by Corry Shores

[Search Blog Here. Index tabs are found at the bottom of the left column.]

[Central Entry Directory]

[Jakob von Uexküll, entry directory]

[Jakob von Uexküll, Theory of Meaning, entry directory]

[The following is summary. Bracketed commentary and boldface are my own, unless otherwise noted. Citations refer first to the German 1940 edition, secondly to the 1982 English edition, and thirdly to the 2010 English edition. When quoting, the source version will be indicated in citation by having its page numbers underlined. I apologize in advance for typos, as proofreading is incomplete. Note: quotations from the 1982 edition may contain asterisks, which “appear before words contained in the Glossary the first time they occur in the text” (79). I will give that glossary definition when the appear. Also, German terms are repeatedly inserted to facilitate comparison with translations of other Uexküll texts]

Summary of

Jakob von Uexküll

Theory of Meaning

[Bedeutungslehre]

2. The Meaning-Carrier

[Carriers of Meaning]

[Bedeutungsträger]

Brief summary:

From the perspective of a biologist, there are no neutral objects. Each thing has a meaning depending on which Umwelt (subjective world of an animal) it is in and what role it plays in that animal’s life. The stem of a flower, for example, serves a different role in the lives of a girl, an ant, a cicada, and a cow. For the girl, the stem is a way for her to fix the flower in her clothes as decoration. For the ant, the stem is a path to its food source, the petals. For the cicada, the stem is the storage place for sap that it will extract and use as a housing substance. And for the cow, the stem is simply food. Objects as things with such functional significance in an animal’s Umwelt and life are thus meaning-carriers (Bedeutungsträger). Objects have many properties. But depending on the role they play, certain properties will have certain statuses. One set of such statuses involves the role they play in the object’s functionality for the animal. What makes an object a useful object is the structural ways that the parts or properties lend to the functioning of the whole. We consider a transparent glass bowl and two of its properties, namely, its roundness and its transparency. When it is used as a window pane, its main function is to allow light through it, and thus its key or leading property [leitende Eigenschaft] is its concavity. But its secondary function is to obscure what is going on inside the house, and thus its subsidiary or supporting property [begleitende Eigenschaft] is its concavity. However, suppose we set it on the table and fill it with a liquid. In this case, its leading property is its concavity, as this allows it to hold the fluid, while its subsidiary property is its transparency, as this serves the secondary function of allowing us to view its contents better. Another way to classify the properties of an object has to do with the functional circles [Funktionskreise], which are similar to stimulus-response reflexes, except they involve meaning creation and transformation. Certain properties take on a significance for the animal in that they inform the animal about an action they may want to take. These properties that the animal is receptive to sensorily are perceptual cue-carriers [Merkmalträger]. They trigger the animal to make an effective action in the world, often times acting upon the very same thing that trigger the action. The object will have certain properties or parts that the animal interact with specifically, and by doing so, the animal either physically transforms the properties of the object or at least transforms its significance. The properties involved in the animals effective action, but which are not necessarily perceived by the animal, are the effector cue-carriers [Wirkmalträger], because they serve to facilitate the effective action and/or they possess marks of the result of that effective action. Since the effective action may either transform the object physically, thereby altering the properties that were once perceived, or it will at least transform its meaning so that the properties that were once perceived are no longer relevant after the action is completed. Either way, the effector cue-carriers extinguish the perceptual cue-carriers. The cow, for example, senses things about the flower and its stem (its taste primarily) which tell it to eat the flower. But after eating it, those properties are not longer sensible, and the chewed flower carries the effector cues. So physically the perceptual cue-carriers were extinguished. But also, the flower went from some thing in the field to food. This transformation of meaning makes the perceptual cue-carriers no longer relevant, because its new meaning has designated it as food, and thus there need no longer need to continue perceiving its properties, which only serve to make that designation anyway. So in that sense the effector cue-carrier extinguishes the perceptual cue-carrier. And finally, after the cow eats, it is full, and thus no longer is interested in perceptual cue-carriers indicating food. Thus in this way again the perceptual cue-carrier has been extinguished by effector cue-carrier. Yet the perceptual cue-carriers and the effector cue-carriers do not exhaust all the properties of the object. There are still others which serve in forming the objective connecting structure [Gegengefüge]. This notion remains vague, but it is defined as the physical component of the object which connects the perceptual cue-carriers to the effector cue-carriers. We might then think of the object as a unity of properties. There is something structural about it responsible for how those properties hang together (which could be simply physical connections of material parts or it could be things which lend themselves to different sorts of sensible properties, like vibration being something both visible and audible).

Summary

§16

[When we see winged insects, we think they have complete freedom to go anywhere in the world.]

When we see winged insects flying around a field, we think that their world is boundless, because they seemingly move about from place to place at will (3/26/139).

§17

[Even many earthbound animals seem to have this freedom of movement.]

This freedom seems to hold for many earthbound animals as well, like frogs, mice, snails, and worms (3/27/139).

§18

[But in fact, all animals are limited to a particular dwelling-world (habitat / Wohnwelt), and ecologists should study these limits.]

But in fact, all animals are limited to their habitat.

This impression is deceptive. In truth, every free-moving animal is bound to a specific habitat [dwelling world / Wohnwelt] and it remains the task of the ecologist to investigate its limits.

(3/27/139, bracketed insertions mine)

§19

[There is a comprehensive world out of which the animal carves its habitat (Wohnwelt). Within its habitat is a limited range of objects (Gegenstände), with which the animal has a limited range of interactions, which biologists can study.]

[So each creature has its own habitat. And within its habitat are certain limited range of objects. And the creature’s range of interactions with those set objects might itself be more or less limited. This can seem to present to biologists the task of finding the certain uniform ways that creatures interact with the limited range of objects in their habitat.]

We do not doubt that a comprehensive world [enclosing world / umfassende Welt] is at hand, spread out before our eyes, from which each animal can carve out its specific habitat [dwelling world / Wohnwelt]. Observation teaches us that each animal moves within its habitat [dwelling world / Wohnwelt] and confronts a number of objects [Gegenständen], with which it has a narrower or wider relationship. Because of this state of affairs, each experimental biologist seems to have the task of confronting various animals with the same object [Gegenstand], in order to investigate the relationships between the animal and the object [Gegenstand]. In this procedure, the same object represents a uniform standard measure in every experiment.

(3/27/139, bracketed insertions mine)

§20

[Experiments have been done on rats’ relations to a labyrinth.]

Uexküll notes that this sort of analysis has been carried out by American researchers with respect to animals in their relationship to a labyrinth (3/27/139).

§21

[The problem with these experiments is that they wrongly assume that animals can enter into a relationship with a neutral object (Gegenstand).]

Uexküll says that these experiments fail, because they are “based on the false assumption that an animal can at any time enter into a relationship with a *neutral object [(just ‘object’) / (just ‘Gegenstand’)] ” (3/27/139, bracketed insertions mine).

[From the Glossary:

Neutral object (Gegenstand) An object in the *Umwelt of an indifferent observer. It is never contained in the Umwelt of an animal. ‘Because no animal ever plays the role of an observer, one may assert that they never enter into relationships with neutral objects.’ (J. v. Uexküll; above, p. 27).”

(85)

Reference:

(This text)

]

§22

[Consider if we scare off a dog by picking up a stone from the road and throwing it at the dog.]

To explain why these attempts fail, Uexküll uses the following illustration. Suppose we are walking down a country road, and an angry dog barks at us. To scare off the dog, we pick up a stone from the road and throw it toward the dog to frighten it off. At this point, we can note that it was one and the same stone that previously was on the road and secondly was thrown at the dog (3/27/140).

§23

[The physical composition of the stone did not change; only its meaning changed.]

Nothing about the stone’s physical properties or chemical composition has changed at all, however, its meaning has changed with the new role it plays in this situation.

Neither the shape, nor the weight, nor the other physical and chemical properties of the stone have altered. Its color, its hardness, and its crystal formation have remained the same and yet, a fundamental transformation has taken place: It has changed its meaning [Bedeutung].

(3-4/27/140, bracketed insertions mine)

§24

[While the stone was on the road, it functioned to support the walker’s feet, and thus at that time had a path-quality (path tone / Wegton).]

While being on the road, it had a “path-quality” [“path tone” / “Wegton”], because it was “incorporated in the country road” and it “served as a support for the walker’s feet” (4/27/140, bracketed insertions mine).

§25

[But when it is thrown, a new meaning is imprinted upon it, namely, a throw-quality (throwing-tone / Wurfton), because its function changed and thus its meaning changed.]

But when being thrown, it obtained a “throw-quality” [“throwing tone” / “Wurfton”], because it now functions as a missile. So it loses its old quality, and this new one is “imprinted upon it”, when its function alters (4/27/140, bracketed insertions mine).

[The following collects the above paragraphs in quotation.]

The proof of this seemingly surprising assertion is easy to demonstrate by means of a simple example: Let us suppose that an angry dog barks at me on a country road. In order to drive it off, I pick up a stone and frighten it off with an adept throw. Nobody who observes this process and afterwards picks up the stone would doubt that it was the same object, ‘stone’, which first lay on the road and then was thrown at the dog.

Neither the shape, nor the weight, nor the other physical and chemical properties of the stone have altered. Its color, its hardness, and its crystal formation have remained the same and yet, a fundamental transformation has taken place: It has changed its meaning.

As long as the stone was incorporated in the country road, it served as a support for the walker’s feet. Its meaning in that context lay in its playing a part in the performance of the path, we might say that it had acquired a ‘path-quality’ (Weg-Ton).

This changed fundamentally when I picked up the stone to throw it at the dog. The stone became a missile – a new meaning became imprinted upon it. It had acquired a ‘throw-quality’ (Wurf-Ton).

(3-4/27/140)

[from the other translation:]

The proof of this surprising-sounding assertion can be provided by a simple example. The following case is treated as given: An angry dog barks at me on a country road. In order to get rid of him, I grab a paving stone and chase the attacker away with a skillful throw. In this case, nobody who observed what happened and picked up the stone afterward would doubt that this was the same object, “stone,” which initially lay in the street and was then thrown at the dog.

Neither the shape, nor the weight, nor the other physical and chemical properties of the stone have changed. Its color, its hardness, its crystal formations have all stayed the same — and yet it has undergone a fundamental transformation: it has changed its meaning. As long as the stone was integrated into the country road, it served as a support for the hiker's foot. Its meaning was in its participation in the function of the path. It had, we could say, a “path tone.” That changed fundamentally when I picked up the stone in order to throw it at the dog. The stone became a thrown projectile — a new meaning was impressed upon it. It received a “throwing tone.”

(3-4/27/140)

§26

[When one is an objective observer of neutral objects, they have no meaning, because meaning is imprinted on objects when they enter into a relationship with a subject. Animals never relate to neutral objects, because they are never mere observers.]

Uexküll then has us think of an observer holding the stone in her hand, with the stone being a relationless object. But the stone becomes a carrier of meaning when it enters a relationship with a subject. [The idea seems to be that insofar as the object is not related to something else but is merely something noted by an uninvolved observer, it is not carrying meaning. But as soon as it involves other subjects to which it plays some role in their lives or experiences, then it becomes a meaning-carrier.] Uexküll then says that animals never play the role of observers, and thus every object carries meaning for them. [I am not certain however why animals cannot be disinterested observers.] This meaning is endowed to the thing by some subject.

The stone lies in the objective observer’s hand as a neutral object [relationless object / beziehungsloser Gegenstand], but it is transformed into a *meaning-carrier [carrier of meaning / Bedeutungsträger] as soon as it enters into a relationship with a subject. Because no animal ever plays the role of an observer, one may assert that they never enter into relationships with neutral objects [“object” / “Gegenstand”]. Through every relationship the neutral object [object / Gegenstand] is transformed into a | meaning-carrier [into the carrier of a meaning / in den Träger einer Bedeutung], the meaning of which is imprinted upon it by a *subject.

(4/27-28/140, bracketed insertions mine)

[From the Glossary:

Meaning-carrier (Bedeutungsträger) The properties of a *neutral object that | acquire a meaning in the *Umwelt of a *subject. Every neutral object ‘is transformed into a meaning-carrier as soon as it enters into a relationship with a subject ... The meaning ... is imprinted upon it by a subject.’ ‘... the meaning-carriers ... in various Umwelts ... remain identical in their structures. Part of their properties serve the subject at all times as perceptual cue-carriers, another part as effector cue-carriers’. (J. v. Uexküll; above, pp. 27-28, 31)

(84-85)

Reference:

(This text)

Subject (Subjekt) The point of reference for any *meaning, since the value of a subject does not reside in something else, ‘but rather lies in its own existence, in its own self’. It is also the center of an *Umwelt, which is built up by the subject as a receiver of *signs that are interpreted according to a species-specific code. In its reactions the subject works as a sender of signs. ‘Perception and action [operation] are the life-tasks of the animal subject.’ (J. v. Uexküll; above, pp. 70, 74) Even cells are *autonomous subjects. ‘The subject is the new factor of nature which Biology introduces in Natural Science.’ (J. v. Uexküll 1931b: 389)

References (in order of appearance):

(This text)

von Uexküll, Jakob (1931b). Die Rolle des Subjekts in der Biologie. Die Naturwissenschaften 19, 385-391.

]

§27

[Consider an example of how a neutral object can take on various meanings depending on its use. A round glass bowl, when placed in an outer wall, takes on the meaning of a window, but when we put water and flowers in it, it takes on the meaning of a vase.]

Uexküll then gives a couple more examples for how such meaning changes have an influence that “exercises on the properties of the object”. He gives the example of having a round glass bowl. [See this example in Theoretical Biology §§515-517]. Were we to put water in it and use it as a vase, it would have one meaning. But were we to install it as a window in our house to allow light to come in but not make the inside visible to the outside, it would have another meaning (4/28/140).

The influence that the transformation of meaning [change in meaning / Bedeutungswandel] exercises on the properties of the object [Gegenstandes] is clarified by two further examples. I take a domed glass dish, which can serve as a neutral object [simple object / Gegenstand] because it has not performed any previous function for human beings. I insert the glass dish into the outside wall of my house and transform it in this way into a window that lets in the sunlight; but, because it also reflects light, it screens out the glances of the passers-by. However, I can also place the glass dish on a table, fill it with water, and use it as a flower-vase.

(4/28/140, bracketed insertions mine)

§28

[Properties of an object that lend to its main function are called key [leading / leitende] properties, and those that lend to a secondary function of the object are called subsidiary [supporting / begleitende] properties.]

We might think that the properties of the object remain the same regardless of the changes in its meaning. This is so, but what has changed in the different uses of the bowl is that “its various properties acquire a rank-order of importance”: in the case of it being a window, its transparency is its higher ranking property, and its curvature less so; but when it is a vase, its curvature is the key property and its transparency is less important (4/28/140). When the property is the important one, then it is called the “leading property”, but when it serves a lesser important function, then it is a “supporting property”. [For more on this distinction see Theoretical Biology §519].

The properties of this neutral object [object / Gegenstandes] are not altered at all during these transformations. But as soon as the glass dish has been transformed into a meaning-carrier [carrier of meaning / Bedeutungsträger], ‘window’ or ‘vase’, its various properties acquire a rank-order of importance. The transparency of the glass is a ‘key’ property [“leading” property / “leitende” Eigenschaft] of the window, while its curvature represents a subsidiary property [supporting property / begleitende Eigenschaft]. In the case of the vase, the obverse is true: The curvature is the key [leading / leitende] property and the transparency the subsidiary [supporting / begleitende] property.

(4/28/141, bracketed insertions mine)

§29

[Scholastic philosophers distinguished essential and accidental object properties. Since these correspond to key and subsidiary properties, they must have been thinking of objects in terms of meaning-carriers (for otherwise there would be no ranking to the properties).]

Uexküll relates this to the scholastic distinction of essentia and accidentia. This distinction only holds for meaning-carriers, where certain features are essential (or “key”) and others are accidental (or “subsidiary”) (4-5/28/141).

§30

[Another example: consider two long poles connected by a series of smaller poles between them. Stood vertically, it is a ladder. Stood horizontally, it is a fence.]

His other example is a “neutral” object that is made of two long poles that are connected to each other by a series of other poles spanning between them, at regular intervals. If we lean the long poles up against a wall, then it “acquires a ‘ladder-quality’ (Leiter-Ton) [“climbing tone” / “Kletterton”]; but it takes on the quality of a fence when we place the long poles horizontally on the ground (5/28/141, bracketed insertions mine).

§31

[When the pole-structure is used as a fence, the distance between the cross-poles is accidental, because they need not be equally spaced to support the top beam. But when it is serving as a ladder, the equidistance becomes a key property, because it is meaningful for that particular usage.]

When it is acting as a fence, the distance between the cross-poles is accidental [because they could be irregular and it would still serve as a fence], but when it is acting as a ladder, that equidistance becomes key, because that is important for its meaning or use as a ladder (5/28/141).

It soon becomes apparent that, in the case of the fence, the cross-poles play a subordinate role [nebensächliche Rolle]. In the case of the ladder, however, they must be distanced at regular intervals so as to make steps possible. A simple spatial construction-plan [einfacher räumlicher Bauplan] is, therefore, already apparent in the meaning-carrier [carrier of meaning / Bedeutungsträger], ‘ladder’, which makes. the performance of step-climbing possible.

(5/28/141, bracketed insertions mine)

§32

[It is wrong to believe that we can think of human implements simply as relationless objects only by subtracting humans from the picture, like thinking of a normal house but without the people in it.]

Thus it is incorrect to treat the useful things in our world as relationless objects. We see this if we consider a human house with all its items and think of it objectively by removing the humans.

In an imprecise manner of expression, we designate all our useful things [objects / Gebrauchsdinge] (even though they are one and all carriers of human meaning [human meaning-carriers / menschliche Bedeutungsträger]) simply as objects [Gegenstände], as if they were simple, relationless objects [beziehungslose Objekte]. Indeed, we treat a house along with all the things [Dingen] found in it as objectively existent, whereby we leave human beings as dwellers in the house and users of the things [Dinge] completely out of the picture.

(5 / 28 / 141, bracketed insertions mine)

[Note, I did not use the 2010 English edition, because certain terms and structures did not match. See for example the inclusion of “Ton” below, which is not in the 1940 German edition (but perhaps is in some other one).]

It is inaccurate to refer to all the uses to which objects are put (although they are, each and all, human meaning-carriers as if they were neutral, devoid of quality (Ton). We even regard a house, with all the things contained in it, as if it existed ‘objectively’ as a neutral object, in that we totally disregard the people who occupy the house and use the things in it.

(5 / 28 / 141)

§33

[Subtracting humans from the house still keeps the human-centered meanings of the things in the house. This becomes apparent when we think of adding a dog to the human-less house. The dog would not recognize the household objects in the same way.]

But we notice the problem with this when we instead think of a dog living in the house and we consider its relations to the things in the house.

That this view is wrong is demonstrated immediately if we replace the human being with a dog as occupant of the house and envisage its relationships to the things in it.

(5/28/141-142)

§34

[A dog trained to the command ‘chair’ will sit on a human chair, but if one is lacking, it will seek out some other sort of seating that is not fitting for a human.]

[To reinforce his point, Uexküll mentions a phenomenon that can happen when training a dog to learn the command ‘chair’. Apparently it will learn to sit on a human chair, as originally instructed. But when you remove all human chairs from the vicinity, and still command “chair”, it looks for some other sort of thing appropriate for a dog to sit on. In other words, what makes something a chair for the dog is not the properties assigned to it but rather its potential to serve as a thing to sit on, which for a dog can be many other sorts of things that humans would not normally call a chair. I will quote, and note the idea of “being on the look-out”, which Deleuze speaks of with regard to animals and signs in his Abécédaire interviews.]

We know from Sarris’s experiments that a dog trained to the | command ‘chair’ learns to sit on a chair, and will be on the look-out for other seating-accommodations if the chair is removed; indeed, he searches for canine sitting-accommodations, which need in no way be suitable for human use.’

(5/28-29/142)

§35

[The dog chooses other objects for chairs because these other objects have a sitting-quality for dogs, even though they do not have that quality for humans.]

The reason the dog will find other objects it was not trained to sit on is because for the dog, these other objects have the same sitting-quality as the human chair, (even though they do not have that quality for humans).

The various sitting-accommodations all have the same ‘sitting-quality’ (Sitz-Ton) [sitting tone / Sitzton]; they are meaning-carriers [carriers of meaning / Bedeutungsträger] for sitting because they can be exchanged with each other at will, and the dog will make use of them indiscriminately upon hearing the command ‘chair’.

(5 / 29 / 142, bracketed insertions mine)

§36

[The things in the human house may either have the same qualities for the dog, as the staircase has a climbing quality for both, or they make take on different qualities, as the furniture has a sitting-quality for humans but an obstacle-quality for dogs, or they may have no quality, as spoons for example have no use value for dogs.]

Thus with regard to the example of the human house with a dog occupant, all the things will take on different qualities depending on how the dog relates to them (5-6/29/142). For example, a lot of furniture [which has a sitting-quality for humans] will have an “obstacle-quality” for the dog. And “All of the small household effects, such as spoons, forks, matches, etc. do not exist for the dog because they are not meaning-carriers” (6 / 29 / 142).

§37

[Thus it is insufficient to use the dog’s qualities of the household items for a human-centered description.]

Thus it is insufficient for a human inhabitant were the house’s contents to be described simply in terms of the qualities that the dog imparts to them (6/29/142).

§38

[If we think of a forest, we will see that it is inadequate to describe it in human terms.]

[So it is insufficient to describe a human house in dog terms.] We can further gather that if we simply describe a forest in human terms, we will fail to grasp its full meaning.

Are we not taught by this example that the forest, for instance, which the poets praise as the most beautiful place of sojourn for human beings, is in no way grasped in its full meaning if we relate it only to ourselves?

(6 / 29 / 142, bracketed insertions mine)

§39

[For, the things in the woods have a plurality of meanings, depending on what sort of person or which kind of animal is interacting with them.]

This is because the forest has different constituent meanings depending on the sort of person or mode of interaction with it.

Before we follow this thought further, a sentence from the Umwelt chapter of Sombart’s book About the Human may be cited:

No ‘forest’ exists as an objectively prescribed environment. There exists only a forester-, hunter-, botanist-, walker-, nature-enthusiast-, wood gatherer-, berry-picker- and a fairytale-forest in which Hansel and Gretel lose their way.

(6 / 29 / 142, bracketed insertions mine)

§40

[And since there are many animals each relating to the woods in its own way, we can think of there being a vast plurality of different meanings for the same things in the woods.]

And this is even more the case when we consider the different ways that the other animals engage with the things in the woods.

The meaning [Bedeutung] of the forest is multiplied a thousandfold if its relationships are extended to animals, and not only limited to human beings.

(6/29/142, bracketed insertions mine).

§41

[Given the breathtaking number of meaning worlds in one forest, we might simply enjoy our wonderment of them all. However, we should now examine a typical case to see the network relating the many Umwelten.]

[At this point we might be amazed by the idea of all the meaning worlds of each creature overlapping in one forest.] Uexküll says that we should not become “intoxicated with the enormous number of *Umwelts (subjective universes) [Umwelten / environments] that exist in the forest” (6/29/143, bracketed insertions mine). He will instead examine a typical cases to analyze the “relationship-network of the Umwelts [tissue of relationships among the environments / Beziehungsgewebe der Umwelten]” (6/29/143, bracketed insertions mine).

[From the Glossary:

Umwelt (subjective universe, phenomenal world, self-world) (Umwelt) The part of the environment of a *subject that it selects with its species-specific sense organs according to its organization and its biological needs. Everything in the Umwelt is labeled with the *perceptual cues and *effector cues of the subject. ‘Every subject is the constructor of its Umwelt.’ (J. v. Uexküll 1931a: 217)

(87)

Reference:

von Uexküll, Jakob (1931a). Der Organismus und die Umwelt. In Das Lebensproblem im Lichte der modemen Forschung, H. Driesch and H. Woltereck (eds.), 189-224. Leipzig: Quelle und Meyer.

]

§42

[As an example of the same object having different meanings for different animals, and thus as having a different meaning in different Umwelten, we consider a flower-stem in a meadow. {1} A girl uses the stem to affix the flowers on herself as decorations. {2} An ant uses the stem as a path to climb to its food source at the petals. {3} A cicada-larva bores into the stem to obtain sap it needs to construct a living structure. And {4} a cow eats both the stem and flower as food.]

Uexküll has us consider a flower blooming in the meadow, and in particular we are to think of the flower’s stem. [It is a part of many Umwelten, as many as there are different creatures in the meadow that relate to it in their own way.] We will limit our attention to just four Umwelten, and we will note the role the flower stem plays in each:

{1} the role it plays “In the Umwelt of a girl picking flowers, who gathers herself a bunch of colorful flowers that she uses to adorn her bodice” (6/29/143);

{2} the role it plays “In the Umwelt of an ant, which uses the regular design of the stem- | surface as the ideal path in order to reach its food-area in the flower-petals” (6/29-30/143);

{3} the role it plays “In the Umwelt of a cicada-larva, which bores into the sap-paths of the stem and uses it to extract the sap in order to construct the liquid walls of its airy house” (6/30/143); and

{4} the role it plays “In the Umwelt of a cow, which grasps the stems and the flowers in order to push them into its wide mouth and utilizes them as fodder” (6/30/143).

§43

[Thus the flower plays the following roles corresponding to its Umwelt-stage (Umweltbühne): {1} ornament, {2} path, {3} spigot, and {4} food.]

There is a different “Umwelt-stage” (Umweltbühne) for each usage. [Perhaps we may think of it as like the same theatrical scene being staged in different ways to bring out different perspectives or meanings.] Thus for the four creatures above, the flower stem serves the following roles in each respective Umwelt: {1} ornament for the girl, {2} path for the ant, {3} spigot for the cicada-larva, and {4} food clump for the cow.]

According to the Umwelt-stage [(missing) / Umweltbühne], on which it appears, the identical flower stem at times plays the role of an ornament, sometimes the role of a path, sometimes the role of an extraction-point, and finally the role of a morsel of food.

(6 / 30 / 143, bracketed insertions mine).

§44

[The flower-stem has a design suited to diverse multiple functions. It is thus far superior in design to human-made machines, which are much more limited in functionality.]

[I am not certain of the next point. Uexküll might be noting that human machines often are designed for and normally serve one or a limited range of functions, but the flower stem serves many functions. Insofar as a mechanism is defined as an object serving functions, we might say that the stem is a far more sophisticated mechanism than any human-made machine. Also, Uexküll characterizes the stem as consisting of “well-planned interwoven components [planmäßig ineinander gefügten Komponenten]” (6-7 / 30 / 143, bracketed insertions mine). This idea of ‘plan’ is important, but difficult at the same time. My own knowledge of it is so far limited to the ideas from section 4.6 of Theoretical Biology. We begin with the notion of a human tool having certain meaningful relations between its parts, which are ordered as such to serve its particular function. So the ladder has a design or plan calling for there to be two long vertical parts and a series of evenly spaced horizontal ones. It does not matter so much the material being used, so long as it supports enough weight. We then broaden this notion to the life forms in nature. They each can be said to have anatomical structures (and behavioral patterns) with functional purposes that thus seemingly accord with a “plan” or design. We furthermore see how all animal’s have their own plans or designs which place them into reciprocal relations with the plans or designs of other animals (we see this with symbiotic relations but also even with predator-prey relations, where the abilities or strategies of one creature are countered by those of another creature.) These sorts of intertwinings of creatures give us the sense that they all fit within an even larger plan of nature. And given that the materials in the inorganic world have certain specific properties that lend to life, we might even see a plan arching over all of the world, both organic or inorganic.]

This is very astonishing. The stem itself, as part of a living plant, consists of well-planned interwoven components [components connected to one another according to a plan / planmäßig ineinander gefügten | Komponenten] that represent a better-developed mechanism than any human machine.

(6-7/30/143, bracketed insertions mine)

§45

[The components of the stem are given different structuralizations depending on the functional use it has for the particular animal giving meaning to it. Also, there will be a part of the animal’s body corresponding to the stem; it will be the part that interacts with the stem.]

[Uexküll’s next point continues with the notion of plan, but this time with “building-plan”. As I am unsure I understand it well, please consult the quotation below. Uexküll might be saying the following. The stem has certain components, both structural in nature and material in nature. These parts can take on different building-plans, depending on who is relating to the stem. Perhaps we might say that for the stem itself, the stem means a number of things, given its functions, which are supported by its structures. So the stem props up the blossom, which is its means of reproduction. So it is structured to support weight and to rise up off the ground. It also channels water and sap. So perhaps from the perspective of the flower (supposing we can consider it from a plant’s perspective), the stem’s building-plan is its particular arrangement of cells of certain types so that it channels water and supports weight. For the girl, the stem is what pokes into her garments. So for her, the stem’s building-plan is simply the structural features making it firm, but it does not include those features allowing water to rise through it. For the ant, the building-plan might be simply those structural features that allow its feet to climb it and also that allow there to be petals at the top end of it. For the cicada-larva, the building-plan is perhaps the structural features that allow the sap to flow through the stem, and also maybe the features making the stem somewhat woody. For, the larva is anatomically suited to bore into things with such a feature. And for the cow, the building-plan is perhaps the chemical make-up of the stem, which provides nourishment to the cow, but also its particular structural features that enable it to be chewed. Uexküll’s next idea seems to be the following. Consider the anatomy of the larva, which is “designed” so to speak to bore into the stem. Or recall how the cow’s teeth and stomach are “designed” to eat and digest the flower. From this, we might gather the following idea. Consider any living or non-living object that appears in an animal’s Umwelt. This means that it relates to that animal in some functional way. That furthermore means that the animal somehow interacts with it. That even further means that there is some part of the animal that interacts with the object (or some part of it, at least), like a “complement” to it. Let me quote:]

The same components that are subjected to a certain building-plan (Bauplan) [construction plan / Bauplan] in the flower stem are torn asunder into four different Umwelts [environments / Umwelten] and are integrated, with the same certainty, into various new building-plans (Baupläne) [construction plans / Bauplänen]. Each component of an organic or inorganic object, on appearing in the role of a meaning-carrier [carrier of meaning / Bedeutungsträgers] on the life-stage [stage of live / Lebensbühne] of an animal subject [Tiersubjectes], has been brought into contact with a ‘complement’, so to speak, in the body of the subject that becomes the *meaning-utilizer [consumer of meaning / Bedeutungsverwerter].

(7/30/143, bracketed insertions mine)

[From the Glossary:

Meaning-utilizer (Bedeutungsverwerter) A *subject or a part of a subject’s body that is brought into contact with a *meaning-carrier. ‘Each component of an organic or inorganic object, on appearing in the role of a meaning-carrier on the life-stage of an animal subject, has been brought into contact with a ‘complement’, so to speak, in the body of the subject that becomes the meaning-utilizer.’ (J. v. Uexküll; above, p. 30)

References:

(This text)

]

§46

[But, given the invariability of the body’s plan and variability of the Umwelt’s plan, there seems to be a contradiction between these types of plans.]

[I do not grasp the next point, so please consult the quotation. I will guess it conveys the following ideas. The animal body has fixed functional parts to it, and these parts relate to the things in its Umwelt. However, the things in its Umwelt do not have fixed relations between their parts, because they vary depending on which animal is relating to it. Because the things in the Umwelt can structurally vary, that makes it incomplete as a system, at least in comparison to the animal’s body; for, the Umwelt is always open to other arrangements, but the animal’s body is not. (By the way, I would think that even the animal’s body has a structure that varies, but here according to which other creature is using its body. For example, the fat in its body might function to give it warmth, but to another creature who eats this first animal, the fat might function to give nourishment.) What this suggests, somehow, is that there is an apparent contradiction in nature. For, I am guessing, the plan of the body would have one sort of structure, (namely a fixed one) while the plan of the Umwelt will have a different sort of structure (namely a variable one). Please check the quotation.]

This conclusion draws our attention to an apparent contradiction in the fundamental features of living nature. The fact that the body structure is ordered according to a plan (Planmässigkeit) [the planned quality of the body structure / Planmäßigkeit des Körpergefüges] seems to contradict the idea that the Umwelt structure is also ordered according to a plan (Planmässigkeit) [the planned quality of the environmental structure / Planmäßigkeit des Umweltgefüges].

(7/30/143, bracketed insertions mine)

§47

[The variability of the Umwelt’s structure might make us think it is less systematically complete than the animal’s body, but this is an illusion.]

[The things in the Umwelt can vary in their structuralization depending on which animal is giving it which functional meaning. But the structuralization of the animal in the Umwelt remains fixed (for that animal at least). This makes the Umwelt seem like an incomplete system in comparison with the animal’s body. But this is an illusion.]

One must not be under the illusion that the plan to which the Umwelt structure [environment structure / Planmäßigkeit des Umweltgefüges] accords is less systematically complete than the plan according to which the body structure [bodily structure / Planmäßigkeit des Körpergefüges] is ordered.

(7 / 30 / 143-144, bracketed insertions mine)

§48

[But an Umwelt is for its creature an enclosed unit, being of limited space and contents.]

[I am not certain, but these seem to be the next points. We recall the idea that the Umwelt is not a “complete” system, because its parts can vary in structure. However, this is perhaps to look at an Umwelt from the outside. An Umwelt is a subjective world. From the perspective of the subject, the Umwelt is a closed unit or system, because its parts do not vary in meanings for itself in the way they vary with respect to the many other different animals in the vicinity. The limitedness of that world is not just with the meaning-structures the things bear. It is also a spatial matter. The animal’s sense organs and perceptual apparatus produce space around the animal that is limited both in scope and in internal division into specific localities. (See Theoretical Biology section 3.2 on the spatial “bubble” surrounding the animal.)]

Each Umwelt [environment] forms a closed unit in itself, which is governed, in all its parts, by the meaning it has for the subject. According to its meaning for the animal, the stage on which it plays its life-roles (Lebensbühne) [life-stage] embraces a wider or narrower space. This space is built up by the animal’s sense organs, upon whose powers of resolution will depend the size and number of its *localities (Orte). The girl’s field of vision resembles ours, the cow’s field of vision extends away over its grazing-area, while the diameter of the ant’s field of vision does not exceed 50 centimeters and the cicada’s only a few centimeters.

(7 / 30 / 144, bracketed insertions mine)

[From the Glossary:

Locus (place, locality) (Ort) The smallest element of space; it is a projected *local sign and as such a *perceptual cue for *objects of the motor activity of subjects.

(84)]

§49

[The space is distributed differently for each animal Umwelt.]

The places in space have a different distribution in each Umwelt, since every creature lives in a different scale and finds certain sorts or things and surfaces significant.

The localities [Orte] are distributed differently in each space: The fine pavement the ant feels while crawling up the flower stem does not exist for the girl’s hands and certainly not for the cow’s mouth.

(7 / 30 / 144, bracketed insertions mine)

§50

[Different parts or features of the object will be important for some creatures but not for others.]

The structures and chemistry of the flower stem are not important for the girl or ant, but they are for the cow, who must digest the material (7 / 30-31 / 144).

§51

[The Umwelt will be divided into things according to the functional structures that interest that Umwelt’s animal.]

[The next points seem to be the following, but please consult the quotation. All the things in an animal’s Umwelt have some meaning or other. If there is some component that is not important to that animal, then it is not really in the Umwelt, since only meaningful structures are. (Or perhaps we should say that objects without meaning in an Umwelt are really grouped with meaningful objects neighboring them, and so with everything belonging to one meaningful object or another, there is nothing left out.) We noted before that the spoon might be in the house, but it does not have any functional meaning for the dog. As such, it perhaps simply melds with whatever is around it, like it is part of a pile of useless shiny junk. Or, things that previously had no particular structure can gain them. I am not sure what would be a good example with the dog. But perhaps there are things maybe in the garbage that it distinguishes by smell, but that humans would have just lumped together as one pile of refuse.]

Everything that falls under the spell of an Umwelt (subjective universe) [environment] is altered and reshaped until it has become a useful meaning-carrier [carrier of meaning / Bedeutungsträger]; otherwise it is totally neglected. In this way the original components are torn apart without any regard to the building-plan [structural plan / Bauplan] that governed them until that moment.

(7-8 / 31 / 144, bracketed insertions mine)

§52

[Although the functional structure of an object varies for each Umwelt, it retains the same interactive structure, in which there are two parts, the perceptual cue-carriers (carriers of perception marks / Merkmalträger) and the effector cue-carriers (carriers of effect marks / Wirkmalträger)]

[I am not sure I follow the wording in the next paragraph. Let me quote it first.]

The contents of the meaning-carriers are different in the various Umwelts, although they remain identical in their structures. Part of their properties serve the subject at all times as *perceptual cue-carriers, another part as *effector cue-carriers.

(8 / 31 / 144)

As different as the carriers of meaning are in their respective environments according to their contents, they are just as completely similar in their structure. Part of their qualties serves the subject as carriers of perception marks, another part as carriers of effect marks.

(8 / 31 / 144)

So verschieden die Bedeutungsträger in den verschiedenen Umwelten ihrem Inhalte nach sind, so völlig gleichen sie sich in ihrer Bauart. Ein Teil ihrer Eigenschaften dient stets dem Subjekt als Merkmalträger, ein anderer als Wirkmalträger.

(8 / 31 / 144)

[I was confused, because one interpretation of the first sentence could be that that the same thing, like the flower stem for example, will have the same contents in the four different Umwelten but different structures. That would seem to be the opposite of what was said before, where the same thing has different structures but is composed of the same material. Given what is said then in the following sentence, I gather the structure here is not the same structure we mentioned before, namely, the functional structure, but is now a different sort of structure, in this case, the perceptual-effectual structure. So I will guess that he is saying that while the functional structure will vary per Umwelt, the general two-part interactive structure will remain the same.]

[From the Glossary:

Perceptual cue (Merkmal) A projected *perceptual sign appearing as a property of the *object that releases a specific *operation.

(86)

Effector cue (operational cue) (Wirkmal) A projected *impulse to action (operation). The change of the *perceptual cue as an effect of the action (operation) establishes the feedback loop of the *functional circle.

(84)]

§53

[Different features of the same thing can serve as different perceptual cues for different animals.]

In each Umwelt, the flower stem has features that the creature perceives and finds significant. For example, the girl selects the flowers for decoration, so the color of the blossom serves as a cue to its suitability for that purpose. The cicada larva uses smell to find where to bore into the stem [so presumably the stem has parts to it with a certain smell that serve as perceptual cues for where to bore.]

The color of the blossom serves as an optical perceptual cue [optical perception mark / optisches Merkmal] in the girl’s Umwelt [environment], the ridged surface of the stem as a feeling perceptual cue [tactile perception mark / Tastmerkmal] in the Umwelt [environment] of the ant. The extraction-point presumably makes itself known to the cicada as a smell perceptual cue [olfactory perception mark / Geruchsmerkmal]. And in the cow’s Umwelt [environment], the sap from the stem serves as a taste perceptual cue [taste perception sign / Geschmacksmerkmal].

(8 / 31 / 144-145, bracketed insertions mine)

§54

[There will be some part or feature of the object that the animal will work upon and create an alteration to. There will be the location of the effect mark.]

[I might not have the next point right. It may be that there are certain features of the object that will receive the effect marks. For example, on the flower stem, there will be a weak part along it. When the girl pulls on the flower, that weak part is where the break happens. It receives the effect mark, because it is there that the change is shown. Another possibility is that the effector cue is not necessarily the mark of the effect of the animal’s action, but rather it is the feature that the animal acts on specifically. So perhaps the girl feels for the weak part, and pulls at that point.]

The effector cues [effect marks / Wirkmale] are mostly imprinted upon other properties of the meaning-carrier [carrier of meaning / Bedeutungsträgers] by the subject: The thinnest point of the stem is torn apart by the girl as she picks the flower.

(8 / 31 / 145, bracketed insertions mine)

§55

[For the ant walking on the stem, the unevenness of the surface is something it is feeling for, and is thus a perceptual cue, but it is also moving its feat in accordance with that unevenness, and thus it is as well an effector cue.]

[In the next illustration, we are to think of the stem having an unevenness to it. The ant uses its feelers to detect the places (presumably uneven parts of the stem) where it will put its feet. So that unevenness of the surface serves both as the perceptual cue, because it is what the animal is perceiving as significant for its actions. And, it is the effector cue, because it applies its action also to those same uneven places it detected. Or, if an effector cue is the mark left from the result of the action, then perhaps the steps of the ant leave some sort of chemical trail or some other change in the surface.]

The unevenness of the stem’s surface serves the ant both as a touch perceptual cue [tactile perception mark / Tastmerkmals] for its feelers and as an effector cue-carrier [carrier of the effect mark / Wirkmalträger] for its feet.

(8 / 31 / 145, bracketed insertions mine)

§56

[The cicada uses smell to find the extraction-point.]

As we noted, the cicada uses smell to find a suitable place to bore into and extract sap for its house building material (8 / 31 / 145).

§57

[The taste of the stem tells the cow to eat more flowers.]

And the taste of the stem tells the cow to eat more flowers [because the taste indicates to the cow that they are nourishing] (8 / 31 / 145).

§58

[The effector cue assigns a new meaning to the object that the animal is reacting to. This extinguishes the perceptual cue that originally spurred the effective action, because that cue no longer is significant after the effective action has been completed.]

[The next idea is very tricky, and I do not have it all clearly in my mind yet. I will guess it to be the following. Consider the ant walking up the stem. The perceptual cue tells it how to move up the stem. Prior to it walking up the stem, the stem was just a part of the Umwelt and not appropriated meaningfully as something related to the ant itself. It is like a potential path for the ant. But only when the ant actually walks upon the stem has it left its mark on it and designated it as a path. So we can see how the effective action leaves its mark on the world and in that sense endows it with certain functional meanings. But we also need to see how the effector cue extinguishes the perceptual cue. One possibility is that after it has served its function, it no longer becomes interesting, and thus its features that would normally spur a certain action no longer do so (consider for example how we notice the smell of food easily when we are hungry but then would rather not smell it after we eat a lot). This was the sort of interpretation we gathered from Stroll through the Worlds of Animals and Men (see the Introduction, §§39 and 43). The other possibility is that the actual feature itself is destroyed or altered, like the cow eating the stem. At any rate, there are two possible senses for “extinguish” when the effector cue extinguishes the perceptual cue: {1} it puts the perceptual cue out of relevance and concern, “dephenomenalizing” in the sense that while it might still be sensed, it does not take the animal’s interest, and {2} the effector cue destroys or alters the perceptual cue by effectively transforming the feature. I am inclined to go with the first meaning, which could be found in the second, because were the feature destroyed, that would also make it no longer perceptible anyway.]

Because the effector cue [effect mark / Wirkmal] that is assigned to the meaning-carrier [carrier of meaning / Bedeutungsträger] extinguishes in every case the perceptual cue [perception sign / Merkmal] that caused the operation, each *behavior is ended, no matter how varied it may be.

(8 / 31 / 145, bracketed insertions mine. Note the translation of Merkmal as perception sign. I am used to seeing “Merkzeichen” translated as perception sign, and it is something different from the perception cue.)

[From the Glossary:

Behavior (Verhalten) The activities of living beings as they appear to the observer.

(83)]

§59

[A creature’s effective actions transform the object into something with particular meaning in that creature’s Umwelt, like how the cow transforms the flower into food by eating it.]

The effective action of the creature transforms the object into something with a new meaning for that creature. For example, by picking the flower, the girl transforms it into an ornamental object. By walking up the stem, the ant transforms it into a path (8 / 31 / 145). By eating the flower, the cow transforms the stem into food.

§60

[Actions have two parts: {1} a perceptual part that detects features which trigger effective actions, and {2} an effectual part that transforms the otherwise meaningless object into a meaning-carrier related to the animal subject, and it does this by imprinting a meaning onto that object.]

So action has two parts to it, a perceptual and an effectual. The effectual imprints a meaning onto an otherwise meaningless object.

Every action, therefore, that consists of perception and operation imprints its meaning on the meaningless object and thereby makes it into a subject-related meaning-carrier in the respective Umwelt (subjective universe).

(9 / 31 / 145)

In this way, every action impresses its meaning on a meaningless object and makes it thereby into a subject-related carrier of meaning in each respective environment.

(9 / 31 / 145)

So prägt jede Handlung, die aus Merken und Wirken besteht, dem bedeutungslosen Objekt ihre Bedeutung auf und macht es dadurch zum subjektbezogenen Bedeutungsträger in der jeweiligen Umwelt.

(9 / 31 / 145)

§61

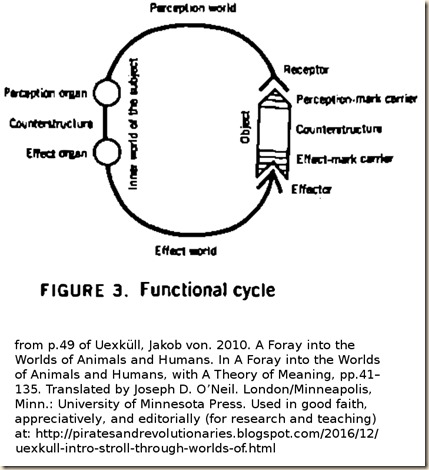

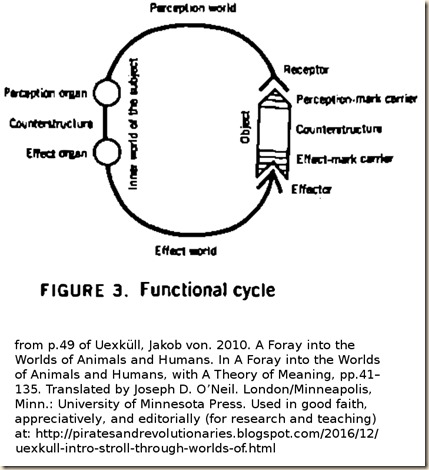

[The meaning-carrier cues an action from the subject by means of perception, then the subject commits an action which transforms the meaning-carrier. This then is a functional circle.]

Uexküll then places these ideas into his functional circle schema. [We discuss it in greater detail in Stroll through the Worlds of Animals and Men, Introduction, §42.]

Because every behavior begins by creating a perceptual cue and ends by printing an effector cue on the same meaning-carrier, one may speak of a *functional circle that connects the meaning-carrier with the subject (Figure 1).

(9 / 31 / 145)

Since every action begins with the production of a perception mark and ends with the impression of an effect mark on the same carrier of meaning, one can speak of a functional cycle, which connects the carrier of meaning with the subject.

(9 / 31 / 145)

Da jede Handlung mit der Erzeugung eines Merkmals beginnt und mit Prägug eines Wirkmals am gleichen Bedeutungsträger endet, kann man von einem Funktionskreis sprechen, der den Bedeutungsträger mit dem Subjekt verbindet .

(9 / 31 / 145)

[From the Glossary:

Functional circle (Funktionskreis) The cyclic connection between parts of the *environment of a living being, its *perception, and its behavioral answer (or *operation). A methodological tool to investigate and reconstruct its *Umwelt. There are four main circles: *medium, food, enemy, and sex.

(84)]

§62

[The most important functional circles are of the physical medium, food, enemy, and sex.]

There are four primary functional circles, namely, those of the physical medium, food, enemy, and sex (9 / 33 / 145).

§63

[Because of their functional interaction, the meaning-carrier (the significant object with which the subject is interacting) becomes a complement to the subject. Some of its properties are leading, while others are subsidiary. The features of the object which serve neither as perceptual nor as effector cues (and as well the overall coherence of the whole object in terms of its various properties) is the objective connection structure (Gegengefüge), because it (structurally) connects the perceptual and effector meaning-carriers.]

So we understand the object as a meaning-carrier, because it has entered into the animal’s functional circle, which causes it to have some significance in the animal’s functioning. Thus [while it may have begun as a relationless, neutral object] the meaning-carrier becomes a complement of the animal subject. [It in a sense has linked up with it.] [Now, the meaning-carrier has a variety of properties.] Some of the meaning-carrier’s properties play a leading role either as a perceptual cue-carrier or as an effector cue-carrier. However, other properties may simply play a subsidiary role as a cue-carrier. [I am not sure how that would work, unless the object has multiple functions, with certain properties indicating primary functions and others indicating secondary functions. We examined the case of the glass bowl. Suppose we were selecting a glass vessel for drinking wine, where both options before us have the same suitable shape, but one is transparent and the other is not. Our primary aim is to drink the wine. So the shape is the leading indication for both. But since it would be better, although not necessary, to inspect the color of the wine as well, the transparency of the transparent one would serve as a subsidiary indication. I am guessing.] [There is another important but tricky part of the meaning-carrier’s structure. It does not just have a perceptual cue-carrier and an effector cue-carrier. It also has a connecting structure that links them together. In Stroll through the Worlds of Animals and Men, Introduction, §42, we tried to elaborate on this concept. It is still very unclear to me. Let me consider some possibilities. The previous interpretation we gave it was that there are certain properties in the object that are related such that a change in one results in a change in the other. Here also we interpreted the effector cue-carrier as the causal result of the interaction. So in the tick example we examined, the animal skin had relations between its parts such that the bite to the skin resulted in changes in the skin’s appearance. But now we are considering the possibility that the effector cue-carrier is not the causal result of the animal’s action but rather an indication of where on the meaning-carrier specifically to interact. In that case the objective connecting structure is less obvious. In the case of the ant feeling the places to put its feet, they are spatially connected. But for the girl picking the flower, the color of the petals was the perceptual cue-carrier while the weak part in the stem was the effector cue-carrier. What then would be the objective connecting structure? Is it simply the physical connections from the petals down to that weak part of the stem? There was also the example of the bee and honey in Theoretical Biology, section 3.6, §394d (which was not in the German second edition). Here, the smell of the honey was perhaps a perceptual cue-carrier, and the fluidity was perhaps an effector cue-carrier (at that time, those terms were not used, but rather these properties we divided into world-as-sensed and world of action.) The smell acted on the bee, but the fluidity is what allowed the bee to take action, namely, to drink the honey. But here again it is not clear what the objective structure would be, besides the fact that the same material which has a certain smell also has a certain degree of fluidity. I will quote.]

Due to its integration into a functional circle, every meaning-carrier becomes a complement of the animal subject. In the process, particular properties of the meaning-carrier play a leading role as perceptual cue-carriers or effector cue-carriers; and other properties, on the other hand, play only a subsidiary role. The biggest part of the body of a meaning-carrier frequently serves as an undifferentiated *objective connecting structure (Gegengefüge) whose function is only to connect the perpetual cue-carrying parts with the effector cue-carrying parts.

(9 / 33 / 145-146)

[From the Glossary:

Objective connecting structure (Gegengefüge) The material connection between carriers of *perceptual cues and carriers of *effector cues. This connection exists only in the *Umwelt of the observer and remains outside the Umwelt of the observed animal.

(85)]

Thanks to its insertion in a functional cycle, every car- | rier of meaning becomes the complement of the animal subject. Thereby, some individual properties play a leading role as carriers of perception marks or of effect marks, while others only play a supporting role. Frequently, the greatest part of the body of a carrier of meaning only serves as an undifferentiated counterstructure, which is only there in order to hook up the perception sign-carrying parts with the effect sign-carrying ones (compare Figure 3).

(9 / 33 / 145-146)

Dank seiner Einfügung in einen Funktionskreis wird jeder Bedeutungsträger zum Komplement des Tiersubjekts. Dabei spielen einzelne Eigenschaften als Merkmalträger oder Wirkmalträger eine leitende, andere Eigenschaften dagegen nur eine begleitende Rolle. Häufg dient der größte Teil des Körpers eines Bedeutungsträgers als ein undifferenziertes Gegengefüge, das nur dazu da ist, um die merkmaltragenden Teile mit wirkmaltragenden aneinander zu knüpfen.

(9 / 33 / 145-146)

Works cited (in this order):

Uexküll, Jakob von. 1940. Bedeutungslehre. Leipzig: Barth.

Uexküll, Jakob von. 1982. The Theory of Meaning. In Semiotica: Journal of the International Association for Semiotic Studies, 42(1), pp.25–82. Translated by Barry Stone and Herbert Wiener.

Uexküll, Jakob von. 2010. A Theory of Meaning. In A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, with A Theory of Meaning, pp.139-208. Translated by Joseph D. O’Neil. London/Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press.

For quotations from the Glossary

Uexküll, Thure von.1982. “Glossary.” In Uexküll, Jakob von. 1982. The Theory of Meaning. In Semiotica: Journal of the International Association for Semiotic Studies, 42(1), pp.25–82. Translated by Barry Stone and Herbert Wiener.