems to be unpredictable forces which break the flow, in fact prevent one from starting, and prevent any possibility of there being coherence in the motions or the line. Our hands drawing calmly seem to do so merely by means of our bodies acting automatically and with coordination among its parts. So when it is erratic, that suggests to us the forces causing the unpredictabilities do not come from the body, but rather from some psychic or spiritual source.

The essence of this inherent expression of the line is that it does not stand for sensuous and organic values, but for values of an unsensuous, that is, spiritual sort. No activity of organic will is expressed by it, but activity of psychical and spiritual will, which is still far from all union and agreement with the complexes of organic feeling. (50b, boldface mine)Worringer clarifies that Gothic ornament and such a scrambled line made by an emotionally or mentally excited person are not at all the same things. However, Worringer will compare them to clarify what he means by the northern line. He says for example that the lines of northern cultures tell us that they were

longing to be absorbed in an unnatural intensified activity of a non-sensuous, spiritual sort one should remember in this connection the labyrinthic scholastic thinking in order to get free, in this exaltation, from the pressing sense of the constraint of actuality. (50d, boldface mine)Worringer sees this supersensuous longing expressed in "fervent sublimity of the Gothic cathedral, that transcendentalism in stone" (51a). Such architecture exhibits "a complete degeometrization of the line for the sake of the same exigencies of spiritual expression" (51ab).

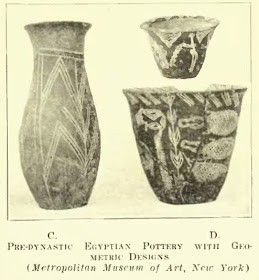

Pointing us to the left item in the image below, Worringer tells us that "primitive ornament is geometric, is dead and expressionless [Pl. III, C]. Its artistic significance rests simply and solely upon this absence of all life, rests simply and solely upon its thoroughly abstract character" (51b).

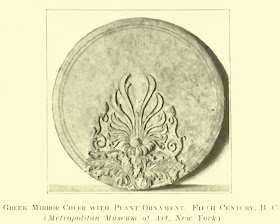

Worringer then says that the original dualism between man and world weakened the geometrical character of the line. This degrading of the geometrical line can take two courses. One is toward "an organic vitality agreeable to the senses," as with classical ornament. (51bc)

Or instead it can develop toward a "spiritual vitality, far transcending the senses," which we see in northern ornament (51c). Here we find the Gothic character.

He continues to claim that the Gothic has more expressive power.

And it is evident that the organically determined line contains beauty of expression, while power of expression is reserved for the Gothic line. This distinction between beauty of expression and power of expression is immediately applicable to the whole character of the two stylistic phenomena of Classic and Gothic art. (51cd, boldface mine)

The Infinite Melody of Northern Line

Worringer will further elaborate the distinction between Classical ornament and Gothic/northern ornament.

Classical ornament exhibits symmetry.

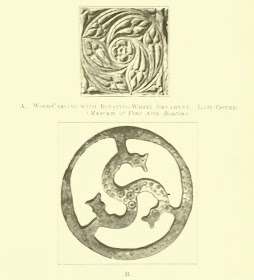

However Gothic does not. But instead of symmetry repetition is predominant. (52ab) Classical has repetition too, but like a mirroring. The repetitions have the "calm character of addition that never mars the symmetry" (52bc).

Gothic repetition, however, is more like a repetition of difference striving to rise to the nth power.

In the case of northern ornament, on the other hand, the repetition does not have this quiet character of addition, but has, so to speak, the character of multiplication. No desire for organic moderation and rest intervenes here. A constantly increasing activity without pauses and accents arises, and the repetition has only the one intention of raising the given motive to the power of infinity. The infinite melody of line hovers before the vision of northern man in his ornament, that infinite line which does not delight but stupefies and compels us to yield to it without resistance. If we close our eyes after looking at northern ornament, there remains only the echoing impression of incorporeal endless activity. (52-53, boldface mine)

Worringer then cites work from Lamprecht where he describes the laberinthine nature of the Gothic lines.

Lamprecht speaks of the enigma of this northern intertwining band ornament, which one likes to puzzle over [PI. VIII]. But it is more than enigmatic; it is labyrinthic. It seems to have no beginning and no end, and especially no center; all those possibilities of orientation for organically adjusted feeling are lacking. We find no point where we can start in, no point where we can pause. Within this infinite activity every point is equivalent and all together are insignificant compared with the agitation reproduced by them. (53a.b, boldface mine)In Gothic architecture, "the impression of endless movement results from the exclusive accentuation of the vertical." (53c)

From:

Wilhelm Worringer. Form Problems of the Gothic. New York: G.E. Stechert, 1920.

PDF available online at:

http://www.archive.org/details/formproblemsofth00worruoft

No comments:

Post a Comment